I am reading Dani Rodrik’s The Globalization Paradox and borrowed the title for this post.

I am curious as to what Barry Eichengreen has to say in his talk at the Federal Reserve’s annual forum at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. He is the author of the book Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise And Fall Of The Dollar And The Future Of The International Monetary System – one of the books I want to read soon. The phrase Exhorbitant Privilege was coined in the 1960s by the then French Finance Minster Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. The term refers to the high ability of the United States (and directly and indirectly, the United States government) to borrow in US$ to finance its balance of payments deficit.

To some extent, the scale and timing of the Federal Reserve’s emergency operations during the credit crisis which started around 2007 has helped maintaining the hegemony of the US$ for a while and Barry Eichengreen knows that. This United States Government Accountability Office (GAO) report Federal Reserve System – Opportunities Exist To Strengthen Policies And Processes For Managing Emergency Assistance is a nice reference for the kind of operations done by the Fed, especially international swap lines. Many central banks made use of the swap lines and lent large quantities of US$ to the banking system because banks were facing funding issues in dollars.

Back to the Jackson Hole Symposium. Everyone is waiting for the ECB Chairman Jean-Claude Trichet’s talk. Meanwhile Christine Lagarde, IMF’s chief touched on some issues about imbalances in her speech. She rightly points out that

… risks have been aggravated further by a deterioration in confidence and a growing sense that policymakers do not have the conviction, or simply are not willing, to take the decisions that are needed.

which is quite right, IMO because this crisis needs coordination at a scale never seen before. She also points out that

As we all know, a major cause of the crisis was too much debt and leverage in key advanced economies. Financial institutions engaged in practices that magnified, disguised and fragmented risk, while households borrowed too much. Experience tells us that these excesses (combining both housing and financial crises) take a long time to work off—and require decisive action. We have made some progress, but not enough to unshackle growth.

I am by no means downplaying what has been done. In 2008, governments took bold action to prevent a calamitous collapse in demand. They offset private contraction with fiscal expansion and used public resources to recapitalize financial institutions. They strengthened financial regulation, and reinforced the capacity and resources of international institutions. And monetary authorities did their part as well.

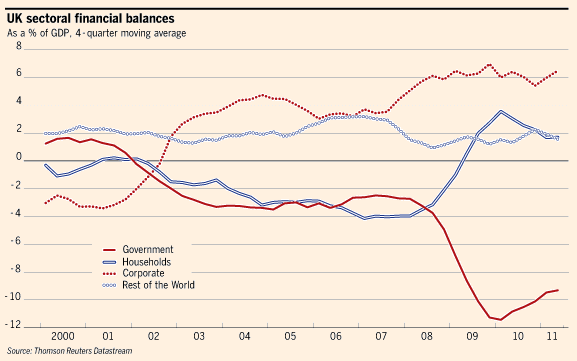

But today, it is public sector balance sheets themselves that are in the firing line. Today, the headline problems are sovereigns in most advanced economies, banks in Europe, and households in the United States. Adding to this—global growth is also being held back by policies that slow demand in some key emerging market economies while balance sheet risks are increasing in others.

The fundamental problem is that in these advanced economies, weak growth and weak balance sheets—of governments, financial institutions, and households—are feeding negatively on each other. If growth continues to lose momentum, balance sheet problems will worsen, fiscal sustainability will be threatened, and policy instruments will lose their ability to sustain the recovery.

which is quite right. Fiscal expansion has helped nations recover from the private sector imbalance but fiscal policy alone cannot achieve everything. However, somewhere her message won’t work well because she mentions earlier in her speech that

