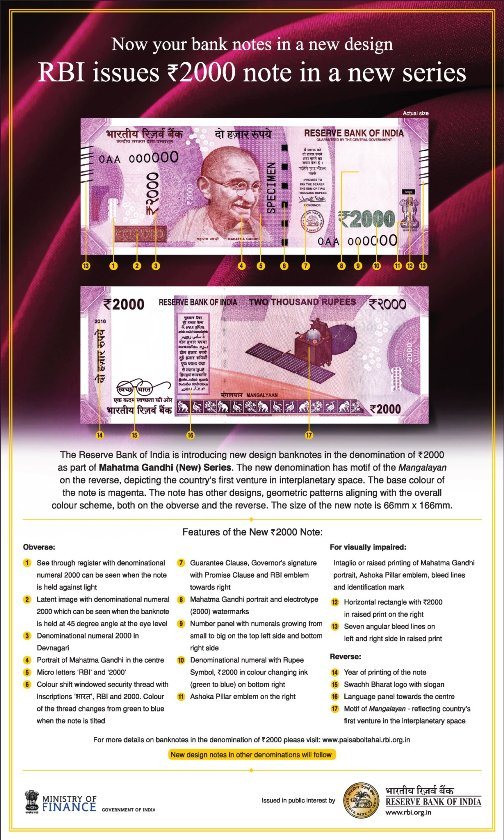

On 8th November 2016, at around 8pm, the Prime Minister of India, in a shock announcement, declared that 86% of currency notes in circulation—notes denominated ₹500 and ₹1,000—are no longer legal tender from midnight. Instead new notes with denominations ₹500 and ₹2,000 will be issued. The press is calling this “demonetisation”, although “remonetisation” seems to be a better word.

Picture source: RBI on Twitter. Click picture for higher resolution

These notes are worth about $7.37 and $14.75 (at today’s exchange rate USDINR = 67.811). Although this is not much for people resident in the advanced world, it is quite a lot for Indians, especially the poor.

Holders of these currency notes are given time till 30th December to either

- exchange these currency notes with banks who will provide the holders with old currency notes denominated ₹100, ₹50, ₹50 or ₹10, or

- deposit them in their bank accounts.

The reasons provided were that there is a lot of counterfeiting happening from across the border and there is a lot of “black money” with Indians. Now there is a lot of political rhetoric around “black money” but Indians have this imagery that everyone doing immoral or illegal things with their finances has hidden a lot of currency notes in the water tanks of their homes. Before the Prime Minister’s Bhartiya Janata Party, won the elections, he promised to bring in “black money” worth $40 trillion (no typo!) from abroad and promised that every poor Indian will easily get around $30,000. But having failed in this, he feels pressured to do something about it.

Now, as Pronab Sen points out in Mint, that is hardly the case. The one doing shady things with their financial statements may hold wealth in various forms such as real estate, gold, foreign exchange, foreign accounts, via Panama etc. Moreover, people have been standing in queues in banks and ATMs for the whole day, just to exchange their notes. This is because the Indian government and the central bank didn’t make the new notes immediately available. Since there is a liquidity shortage, and that since a lot of people live in daily wages, there have been delays in payments of wages. People have postponed their expenditures to subsistence levels because it’s not clear how long the shortage will last.

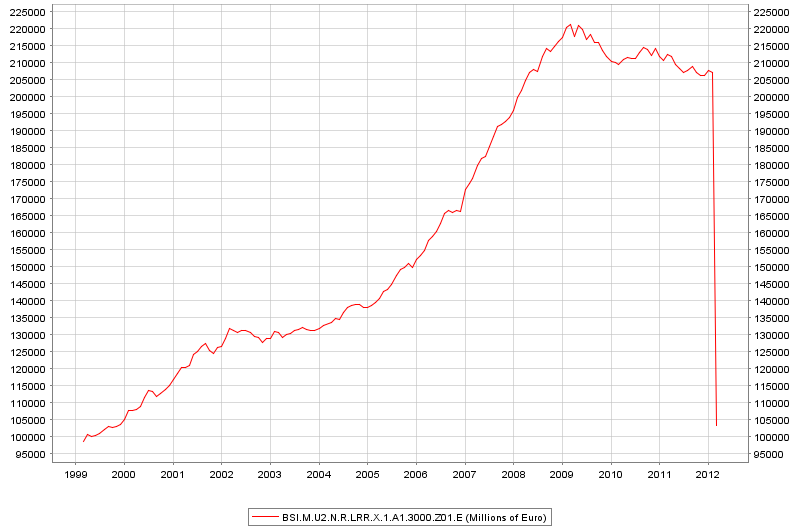

How does the Indian government hope to gain from this operation? Currently, currency notes equivalent of around $222 bn of old notes are no longer legal tender. India’s annual GDP was $1.51 tn in 2015 for comparison with the US (where the currency in circulation is $1.48 tn and annual GDP was $18.44 tn, annualized in Q2 2016 and India’s population is 1.25 bn while US population is 319 mn). When notes are returned and new currency is issued, the Reserve Bank’s liabilities changes because some people won’t return their currency notes in the fear that their finances will be investigated. How much it is is anybody’s guess. But let’s say currency notes equivalent of $210 bn is returned. The RBI will see this as income from this operation and will pay an additional dividend of $12 bn to the government. The government can raise its expenditure because of higher tax revenues.

But since all this was poorly implemented and 11 people have died so for this political propaganda of the government. It’s not like in the Western world here in India. There is a parallel “informal economy” in India and a large population is extremely poor. It is difficult to calculate the loss of output.

I want to distract here to Monetarism and the relevance of this to monetary theory especially the causality from money to prices and output. It’s usually argued by Post-Keynesians that the causality is from price and output to money but as central bank asset purchases (“QE”) have highlighted, there is causality in the reverse direction also via rise in prices of financial assets causing a wealth effect.

Right now in India, there’s a drop of liquidity and from the story above, I hoped to convince you that there is a causality from money to output. People’s wealth hasn’t dropped but liquidity has. So Monetarism can have some truth to it, in selected cases. In standard Post-Keynesian theory, it is assumed that all demand for “money” is accomodated. But right now, this isn’t the case, leading to the reverse-reverse causality.

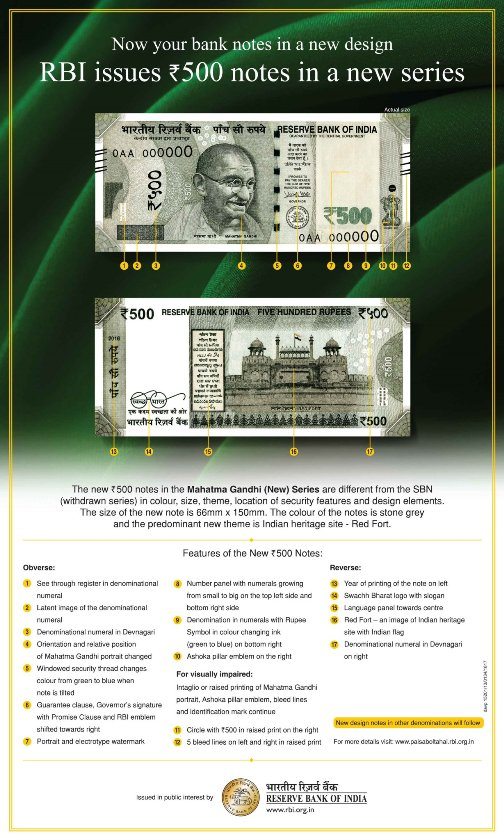

Picture source: RBI on Twitter. Click picture for higher resolution