Let us think of a closed economy. Assuming – every year the government runs a budget deficit – a careless analysis would imply the public debt keeps rising relative to gdp.

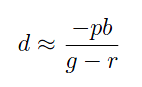

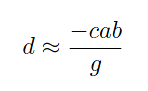

Without going into derivation – which you can find in other sources – it can be shown that if there is a growth rate of g, the public debt converges to

GD/Y = (PDEF/Y)/(g – r)

where GD is the government debt, Y – the national income, PDEF – the primary government deficit (government expenditure excluding interest payments less tax revenues) and g and r are the nominal growth rates and the interest rate respectively.

Several things. The above assumes – implicitly – that DEF is a constant percent of GDP (Y). Second, it neglects the fact that interest income is also income to bond holders which leads to more consumption. Third, less importantly, it ignores taxes on interest income. The first one is important. There is an implicit assumption of the exogeneity of the budget deficit and the above expression has nothing to say about the private sector’s propensity to save, consume etc.

The above expression has been derived using the assumption that g > r and summing a series. For the opposite case, the series used to derive it diverges. [For example, the equation

1 + x + x2 + x3 + … = 1/(1 – x)

is valid only if x < 1. For x > 1, the left hand side diverges and not negative as the formula implies!]

This has led authors to argue that if the growth rate is higher than the average interest rate paid on government debt, then the public debt doesn’t rise forever.

This intuition is not so right – although there is an element of truth in it but needs to be used extremely carefully.

