Gennaro Zezza has shared a 1987 paper by him and Wynne Godley modeling the Italian economy using a “real stock flow monetary model”

Tag Archives: wynne godley

Alan Shipman: Wynne Godley, A Biography ‼️

Alan Shipman has written a biography of Wynne Godley!

Links:

Description:

This timely biography of the economist Wynne Godley (1926-2010) charts his long and often crisis-blown route to a new way of understanding whole economies. It shows how early frustrations as a policy-maker enabled him to glimpse the cliff-edges other macro-modellers missed, and re-arm ‘Keynesian’ theory against the orthodoxy that had tried to absorb it. Godley gained notoriety for his economic commentaries – foreseeing the malaise of the 1970s, the Reagan-Thatcher slump, the unsustainable 1980s and 1990s booms, and the crises in the Eurozone and world economies after 2008. This foresight arose from a series of advances in his understanding of national accounting, price-setting, the role of modern finance, and the use of economic data, especially to grasp the interlinkage of stocks and flows. This biography also gives due attention to Godley’s life outside academic economics – including his chaotic childhood, truncated career as a professional oboist, equally brief stints as a sculptor’s model and economist in industry, and a longer spell as as a Treasury adviser with a mystery gift for forecasting.

This first full-length biography traces Wynne Godley’s long career from professional musician to public servant, policymaker, tormentor of conventional macroeconomics and creator of a workable alternative – all after escaping a childhood of decaying mansions and draconian schools, and rescuing his private world from the legacy of two Freuds. Drawing on Godley’s published and unpublished work and extensive interviews with those who knew him, the author explores Godley’s improbable life and explains the lasting significance of his work.

Chapters:

- Life Before Economics

- Under Treasury Rules 1956–1964

- Short-Term Forecasting

- Public Expenditure

- Planning, Tax Reform and Structural Change

- Gatecrashing the Cambridge Tradition

- Public Expenditure Revisited

- Sector Balances and ‘New Cambridge’

- Balance of Payments, Deindustrialisation and Protection

- Spectating on Thatcher and Major

- ‘Macroeconomics’

- The Research Council Showdown

- Wilderness and Wisdom

- Cassandra Across the Atlantic

- The Long Road to Redemption

- Monetary Economics and After

- The True Self

Gerald Epstein’s Critique Of Neochartalism

Gerald Epstein of PERI has written a fine paper The Institutional, Empirical and Policy Limits of ‘Modern Money Theory’ critiquing the shortcoming of Neochartalism.

Epstein’s main critique is that Neochartalism ignores the role of international financial markets and the constraint it puts on fiscal policy. Abstract:

Modern Money Theory (MMT) economists acknowledge a number of empirical and institutional limitations on the applicability of MMT to macroeconomic policy, but they have not attempted to explore these empirically nor have they adequately addressed their implications for MMT’s main macroeconomic policy proposals. This paper identifies some of these important limitations, including those stemming from modern international financial markets, and argues that they are much more binding on the policy applicability of MMT than many of MMT’s advocates appear to recognize. To address these limitations, MMT analysts would have to enter the messy institutional, policy and empirical realms that undermine their simplistic policy conclusions that might be appealing to some policy-oriented followers of MMT. My conclusion is that, in light of these limitations, MMT’s major macroeconomic policy suggestions are of little practical relevance today for progressive politicians and activists, much less to macroeconomic policy formulation in general.

In addition, Epstein has a blog post, Is MMT “America First” Economics?, at INET, which is a short summary of his paper. Excerpt:

To start, even though MMT advocates claim that its macroeconomic framework applies to all countries with “sovereign currencies,” there is significant evidence that it does not apply to the vast majority of such countries in the developing world that are integrated into global financial markets. As is well-known, these countries are subject to the vagaries of international capital flows, sometimes called “sudden-stops.” The problem is that in light of these flows, these countries have limited fiscal and monetary policy space, surely insufficient to conduct MMT-prescribed monetary and fiscal policies for full employment. Wray argues that that flexible exchange rates are sufficient to provide sufficient policy space for these countries to undertake MMT macro-policies. Occasionally the issue of capital controls is briefly mentioned but not seriously discussed as a complementary policy. But a careful survey of the empirical evidence casts grave doubts on the effectiveness of flexible rates for giving policy autonomy or insulating these countries from the vagaries of global financial flows. This problem is worse for countries that cannot borrow in their own currencies, but also applies to small, open countries that are able to borrow in their own currencies. The upshot is that only countries that issue their own internationally accepted currency might have the policy space to conduct MMT policies.