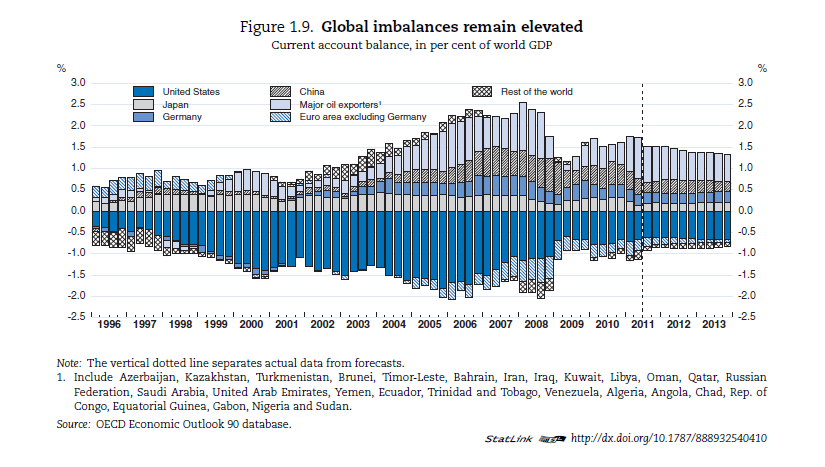

Two years ago, it became clear that resolving the crisis would require two key rebalancing acts—a domestic demand switch from the public to the private sector, and a global demand switch from external deficit to external surplus counties. On the first, the idea was that strengthened private sector finances would allow the engine of growth to switch back from the public to the private sector. On the second, the idea was that higher demand in surplus countries would make up for a lower spending path in deficit countries. But the actual progress on rebalancing has been timid at best, while the downside risks to the global economy are increasing.

implying thereby that coordinated fiscal policy (expansion) has no role in the long run, at least giving the impression to the reader/listener. However, she is right in stressing that surplus nations need to take up the task of rebalancing.

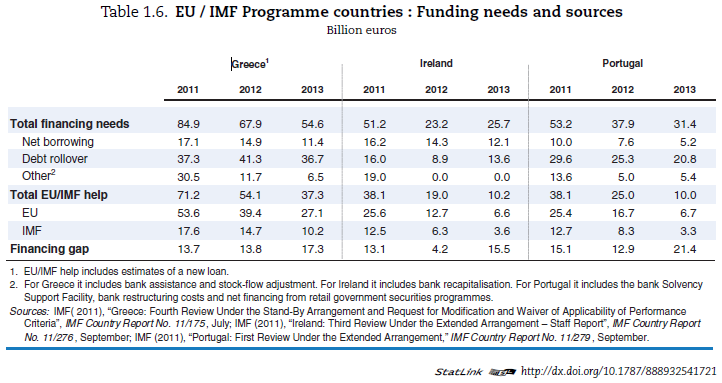

While talking of “urgent recapitalization” banks in Europe require, Lagarde also talks of a common vision for Europe:

Third, Europe needs a common vision for its future. The current economic turmoil has exposed some serious flaws in the architecture of the eurozone, flaws that threaten the sustainability of the entire project. In such an atmosphere, there is no room for ambivalence about its future direction. An unclear or confused message will add to market uncertainty and magnify the eurozone’s economic tensions. So Europe must recommit credibly to a common vision, and it needs to be built on solid foundations—including, for example, fiscal rules that actually work.

but no mention of a fiscal union! Most people – economists at least – would take the above to mean a plan to work toward achieving targets for deficits and public debt – an impossible dream.

Lagarde’s conclusions are right

There is a clear implication: we must act now, act boldly, and act together.

but this comes only by at least and not limited to coordinating fiscal policies not by “fiscal consolidation” – a phrase which literally suggests a fiscal contraction.

Conclusion

The IMF is a part of the problem but Christine Lagarde’s heart is in the right place – she needs to carefully think about how fiscal policy really matters and convey to others some of the ideas she has thought of, since they are slightly different from the IMF’s traditional beliefs. How far she goes will be interesting to see.

