At an event commemorating the 100th anniversary of Nelson Mandela’s birth, Barack Obama provided a good explanation and context to understand politics around the globe in recent times. You don’t have to agree with his neoliberal ideology to appreciate what he said and how his fans or liberals in general dogmatically oppose the fact that free trade and globalisation have contributed to misery even in advanced nations.

It should make us hopeful. But if we cannot deny the very real strides that our world has made since that moment when Madiba took those steps out of confinement, we also have to recognize all the ways that the international order has fallen short of its promise. In fact, it is in part because of the failures of governments and powerful elites to squarely address the shortcomings and contradictions of this international order that we now see much of the world threatening to return to an older, a more dangerous, a more brutal way of doing business.

So we have to start by admitting that whatever laws may have existed on the books, whatever wonderful pronouncements existed in constitutions, whatever nice words were spoken during these last several decades at international conferences or in the halls of the United Nations, the previous structures of privilege and power and injustice and exploitation never completely went away. They were never fully dislodged. Caste differences still impact the life chances of people on the Indian subcontinent. Ethnic and religious differences still determine who gets opportunity from the Central Europe to the Gulf. It is a plain fact that racial discrimination still exists in both the United States and South Africa.

And it is also a fact that the accumulated disadvantages of years of institutionalized oppression have created yawning disparities in income, and in wealth, and in education, and in health, in personal safety, in access to credit. Women and girls around the world continue to be blocked from positions of power and authority. They continue to be prevented from getting a basic education. They are disproportionately victimized by violence and abuse. They’re still paid less than men for doing the same work. That’s still happening. Economic opportunity, for all the magnificence of the global economy, all the shining skyscrapers that have transformed the landscape around the world, entire neighborhoods, entire cities, entire regions, entire nations have been bypassed.

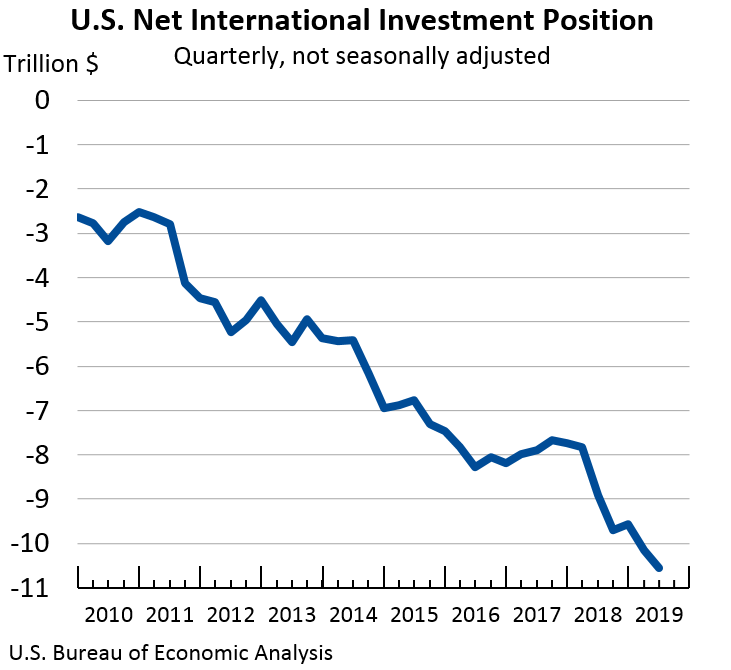

In other words, for far too many people, the more things have changed, the more things stayed the same. And while globalization and technology have opened up new opportunities, have driven remarkable economic growth in previously struggling parts of the world, globalization has also upended the agricultural and manufacturing sectors in many countries. It’s also greatly reduced the demand for certain workers, has helped weaken unions and labor’s bargaining power. It’s made it easier for capital to avoid tax laws and the regulations of nation-states — can just move billions, trillions of dollars with a tap of a computer key.

And the result of all these trends has been an explosion in economic inequality. It’s meant that a few dozen individuals control the same amount of wealth as the poorest half of humanity. That’s not an exaggeration, that’s a statistic. Think about that. In many middle-income and developing countries, new wealth has just tracked the old bad deal that people got because it reinforced or even compounded existing patterns of inequality, the only difference is it created even greater opportunities for corruption on an epic scale.

And for once solidly middle-class families in advanced economies like the United States, these trends have meant greater economic insecurity, especially for those who don’t have specialized skills, people who were in manufacturing, people working in factories, people working on farms. In every country, just about, the disproportionate economic clout of those at the top has provided these individuals with wildly disproportionate influence on their countries’ political life and on its media; on what policies are pursued and whose interests end up being ignored.

Now, it should be noted that this new international elite, the professional class that supports them, differs in important respects from the ruling aristocracies of old. It includes many who are self-made. It includes champions of meritocracy. And although still mostly white and male, as a group they reflect a diversity of nationalities and ethnicities that would have not existed a hundred years ago. A decent percentage consider themselves liberal in their politics, modern and cosmopolitan in their outlook.