Even for those countries that issue their own international currencies, the sustainability and “exploitability” of the international role is not absolute. The country that has the greatest fiscal and monetary space is the United States, which issues the predominant key currency, the US dollar. Whereas Wray has written that the predominance of the dollar is not something we will need to worry about in our lifetime, historical and empirical evidence suggests that even considerable forces for persistence of key currency positions can weaken over time, perhaps even rapidly and dramatically …

A note

It’s usually assumed that fiscal sustainability is the condition on the rate of interest, r, and the rate of growth, g. However Wynne Godley showed that it is neither necessary or sufficient. You can read more here from my blog.

Wynne Godley And Alex Izurieta — One-Club Golf Is For Losers

Here’s a fantastic 2003 article in The Guardian by Wynne Godley and Alex Izurieta, one among many predicting the economic and financial crisis which started in 2007.

h/t Jo Michell.

Excerpt:

In fact the new regime is not working. After years of euphoric growth, the world has become locked into a stagnation which gets worse by the day. Large imbalances, particularly in trade and in personal debt, have been allowed to develop in the US and Britain which mean that the growth we have is unsustainable. Given the existing policy regime, medium term prospects begin to look frightening.

The US is already in a growth recession because private investment has fallen while a record balance of payments deficit has been bleeding the circular flow of income on an increasing scale. These negative forces have been partly offset by an unsustainable splurge in household borrowing, a consequence of the fall in interest rates and the boom in house prices, in the absence of any control over credit expansion.

The reference to golf is from British politics from 1989. Go to “Column 750” in the link.

Trinity Colleagues Pay Tribute To Robert Neild, 1924-2018

Hashem Pesaran, Partha Dasgupta and Gregory Winter remember Robert Neild.

Dasgupta:

Robert Neild was the last surviving member of a triumvirate that shaped the intellectual climate of economics at Cambridge in the 1970s. That influence lasted for over two decades. Together with Brian Reddaway (Professor of Political Economy) and Wynne Godley (Director of the Department of Applied Economics), Robert encouraged an approach to economics that was in sharp contrast to the then growing attention given in the leading university departments of economics in the UK and USA to economic theory and econometrics. The latter approach drew on mathematical techniques not only because they enabled one to reach conclusions with clarity, but also because they allowed one to trace those conclusions to the underlying hypotheses and data on which the studies were based. In modern economics policy is often kept at a distance. In contrast, the approach that Robert favoured insisted on a tight and constant link between analysis and policy; so much so that the separation between analysis and policy was wafer-thin.

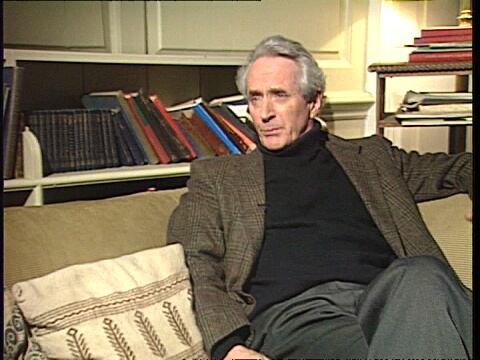

Rare Wynne Godley Video Clips

You might be aware of the hour-long Wynne Godley’s interview with Alan Mcfarlane from 2008 titled, Interview On The Life And Work Of Wynne Godley. But there’s a 90-second clip and a 19-second clip I found from 1993 on Getty Images with the descriptions:

Budget discussions

Budget discussions; INT CMS Prof Wynne Godley (Cambridge University) CMS Prof David Currie (London Business School) Cambridge CMS Prof Wynne Godley (Cambridge University) intvw SOF – Doubtful whether economic turn around will take place as too many people do not have the money/ unemployment is rising and the devaluation will bring about increase in prices/ the ’81 recovery was a dead end/ it was a consumer boom that ended in disaster London CMS Prof David Currie (London Business School) intvw SOF – Can be sure that output will increase but will not feel like a recovery/ unemployment will continue to rise/ ‘Feel Good’ factor could take a year to find its place

and

Budget discussions

Budget discussions; Cambridge CMS Prof Wynne Godley (Cambridge University) intvw SOF – It would take 2-3 percent growth to bring down unemploment [sic] and Govt state it will be one percent

Enjoy!

