Recently, a U.S. politician Rick Perry cited Say’s Law:

Here’s a little economics lesson: supply and demand. You put the supply out there and the demand will follow.

Just saying that implicitly rejects the Keynesian principle of effective demand.

But it’s interesting to see that according to Nicholas Kaldor, the principle of effective demand is not a rejection of Say’s Law.

What is Say’s Law. Usually this paragraph—from Jean Baptiste Say’s book, A Treatise On Political Economy; Or The Production, Distribution, And Consumption Of Wealth, published in 1821, page 38—is referred:

It is worth while to remark, that a product is no sooner created, than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value. When the producer has put the finishing hand to his product, he is most anxious to sell it immediately, lest its value should diminish in his hands. Nor is he less anxious to dispose of the money he may get for it; for the value of money is also perishable. But the only way of getting rid of money is in the purchase of some product or other. Thus, the mere circumstance of the creation of one product immediately opens a vent foi

other products.

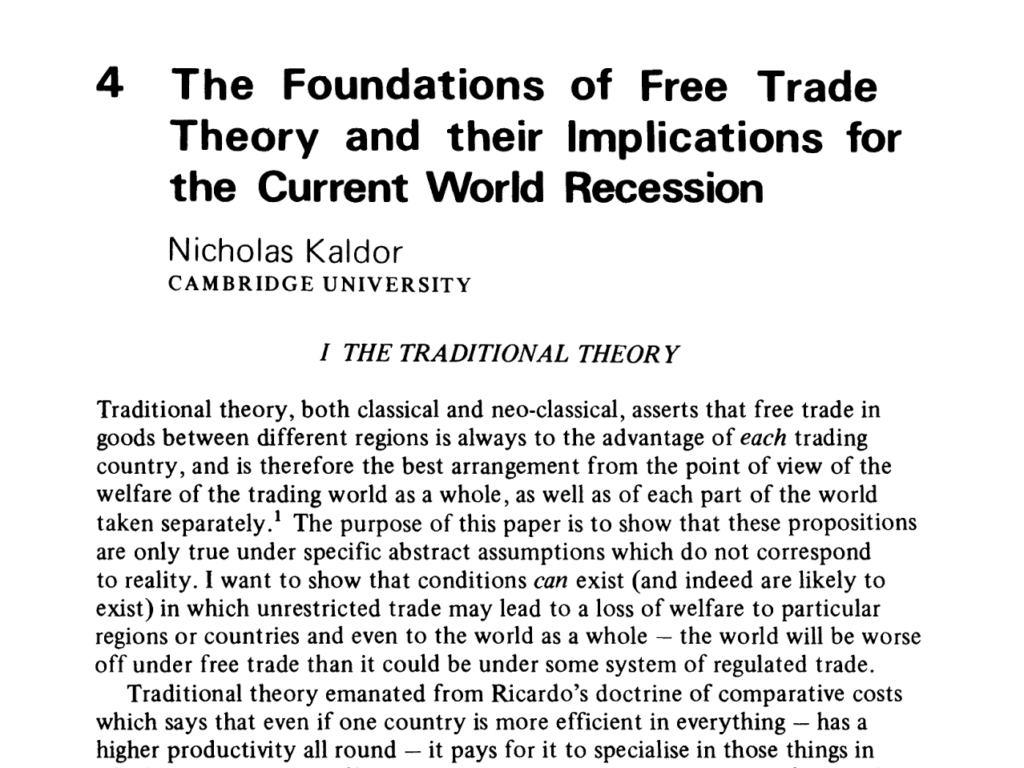

In Keynesian Economics After Fifty Years, in the book, Keynes And The Modern World, ed. George David Norman Worswick and James Anthony Trevithick, Cambridge University Press, 1983, page 5, Kaldor says:

The Principle Of Effective Demand

The core of Keynes’s theory is the principle of effective demand which is best analysed as a development or refinement of Say’s law, rather than a complete rejection of the ideas behind that law.

