When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.

– attributed to Mark Twain, Reader’s Digest, September 1939.

Steve Keen has a blog post The Getting Of Wisdom in which he compares Tobin’s view in his 1963 paper Commerical Banks As Creators Of “Money” to his 1982 paper The Commercial Banking Firm: A Simple Model and finds Tobin has so many things (i.e., “loans create deposits” in 1963 to “loans create deposits” in 1982) in those years!

According to Keen:

The difference between the Old and New Tobin is as stark as that between the Old and New Testament. Not only is there an emphasis on the uniqueness of banks in that 1982 paper, Tobin also makes copious use of T-accounts and double-entry bookkeeping to explain why banks do matter. So just as the Testament message moved from “An eye for an eye” to “Turn the other cheek”, Tobin moved from “banks don’t matter and the belief that banks create money is a shibboleth”, to “banks are crucial to macroeconomics and they can and do create money”.

And whereas Tobin the Younger imagined that newly created bank money could be taken out of the system in a form other than bank deposits or cash, Tobin the Elder realizes that those are the only two options at the systemic level. Individuals might get out of bank deposits into (say) gold, but to do so they transfer money from their deposits in one bank into the deposits of the gold dealer in another bank. The only way for money not to be held in a bank is for it to be converted into some other kind of asset that is not a bank liability first. The only candidate here is cash—notes and coins—which you can insist on when you make a withdrawal (you might insist on gold instead, but a bank is under no obligation to deliver it in response to your withdrawal).

(italics in original, boldening mine)

Keen obviously is wrong when he says “the only way for money to be not held … ” because he first he misses the reflux mechanism where money can be extinguished by reducing indebtedness to the banking system. He obviously knows what “reflux” is but nonetheless misses it. Among other things he misses is that the bank can induce the non-banking public to shift in and out of money (or in the opposite case accommodate the non-banking public’s desire to change its portfolio) by changing bid/asks of markets they are dealers in such as government bond prices. So there is a price adjustment in the financial markets as well (leading to changes in deposits)

[Of course Keen attributes it to Tobin but looking at his agreeing tone, looks like it his own claim].

Others examples include but not limited to – a shift of deposits abroad with accommodative transactions which do not bring back the deposits to the original level, a “Treasury Supplementary Financing Operation” type of operation by the government Treasury which reduces the deposits in existence etc.

But more importantly he misses the mechanism which Tobin highlighted in his 1963 paper in which non-bank financials can compete with banks in the loan markets by taking away some borrowers and this leading to a fall in deposits. And this way, it is important not only for a single bank but for the banking system to induce depositors to bank with them.

Another thing which Post-Keynesians (some, not all of course) sometimes do is to think erroneously that bank borrowing (for purchases of goods and services at any rate) adds to demand and that non-bank borrowing/lending is demand-neutral and reading Keen’s post it seems he is close to saying something of the sort. And in his models, borrowing for purchases of financial assets also adds to “aggregate demand”.

I had written the following and am repeating it again about how a non-bank induces a borrower to borrow from it (who then extinguishes his loan from banks to become a borrower from the non-bank financial) and how this reduces the banking system’s balance sheet and hence deposits in the process – something Keen can’t see.

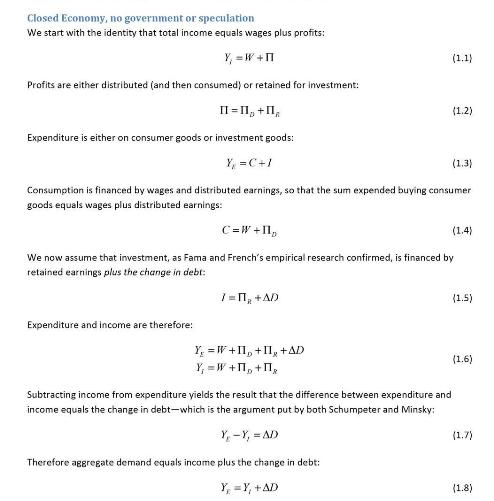

The following example is given in Tobin’s 1963 paper with my own numbers.

Start with a bank with initial balance sheet of 100 units. I will neglect capital and other liabilities to keep things clean so if you are not comfortable you can always change the liabilities side by reducing deposits by say 10 and replacing it with other liabilities. Also I call NBFIs’ liabilities “shares” and this is more like money-market mutual fund shares and shouldn’t be confused with stock-market shares.

t = 0

Banks

Assets: Loans = 100

Liabilities: Deposits = 100

Non-Financial Private Sector

Assets: Deposits = 100

Liabilities: Loans = 100

Non-bank Financial Institutions

Assets: Deposits = 0

Liabilities: Shares = 0

t = 1

At t = 1, let us say NBFIs attract 10 units of deposits from bank depositors. So the balance sheets will look like:

Banks

Assets: Loans = 100

Liabilities: Deposits = 100

Non-Financial Private Sector

Assets: Deposits = 90, Shares = 10

Liabilities: Loans = 100

Non-bank Financial Institutions

Assets: Deposits = 10

Liabilities: Shares = 10

t = 2

At t = 2, someone extinguishes his/her/its loan to the banking system by 10 unit. So,

Banks

Assets: Loans = 90

Liabilities: Deposits = 90

Non-Financial Private Sector

Assets: Deposits = 80, Shares = 10

Liabilities: Loans = 90

Non-bank Financial Institutions

Assets: Deposits = 10

Liabilities: Shares = 10

t = 3

At t = 3, someone borrows 10 units from NBFIs. So,

Banks

Assets: Loans = 90

Liabilities: Deposits = 90

Non-Financial Private Sector

Assets: Deposits = 90, Shares = 10

Liabilities: Loans = 100

Non-bank Financial Institutions

Assets: Loans = 10

Liabilities: Shares = 10

NBFIs who had 10 units of deposits no longer have it because they have lent 10 units which involves transfer of deposits. The net result at the end is that banks have lost a share lending of 10 units out of the initial 100 to non-banks and also deposits worth 10 units.

This of course can go on and it is in the interest of banks to prevent this from happening and induce the public to bank with them. In Tobin’s asset allocation theory, asset demands are dependent on the portfolio preference parameter and also the interest rate paid on the asset (or expected returns in general). So putting up interest rates on deposits would partly prevent this shift to non-bank financial intermediaries.

So in trying to show something, Keen’s effort turns counter-productive because his claim:

The only way for money not to be held in a bank is for it to be converted into some other kind of asset that is not a bank liability first.

turns out to be wrong and misleading.

He misses out Tobin’s insight that banks individually and collectively have to induce the non-banking public to hold deposits with them in his 1963 paper which the simple “loans create deposits” phrase does not highlight and how the banking system’s deposits can reduce due to competition from non-bank financials.

Plus there are more Tobinesque mechanisms (via his asset allocation theory) as I highlight in my previous posts James Tobin, Banking And The Widow’s Cruse and Holier Than Tobin? in which price changes of financial assets leads to a change in the stock of money which Keen is not aware of.

Instead his post has basic errors in monetary economics.