IMF Paper On How Export Sophistication Is The Determinant Of Growth

Missed this working paper Sharp Instrument: A Stab At Identifying The Causes Of Economic Growth from May 2018 from three IMF authors with an impressive conclusion.

From the abstract

We find that export sophistication is the only robust determinant of growth among standard growth determinants such as human capital, trade, financial development, and institutions. Our results suggest that other growth determinants may be important to the extent they help improve export sophistication.

Note, not only is it saying that it is robust but that other factors are important as long as they improve export sophistication.

Cambridge Keynesians were clear on this. Here’s Wynne Godley in a 1993 article Time, Increasing Returns And Institutions In Macroeconomics, in Market And Institutions In Economic Development: Essays In Honour Of Paolo Sylos Labini, page 79:

… In the long period it will be the success or failure of corporations, with or without active help from governments, to compete in world markets which will govern the rise and fall of nations.

and Nicholas Kaldor in Causes Of Growth And Stagnation In The World Economy, first published in 1996 and based on lectures given in 1984:

The growth of a country’s exports thus appears to be the most important factor in determining its rate of progress, and this depends on the outcome of the efforts of its producers to seek out potential markets and to adapt their product structure accordingly. The income elasticity of foreign countries for a particular country’s products is mainly determined by the innovative ability and the adaptive capacity of its manufacturers. In the industrially developed countries, high income elasticities for exports and low income elasticities for imports frequently go together, and they both reflect successful leadership in product development. Technical progress is a continuous process and it largely takes the form of the development and marketing of new products which provide a new and preferable way of satisfying some existing want. Such new products, if successful, gradually replace previously existing products which serve the same needs, and in the course of this process of replacement, the demand for the new product increases out of all proportion to the general increase in demand resulting from economic growth itself. Hence the most successful exporters are able to achieve increasing penetration, both in foreign markets and in home markets, because their products go to replace existing products.

[italics: mine]

The IMF paper is surprising, since the IMF believes in free trade in which market mechanisms work to achieve convergence in fortunes of nations, so exports is hardly important.

Euro Area Balance Of Payments, Again!

… But more disturbing still is the notion that with a common currency the ‘balance or payments problem’ is eliminated and therefore that individual countries are relieved of the need to pay for their imports with exports.

Quite the reverse: the existence or a common currency makes a country more directly dependent on its ability to sell exports and import substitutes than it was before, particularly as it will then possess no means whereby it can (in the broadest sense) protect itself against failure.

– Wynne Godley, Commonsense Route To A Common Europe, in The Observer, 6 January 1991.

Greece had large negative current account balance of payments and Germany had the opposite over the lifetime of the Euro.

Yet, there are some economists who argue that the Euro Area crisis is not a balance of payment crisis. Of course there are other aspects to the crisis as well but this in my view is the main issue. There was a debate between Sergio Cesaratto and Marc Lavoie on this. Now there is a new paper in the most recent issue of ROKE (Review of Keynesian Economics) by Eladio Febrero, Jorge Uxó and Fernando Bermejo which discusses this. The Wayback Machine/Internet Archive link is here if you are reading it after the journal puts the paywall again.

The authors seem to be against Sergio Cesaratto view. Since I agree with Cesaratto, I thought I should comment on it.

The fundamental problem of the Euro Area is that it doesn’t have a central government. If there had been a central government like the US federal government, with large fiscal powers, the Euro Area crisis would have been far less deeper. This is because weaker regions would have been recipients of “fiscal transfers”, i.e., receive more government expenditure than what they send in taxes.

Fiscal transfers can be seen transactions in the balance of payments of Euro Area countries if the EA had a central government. The way to do balance of payments for monetary and political unions is explained in the IMF Balance of Payments and International Investment Position manual. Take a country like Greece. The Euro Area government would be considered external to Greece. Same for other countries. But for the Euro Area as a whole, the central government would be considered inside the Euro Area.

So government expenditure would appear in Greek exports in the goods and services account and transfers in the secondary income account. Taxes would appear only in the latter.

