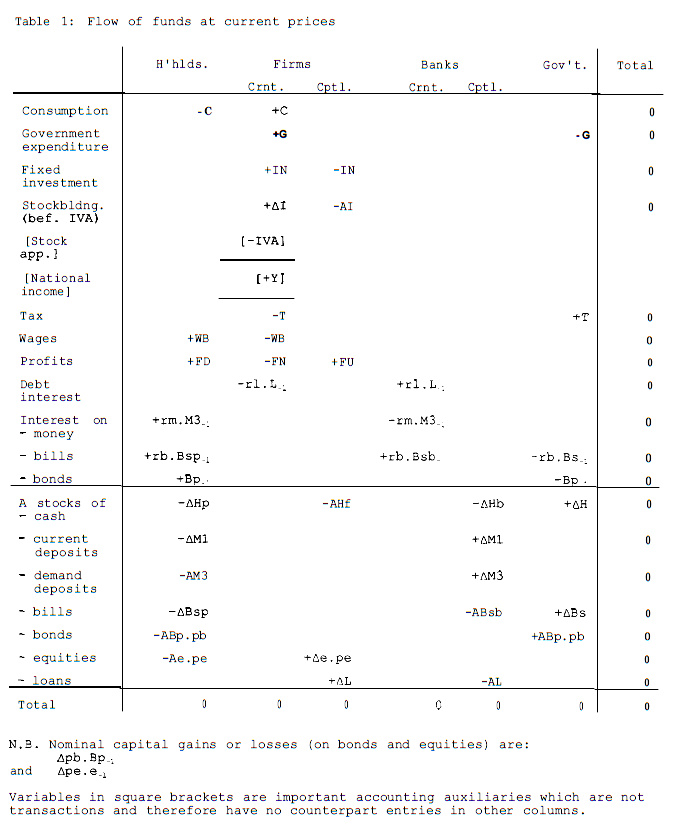

Let us take the public sector budget equation:

G – T = ΔH + ΔB

Inspired by Milton Friedman’s popularity in the 1970s and the 80s, most textbooks and journal articles incorrectly claim that the central bank “controls” the money stock (such as M0, M1, M2 etc). Simultaneously they also claim – rightly – that the central bank targets the short term interest rates.

Recently, Alan Blinder – formerly Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve Board – said this in New York Times’ Room For Debate (h/t wh10):

Remember “conventional” monetary policy? The Federal Reserve shortens recessions by creating more bank reserves (“printing money”), which fuels a multiple expansion of the money supply and credit because banks don’t want to hold excess reserves. So they get rid of them making more loans and deposits, which also lowers short-term interest rates. Compare that to current reality: Banks are content to hold over $1.6 trillion in excess reserves, short-term interest rates are stuck near zero, and Fed policy often works on long-term interest rates instead. No, this is not your father’s monetary policy, and the old ways of teaching about it simply won’t do.

Einstein declared that everything should be made as simple as possible, but not more so. The crisis has made the “but not more so” part more important.

Alan Blinder is a good economist, but I guess the best way to put it is that the usual story is pure fantasy.

(To be a bit technical, let us assume – in what follows – till the next section that the central bank is targeting overnight interest rates using a corridor system)

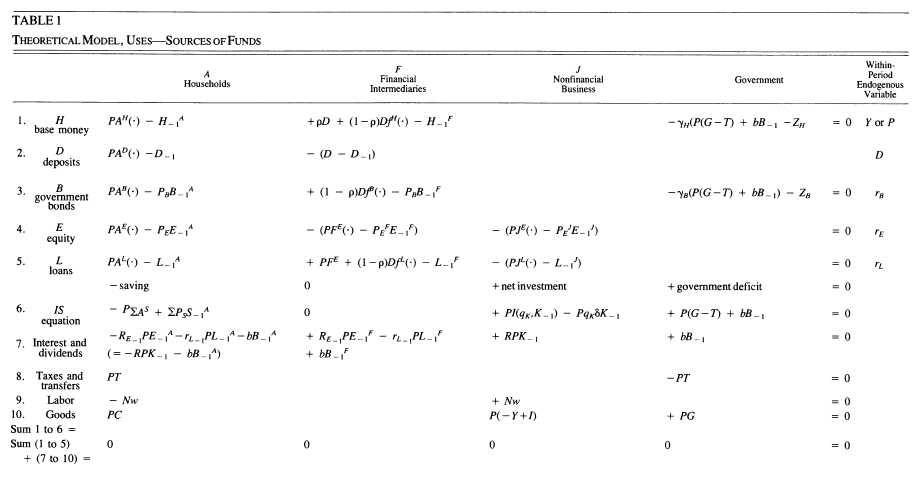

Apart from the chimerical money multiplier story, neoclassical economists also bring in the government’s budget into the story. So the story goes that if the government wants to increase its expenditures, it will sooner or later ask the central bank to “monetize” its deficit. So the government’s Treasury and the central bank can decide the proportion of the deficit which is financed by issuing H (high-powered-money or currency notes and reserves/bank settlement balances) and B (government bills and bonds). This – higher issuance of H will cause a sequence of events involving higher private expenditure inevitably resulting in price rise and higher inflation in this story.

In my post Open Mouth Operations, I discussed two kinds of open market operations – temporary and permanent. As we saw, when the private sector needs more currency notes, the central bank must neutralize this outflow by engaging in permanent open market operations. The central bank just targets/sets the short term interest rates and simply cannot be anything but defensive.

Neoclassical economists however, think of this as purely being decided by the central bank (or the central bank acting under pressure by the government) and the process is called debt monetization. Since this involves purchases of government bonds, debt monetization is a process of purchases of government bonds by the central bank (directly from the government or in open markets) in order to increase the stock of money.