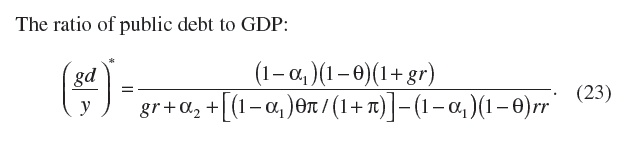

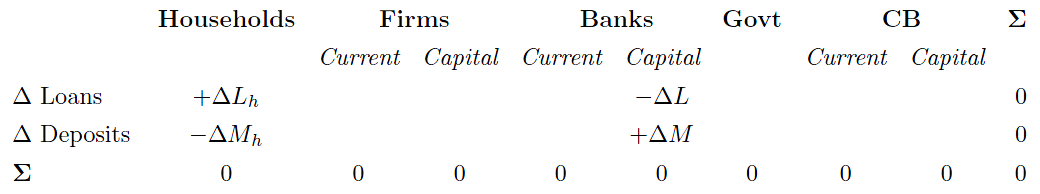

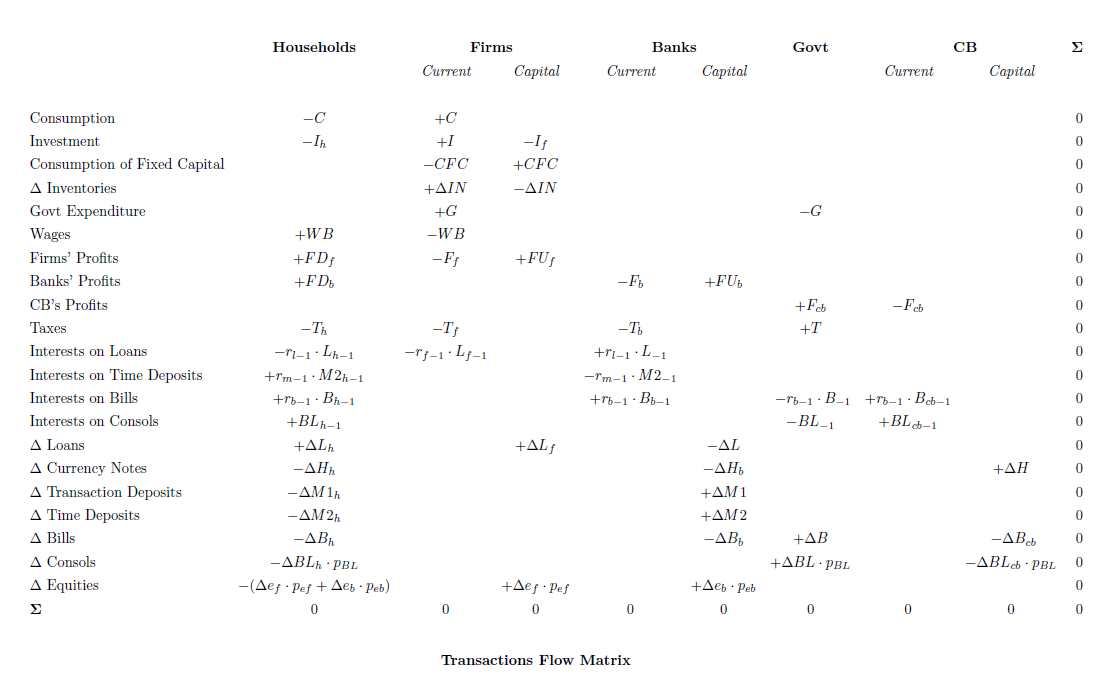

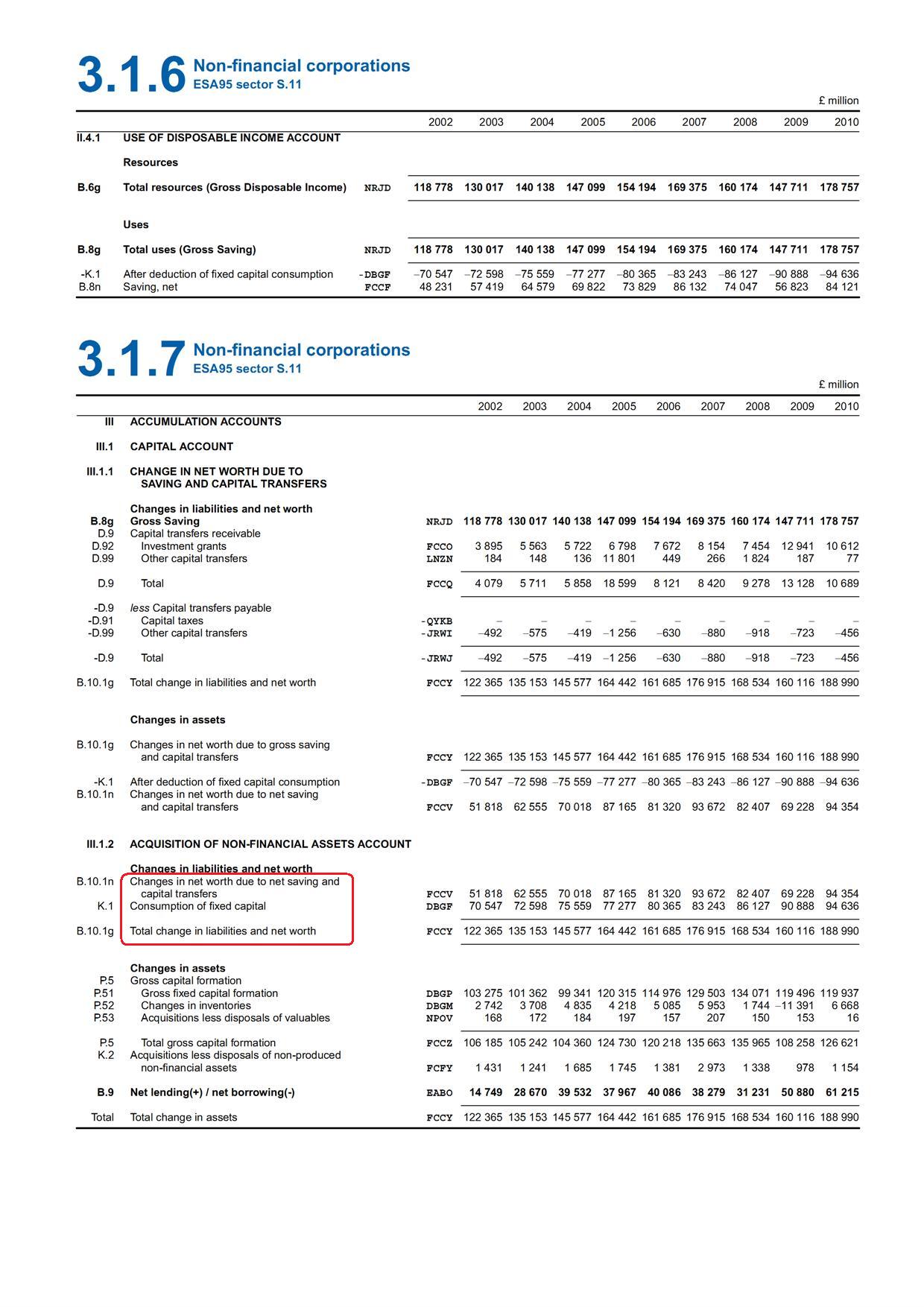

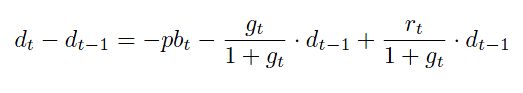

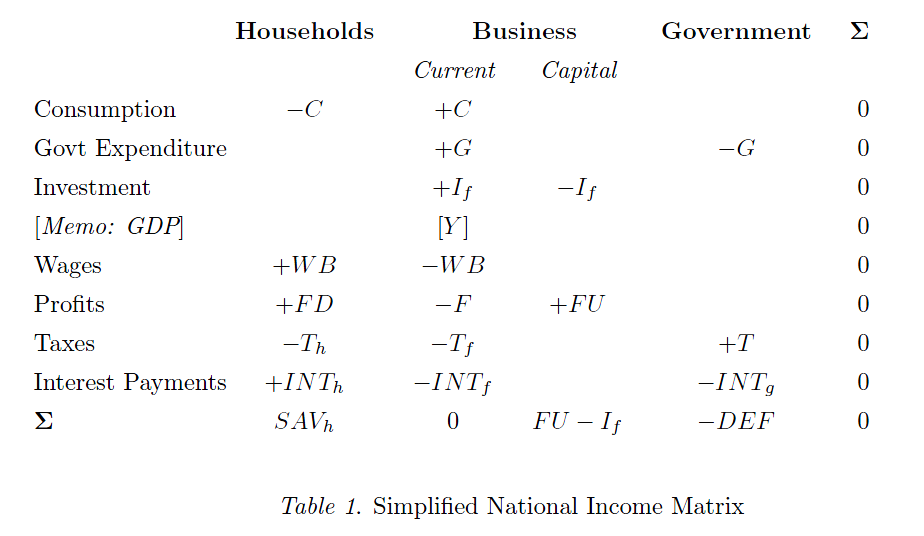

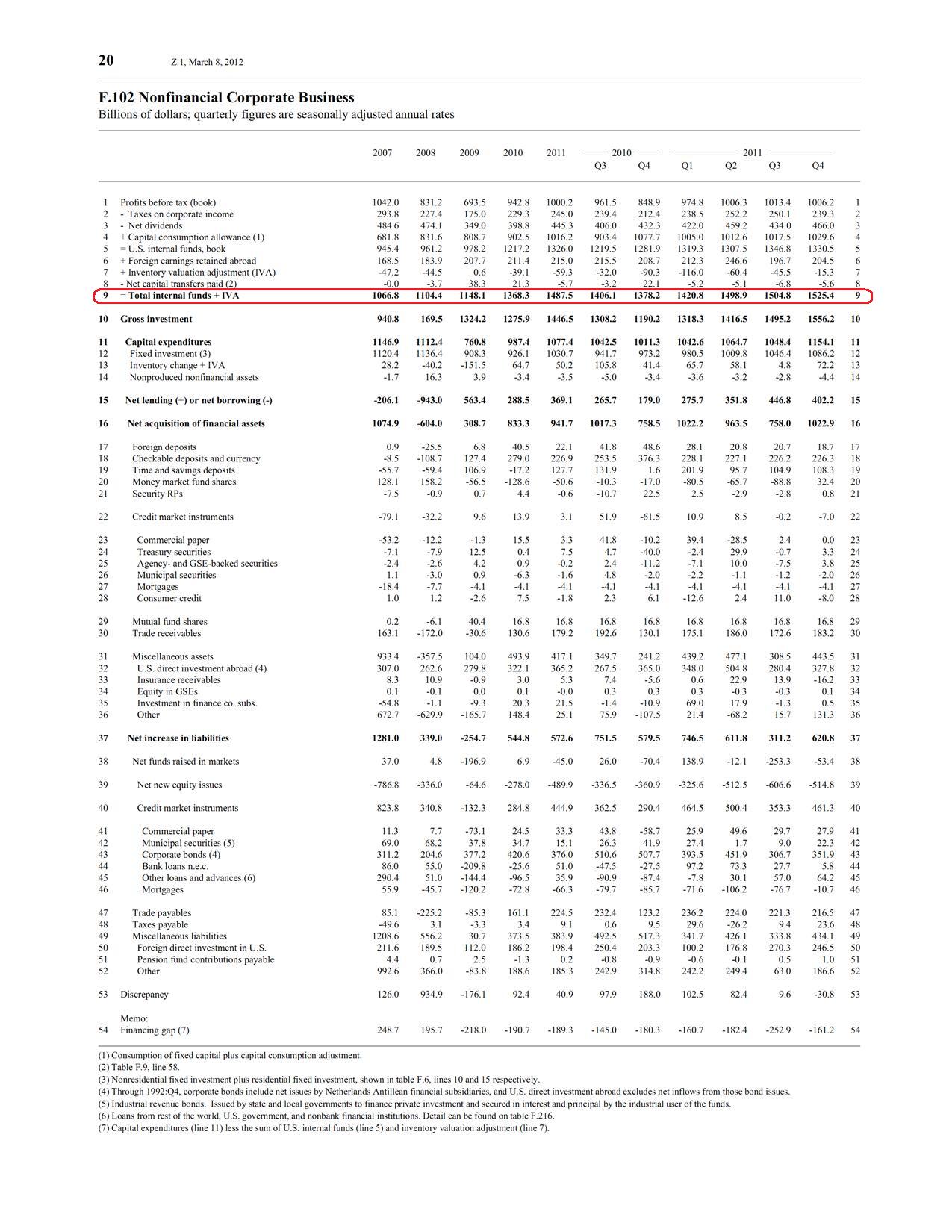

Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie [1] (but also [2] – which I haven’t managed to get hold of) show what this “stock-flow norm” converges asymptotically in the case of a very simple model of a closed economy – even when the government is not targeting a primary surplus in the budget. The following are from their paper and the lower case is used to denote real variables instead of nominal:

In the above gd is the real government debt, y is the real national income, α1 is the propensity of households to consume out of disposable income, α2 