So there is an improvement in the current account balance of payments for regions compared to the case when there is no central government. Current account balances accumulate to the net international investment of the whole country. A country which has persistent imbalances would have negative net international investment position, i.e., indebtedness to other countries.

So fiscal transfers keep all this in check by improving the current account balance. So if the Euro Area had a central government, debts of a country like Greece would be in check.

By joining the half-baked half-way house, Greece got an overvalued exchange rate and easier access for other Euro Area countries into its markets and its external imbalances worsened in its lifetime inside the monetary union.

Nations with high current account deficits will also have higher public debt than otherwise and would need international investors to buy the debt which residents won’t. Normally the price would adjust to bring international investors but as we have seen, sometimes there is no price and a fall in bond prices might lead to expectations of further fall leading external investors to dump the bonds instead of finding them attractive.

The trouble with Febrero et al. is that they seem to think that the European central bank can purchase all government debt of nation. Certainly, the European Central Bank (ECB) has stepped in at various times to ease the pressure on government bond markets. But the trouble with this is that there are under some conditions such as assuming it can impose tight fiscal policy on the governments it is helping.

If the Euro Area treaty is modified to allow countries to have independent fiscal policies, then for stability, the ECB has to buy bonds without limits and can keep accumulating. It is a political mess. A country like Germany could argue that it is writing an open cheque to Greece.

A political union wouldn’t have such problems. National level governments such as the Greek government would have fiscal rules on them, and hopefully not the supranational government. This is like the United States where state governments have rules on their budgets.

In contrast, if the ECB guarantees Greece’s debt, it has to impose some rules and since Greece is not recipient of any equalisation payments—the fiscal transfers—its performance is still dependent on its competitiveness. This is because competitiveness would affect the Greece government’s fiscal balance and hence put a deflationary pressure on Greece’s fiscal stance.

On the other hand, a Euro Area with a central government would imply Greece is recipient of substantial equalisation payments and its competitiveness isn’t so binding.

An argument of the economists arguing that the European monetary system has this thing called TARGET2 and that the intra-Eurosystem balances (i.e., automatic credits offered by one national central bank to another) can rise without limit is used in this paper. This is highly misleading. It is true but one should look at the changes in debits and credits elsewhere. Suppose a country like Greece sees a large private financial outflow. While T2 can absorb a lot of this—much more than anyone imagined—in the late stages, Greece banks become heavily indebted to their national central bank, The Bank of Greece. When they run out of collateral, the rules under ELA, Emergency Liquidity Assistance, is triggered. So TARGET2 or more accurately the Eurosystem cannot absorb everything.

In summary, the Euro Area cannot do without a central government in the long run. Anyone who thinks that the ECB or the Eurosystem can buy whatever residual debt private investors doesn’t understand that in such a system, Euro Area governments are given an open cheque.

The difference between not having a central government and a central government is that in the former, there is no equivalent income flow as in the latter. The Eurosystem purchases would affect the financial account of balance of payments, not the current account.

One of the noticeable assertions of the paper is:

With T2, there is just one currency. This means that if foreign exchange markets did not exist, there could not be a BoP crisis, so that the cause of the crisis should be found elsewhere.

The trouble with this is that it sees it only as a currency crisis. But the fact is that countries whose external position were weak were the ones running into trouble in the Euro Area. Had current account deficits not blown up, countries would have had better fiscal balance since the current account balance and the budget balance are related by an identity and even behaviourally as can be seen in stock-flow consistent models. In crisis times, foreign investors are more likely to shift their funds in their home countries. With better balance of payments, public debt would be held more internally and there would have been less pressure on government bonds.

There are comments in the paper about too much credit etc. This is true, but then the Euro Area crisis would have looked more like the economic and financial crisis affected the United States.