We however saw that this decision of the central bank is based purely on the private sector’s needs for currency or banks’ need for higher reserves/settlement balances and the central bank must act defensively.

This was understood well by members of the “New Cambridge” School and some of their critics. In an article attempting to show the full working of their model, New Cambridge Macroeconomics And Global Monetarism – Some Issues In The Conduct Of U.K. Economic Policy, 1978, Martin Fetherston and Wynne Godley say:

… It will further be assumed that domestic monetary policy involves supplying cash and bonds in whatever amounts necessary to maintain private (and overseas) portfolio equilibrium at given (i.e., baseline) rates of interest…

This was from a conference Public Policy In Open Economies and Alan Blinder understood this – in a reply to the New Cambridge model, Whats New And Whats Keynesian In The New Cambridge Keynesianism (same link as above) he said:

Fiscal policy can, therefore, have no immediate effect on these asset demands. (It has a longer-run effect through raising net wealth.) The central bank monetizes just enough government debt to keep interest rates from rising, so there can be no “crowding out.”

on the New Cambridge model. i.e., as we move forward in time, because the private sector has higher wealth, the Bank of England will purchase government debt depending on how much of this wealth the private sector wants in the form of money.

Hence we can say that monetization is endogenous. So if the central bank purchases more government bonds than it is supposed to, banks will have more settlement balances and the central bank’s target will fall to the lower end of the corridor and will be forced to sell bonds in equal quantities. The description of the corridor and floor systems can be found in the post Open Mouth Operations.

The Floor System And Central Bank Large Scale Asset Purchases

In recent times (since the last three years), central banks especially the Federal Reserve – who have adopted a floor system – have been purchasing a lot of domestic government bonds in the open markets (and also other securities such as “agency debt” and “agency MBS”). This is also called “QE”, and it’s a bad phrase. However does this mean the private sector has “excess money”? The private sector’s wealth allocation decision depends on its portfolio preferences between various forms of wealth and since purchases also lead to a reduction of long term government bond yields (as compared to the case when the asset purchase program hadn’t been carried out) and hence the private sector wishes to hold less of its wealth in the form of government bonds and more in the form of money – hence sold the bonds the Federal Reserve intends to buy!

Of course the result is that banks have more central bank reserves than they wish to hold, but as a whole the banking system won’t convert these settlement balances into currency notes unless the non-bank private sector wishes to hold them. If the non-bank private sector needs more currency notes, banks will easily accommodate this need and so will the central bank and this need is not a function of how much settlement balances the banking system holds. And it won’t cause price rises either because “money” doesn’t lead to inflation. The strategy of the central banks in reducing long term bonds comes with asking the banks to hold the settlement balances for some time (and keeping them happy by paying interest on the reserves) and the Federal Reserve may sometime phase out the program by an “exit strategy”. However this has nothing to do with “inflation expecations” or some chimerical story about runaway inflation waiting to happen.

The Federal Reserve’s strategy has been to create more demand by reducing long term rates so that depending on the interest elasticity (as opposed to income elasticity) of investment by the private sector and/or its animal spirits, there may be higher activity. But since income elasticity effects are stronger, the LSAP hasn’t really worked as desired.

Private expenditure depends mainly on private income and LSAPs do not directly affect private expenditure. There can be indirect effects due to portfolio preferences – because LSAPs may induce the private sector to purchase other asset classes such as corporate equities leading to a rise in stock prices, leading to wealth effects via capital gains. Hence we see a lot of references to James Tobin’s work in central bank papers on this.

There were other effects which didn’t work as desired – such as refinancing of existing mortgages due to lower interest rates and this leading to extra demand because it was thought that households will be able to refinance in huge numbers and this will lead to higher consumption because they will spend the difference they gain due to lower monthly outflows to the banking system.

Of course, none of this has anything to do with the fantasy story that there is an excess of money appearing out of nowhere and which will be eliminated via higher expenditures resulting in a permanent price rise and fantasy stories such as that.

To summarize, stories around money leading to inflation, excess money due to central bank government debt purchases etc have all led to tragic debates around macroeconomic issues.

Here’s from Marc Lavoie’s Changes In Central Bank Procedures During The Subprime Crisis And Their Repercussions On Monetary Theory (working paper here):

The financial crisis has made these features of the real world even more obvious and it should make clear that nearly all of mainstream monetary theory as applied to central banking is nearly worthless, as is for instance the infamous money multiplier fable and the presumed causal relationship running from bank reserves at the central bank to price inflation.

Also, while central bankers simply did not know that a crisis was going to hit but did good work (in my opinion) in preventing an implosion of the financial system, there is simply no need to congratulate them for having purchased government debt such as as done by Paul McCulley here and as done by Adair Turner here at the recent INET conference. Their arguments sound something like: central banks prevented a deflation of prices by purchasing government debt!

SMP

A qualification needs to be made in the above analysis on the purchases of Euro Area governments’ debt by the Eurosystem under the ECB’s Securities Markets Progam (SMP). Here some government debt markets have/had the potential to become “dysfunctional” (ECB’s phrase) and NCBs purchase(d) government bonds in the secondary markets to prevent government bond yields from rising forever as a result of a self-fulfilling prophecy of financial markets and its inability to absorb government debt because of suspicions that some governments could become insolvent in the long run. This is useful because it just postpones the day of reckoning or buys some time to reach an economic state of lower activity to keep some Euro Area nations’ net foreign indebtedness in check.

The ECB website and communications stress that these operations are being “sterilized” and hence keeps price stability in check but the explanation is right if there is a Monetarist causality from money to prices!