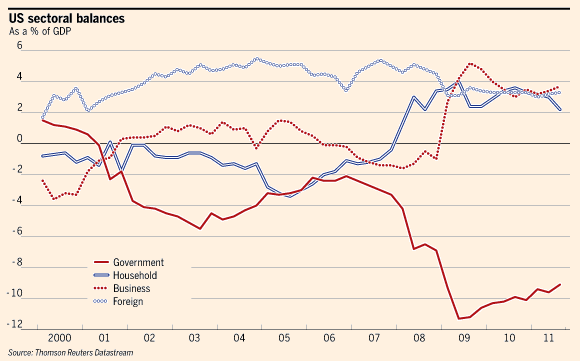

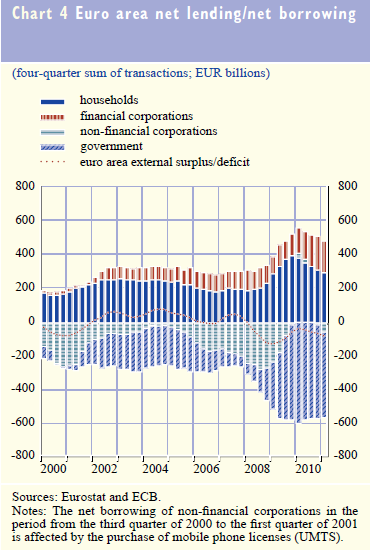

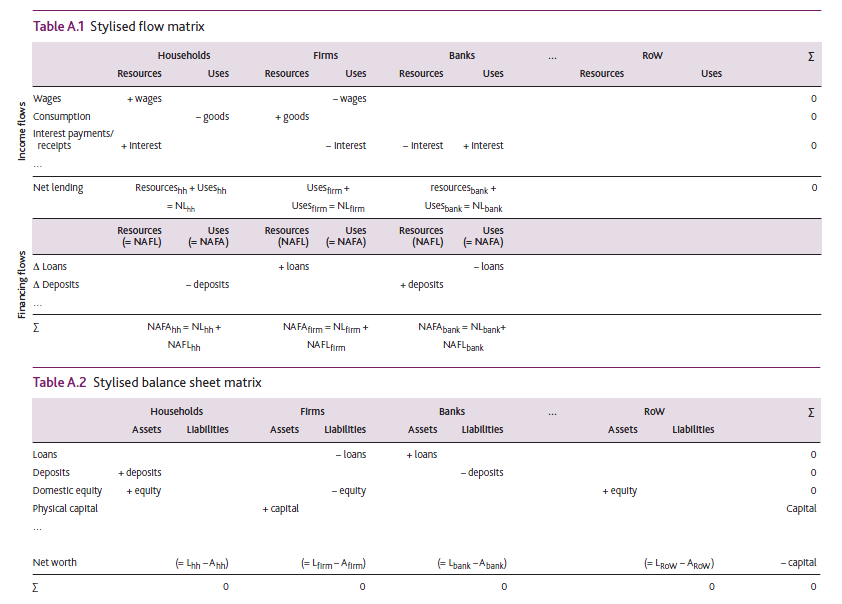

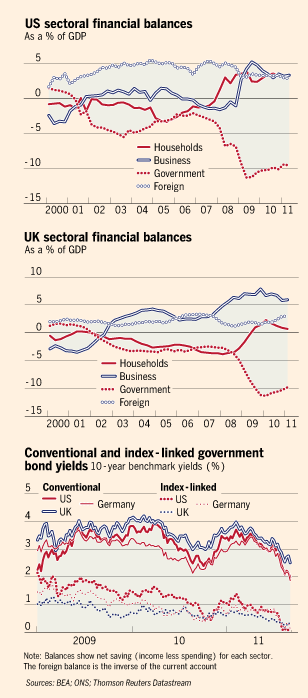

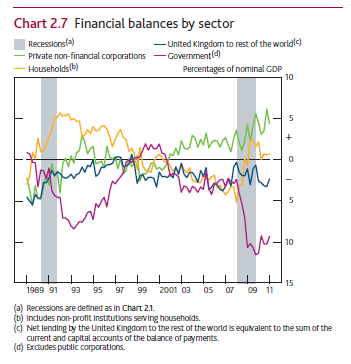

The sectoral balances identity

NAFA = PSBR + BP

(where NAFA is the private sector net accumulation of financial assets, PSBR is the public sector borrowing requirement to finance its deficit and BP is the current balance of payments) and the approach which is built around this, implies that if the public sector wants more saving, the government has no choice but to accommodate this demand unless it is prepared to run the economy at less than full employment. However, it doesn’t mean that the government has the ability to fully relax its fiscal stance up to constraints from the supply side, because if domestic demand starts expanding faster than domestic output, the nation’s balance of payments situation will suffer and this can be resolved only by correctly negotiated international policies which is good for all. The IMF should look at it that way instead of recommending fiscal expansion as a temporary measure.

Update

For a different take on Lagarde’s speech check Zero Hedge

Update 2:

Financial Times has a post Lagarde calls for urgent action on banks on this. The writer points out that

On fiscal policy, she continued the IMF’s change of emphasis away from immediate fiscal tightening, and towards fiscal programmes that reduce deficits over the long-term but which allow spending to continue while economies stay weak.