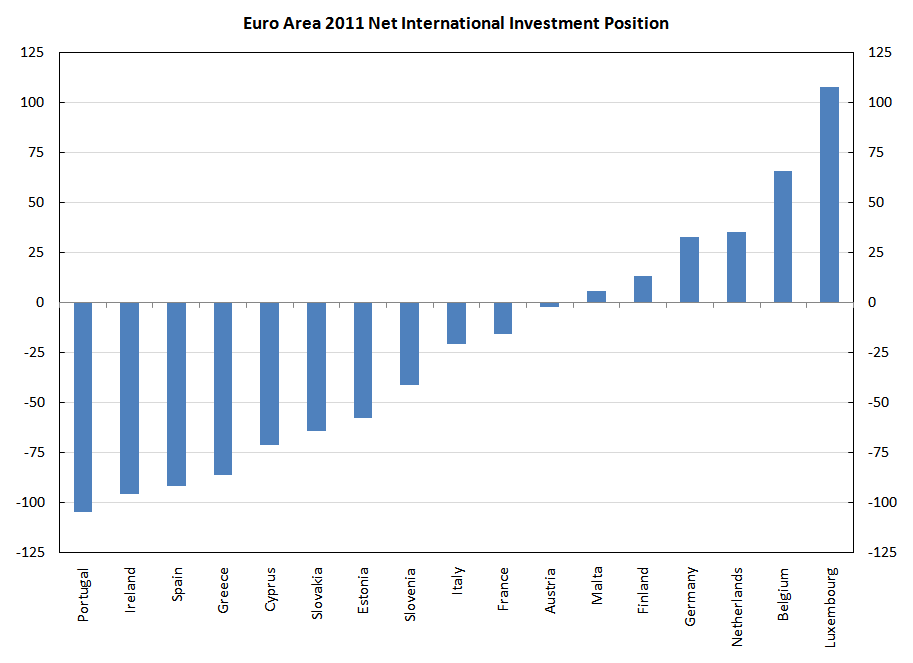

Here’s the the NIIP of Euro Area countries in 2011.

Doesn’t this explain why Germany was in a better position than Greece when the crisis started heating up? Or that Netherlands was in a better position than Portugal?

Ha-Joon Chang On Why Manufacturing Is Still The Engine Of Growth

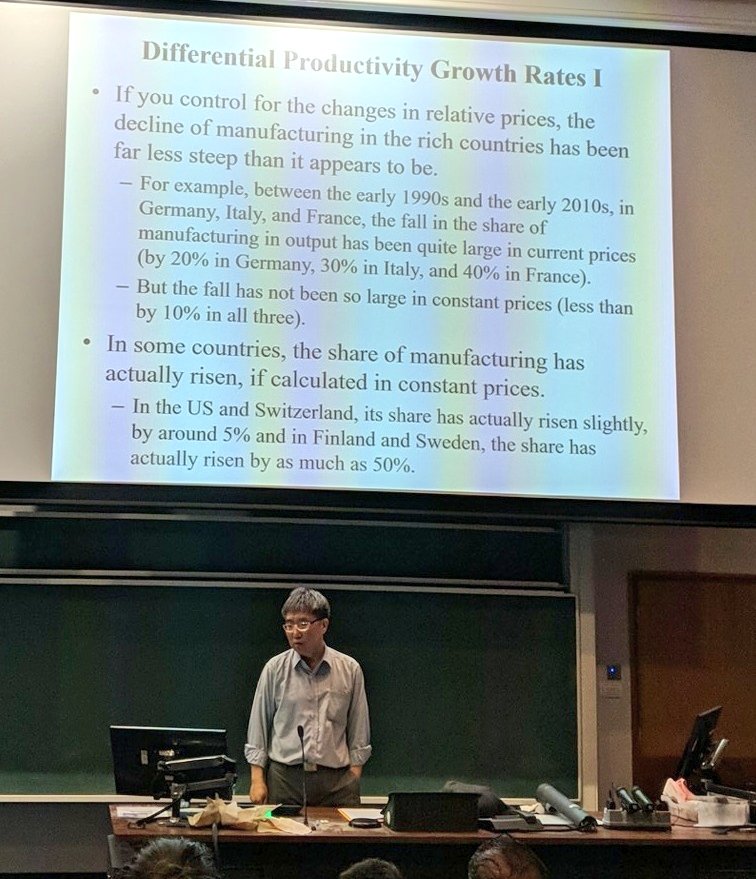

Recently the University Of York hosted a talk by Ha-Joon Chang on deindustrialisation. The title of the talk was: Manufacturing Matters – The Myth Of Post-Industrial Knowledge Economy.

picture credit: Ingrid Kvangraven

You will find a lot of emphasis on manufacturing in Nicholas Kaldor and Wynne Godley’s work. Why is manufacturing important? Wynne Godley emphasised the supremacy of manufactured products over services in exports, since it’s more difficult to export services. Nicholas Kaldor also suggested increasing returns to scale in manufacturing.