Further, on page 6:

The originality in Keynes’s conception of effective demand lies in the division of demand into two components, an endogenous component and an exogenous component. It is the endogenous component which reflects (i.e., is automatically generated by) production, for much the same reasons as those given by Ricardo, Mill or Say — the difference is only that in a money economy (i.e. in an economy where things are not directly exchanged, but only through the intermediation of money) aggregate demand can be a function of aggregate supply (both measured in money terms) without being equal to it — the one can be some fraction of the other. To make the two equal requires the addition of the exogenous component (which could be one of a number of things, of which capital expenditure – ‘investment’ – is only one) the value of which is extraneously determined. Given the relationship between aggregate output and the endogenous demand generated by it (where the latter can be assumed to be a monotonic function of the former), there is only one level of output at which output (or employment) is in ‘equilibrium’ – that particular level at which the amount of exogenous demand is just equal to the difference between the value of output and the value of the endogenous demand generated by it. If the relationship between output and endogenous demand (which Keynes called ‘the propensity to consume’) is taken as given, it is the value of exogenous demand which determines what total production and employment will be. A rise in exogenous demand, for whatever reasons, will cause an increase in production which will be some multiple of the former, since the increase in production thus caused will cause a consequential increase in endogenous demand, by a ‘multiplier’ process.

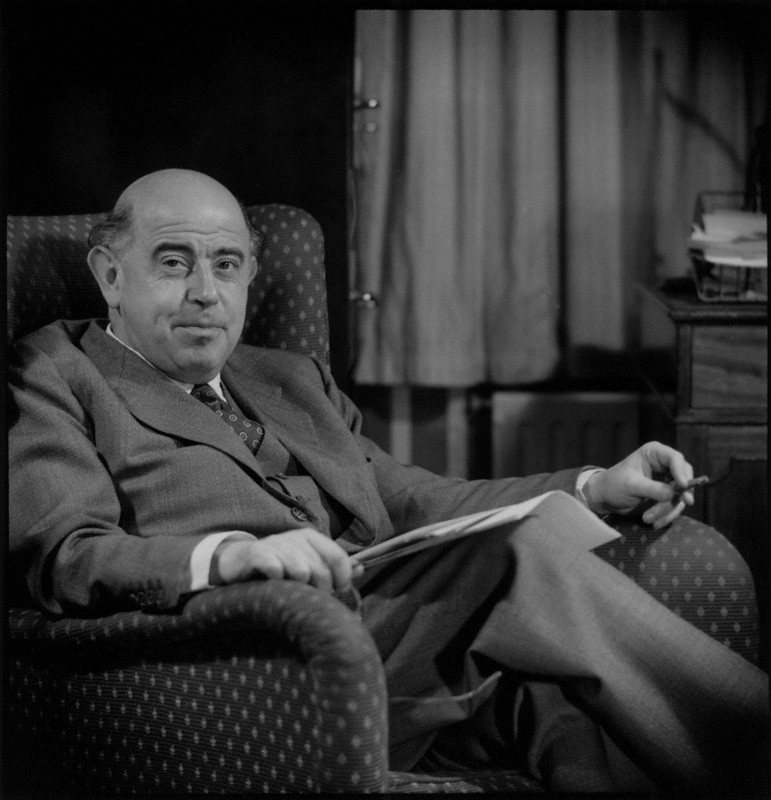

Nicholas Kaldor, 1957. Photo via: NPR

and further on page 9:

A capitalist economy (for reasons explained below) is not ‘self-adjusting’ in the sense that an increase in potential output will automatically induce a correspond¬ing growth of actual output. This will only be the case if exogenous demand expands at the same time to the required degree: and as this cannot be taken for granted, the maintenance of full employment in a growing economy requires a deliberate policy of demand management … the mere existence of competition between sellers (‘firms’) will not in itself ensure the full utilization of resources unless all firms expand in concert. Any one firm, acting in isolation, may find that the market for its own products is limited, and will therefore refrain from expanding its production even when its marginal costs are well below the ruling price. Under these conditions involuntary unemployment could only be avoided if something – the growth of some extraneous component of demand – drives the economy forward.

So Say’s law is not wrong, it’s incomplete. Nonetheless, it’s not surprising that politicians like Rick Perry are going to use it, mislead and reject the Keynesian principle of effective demand.

tl;dr

Say’s law: supply creates demand.

Principle of effective demand: demand also creates its own supply. supply creating demand doesn’t mean the economy is running at full capacity.