Unburdened by parochialism, or nationalism, or overt racial prejudice or strong religious sentiment, they are equally comfortable in New York or London or Shanghai or Nairobi or Buenos Aires, or Johannesburg. Many are sincere and effective in their philanthropy. Some of them count Nelson Mandela among their heroes. Some even supported Barack Obama for the presidency of the United States, and by virtue of my status as a former head of state, some of them consider me as an honorary member of the club. And I get invited to these fancy things, you know? They’ll fly me out.

But what’s nevertheless true is that in their business dealings, many titans of industry and finance are increasingly detached from any single locale or nation-state, and they live lives more and more insulated from the struggles of ordinary people in their countries of origin. And their decisions — their decisions to shut down a manufacturing plant, or to try to minimize their tax bill by shifting profits to a tax haven with the help of high-priced accountants or lawyers, or their decision to take advantage of lower-cost immigrant labor, or their decision to pay a bribe — are often done without malice; it’s just a rational response, they consider, to the demands of their balance sheets and their shareholders and competitive pressures.

But too often, these decisions are also made without reference to notions of human solidarity — or a ground-level understanding of the consequences that will be felt by particular people in particular communities by the decisions that are made. And from their board rooms or retreats, global decision makers don’t get a chance to see sometimes the pain in the faces of laid-off workers. Their kids don’t suffer when cuts in public education and health care result as a consequence of a reduced tax base because of tax avoidance. They can’t hear the resentment of an older tradesman when he complains that a newcomer doesn’t speak his language on a job site where he once worked. They’re less subject to the discomfort and the displacement that some of their countrymen may feel as globalization scrambles not only existing economic arrangements, but traditional social and religious mores.

Which is why, at the end of the 20th century, while some Western commentators were declaring the end of history and the inevitable triumph of liberal democracy and the virtues of the global supply chain, so many missed signs of a brewing backlash — a backlash that arrived in so many forms. It announced itself most violently with 9/11 and the emergence of transnational terrorist networks, fueled by an ideology that perverted one of the world’s great religions and asserted a struggle not just between Islam and the West but between Islam and modernity, and an ill-advised U.S. invasion of Iraq didn’t help, accelerating a sectarian conflict.

Russia, already humiliated by its reduced influence since the collapse of the Soviet Union, feeling threatened by democratic movements along its borders, suddenly started reasserting authoritarian control and in some cases meddling with its neighbors. China, emboldened by its economic success, started bristling against criticism of its human rights record; it framed the promotion of universal values as nothing more than foreign meddling, imperialism under a new name.

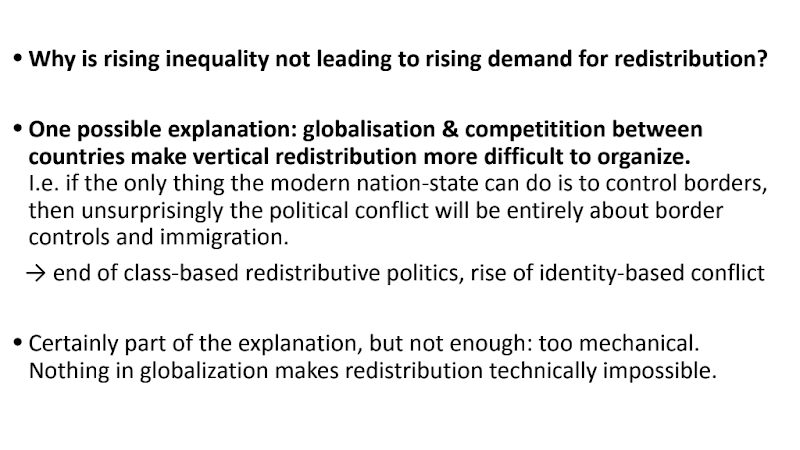

Within the United States, within the European Union, challenges to globalization first came from the left but then came more forcefully from the right, as you started seeing populist movements — which, by the way, are often cynically funded by right-wing billionaires intent on reducing government constraints on their business interests — these movements tapped the unease that was felt by many people who lived outside of the urban cores; fears that economic security was slipping away, that their social status and privileges were eroding, that their cultural identities were being threatened by outsiders, somebody that didn’t look like them or sound like them or pray as they did.

And perhaps more than anything else, the devastating impact of the 2008 financial crisis, in which the reckless behavior of financial elites resulted in years of hardship for ordinary people all around the world, made all the previous assurances of experts ring hollow — all those assurances that somehow financial regulators knew what they were doing, that somebody was minding the store, that global economic integration was an unadulterated good. Because of the actions taken by governments during and after that crisis, including, I should add, by aggressive steps by my administration, the global economy has now returned to healthy growth.

But the credibility of the international system, the faith in experts in places like Washington or Brussels, all that had taken a blow. And a politics of fear and resentment and retrenchment began to appear, and that kind of politics is now on the move. It’s on the move at a pace that would have seemed unimaginable just a few years ago. I am not being alarmist, I am simply stating the facts.