We are frequently told that manufacturing lost its importance. Ha-Joon Chang’s talk is precisely in debunking this myth. As Wynne Godley emphasised, while the share of manufacturing in GDP has fallen, the share of imports has risen a lot. Ha-Joon Chang also points out another important point that superficial reading of data might mislead. So because of offshoring and how the data is recorded by national accounts, it might look like there is no manufacturing happening. For example—and the real thing is more complicated—Apple manufactures phones, computers, etc., in China and it is recorded as an export of services in U.S. balance of payments and hence not as manufacturing in the production account of U.S. national accounts.

You can view the talk on YouTube. It has slides and audio.

A Comment On Wynne Godley And Non-selective Protectionism On The Article XII Of The GATT

Nick Edmonds commented on my post Wynne Godley And Non-Selective Protectionism—which documented all the references where Wynne Godley proposes the usage of the Article XII of the GATT—pointing out that the Article XII of the GATT can only be invoked reserve assets are under threat.

Hence it is difficult for the United States to invoke it. I agree with this. It’s looks more designed for nations who accumulate reserve assets and for whom sales of reserve assets is an important way to finance current account deficits. The U.S. has some reserve assets but is under no imminent threat. (And it finances its current account deficit mainly by net incurrence of liabilities instead of sale of reserve assets).

The WTO page Technical Information on Balance of Payments has this information:

Introduction

Under the rules of the WTO, any trade restriction taken by a Member must be consistent, or in compliance, with the rules of the international trading system. Under the provisions of Article XII, XVIII:B and the “Understanding of the Balance-of-Payments Provisions of the GATT 1994”, a Member may apply import restrictions for balance-of-payments reasons.

GATT: Articles XII and XVIII:B

Article XII and XVIII:B in their current form were redrafted in 1957 by the Working Party on Quantitative Restrictions. At that time, balance-of-payments measures referred to quantitative restrictions and were an exception to Article XI which prohibits the use of quantitative restrictions. Article XII can be invoked by all Members and Article XVIII:B by the developing country Members (defined as those in the early stages of development and with a low standard of living.

The basic condition for invoking Article XII is to “safeguard the [Member’s] external financial position and its balance-of-payments”; Article XVIII:B mentions the need to “safeguard the [Member’s] external financial position and ensure a level of reserves adequate for the implementation of its programme of economic development”. Both Articles refer to the need to “restore equilibrium on a sound and lasting basis”. While Article XII mentions the objective of “avoiding the uneconomic employment of resources”, Article XVIII:B refers to “assuring an economic employment of production resources”.

Article XVIII:B contains somewhat less stringent criteria than Article XII. Article XII (para. 2)states that import restrictions “shall not exceed those necessary (i) to forestall the imminent threat of, or to stop, a serious decline in its monetary reserves” or (ii) “…in the case of a contracting party with very low monetary reserves, to achieve a reasonable rate of increase in its reserves”.

Article XVIII:B (para. 9) omits the word “imminent” from the first condition and refers to an “inadequate” level rather than a “very low” level of reserves; “adequate” is defined as “adequate for the implementation of its programme of economic development”.

Both Articles require Members to progressively relax the restrictions as conditions improve and eliminate them when conditions no longer justify such maintenance.

The 1979 Declaration

After the Tokyo Round, the 1979 Declaration on Trade Measures Taken for Balance-of-Payments Purposes (BISD 26S/205) extended the disciplines to all trade measures imposed for balance-of-payments reasons, not just quantitative restrictions. Thus all trade measures taken for balance-of-payments purposes come within the purview of notification and consultation requirements.

The 1979 Declaration introduced three new conditions for the application of balance-of-payments measures: (i) that preference shall be given to the measure which has “the least disruptive effect on trade” while abiding by disciplines provided for in the GATT; (ii) that the simultaneous application of more than one trade measure for balance-of-payments purposes shall be avoided; and (iii) that “whenever practicable, contracting parties shall publicly announce a time schedule for the removal of the measures”. It also spelled out that measures should not be taken “for the purpose of protecting a particular industry or sector”.

…

I am sure Wynne was aware of this, so it’s curious why he mentions it over the years. If anyone knows, I’ll be grateful!