is the propensity to consume out of wealth, gr is the growth rate of output, rr is the real interest rate, π is the rate of inflation and θ is the tax rate.

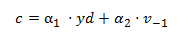

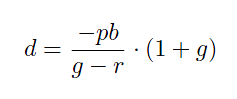

The assumed consumption function is:

where c is real consumption, yd is household real disposable income, and v is real household wealth.

This expression gives some intuition. The growth rate can be quite less than the interest rate and yet the public debt can be bounded. This is because bond interest payments by the government is income for bond holders. More importantly, the denominator contains α2 which significantly brings the (public debt/gdp) ratio down (compared to the case where α2 is zero).

Looking at the model and how the variables change, one can conclude that the government needn’t pursue a policy of targeting a primary surplus, contrary to the intuition neoclassical economists obtain by doing debt sustainability analysis. The budget may reach a primary surplus automatically as a result of higher taxes due to higher activity.

Also, there is no condition “g > r”.

One may wonder what value the parameter α2 has for various economies. According to Lance Taylor – a reviewer of Wynne Godley’s work [3] – the value could be 0.04 or 4% from econometric studies but he does notice the tendency of G&L to choose a higher value in pedagogic examples.

In my opinion it is higher. I think it’s a good challenge to try to show this empirically. This may be true because (abstracting out the effect of the external sector, the public debt ratio is better explained and also that a high α2 implies a quick response to a fiscal expansion – which is true.

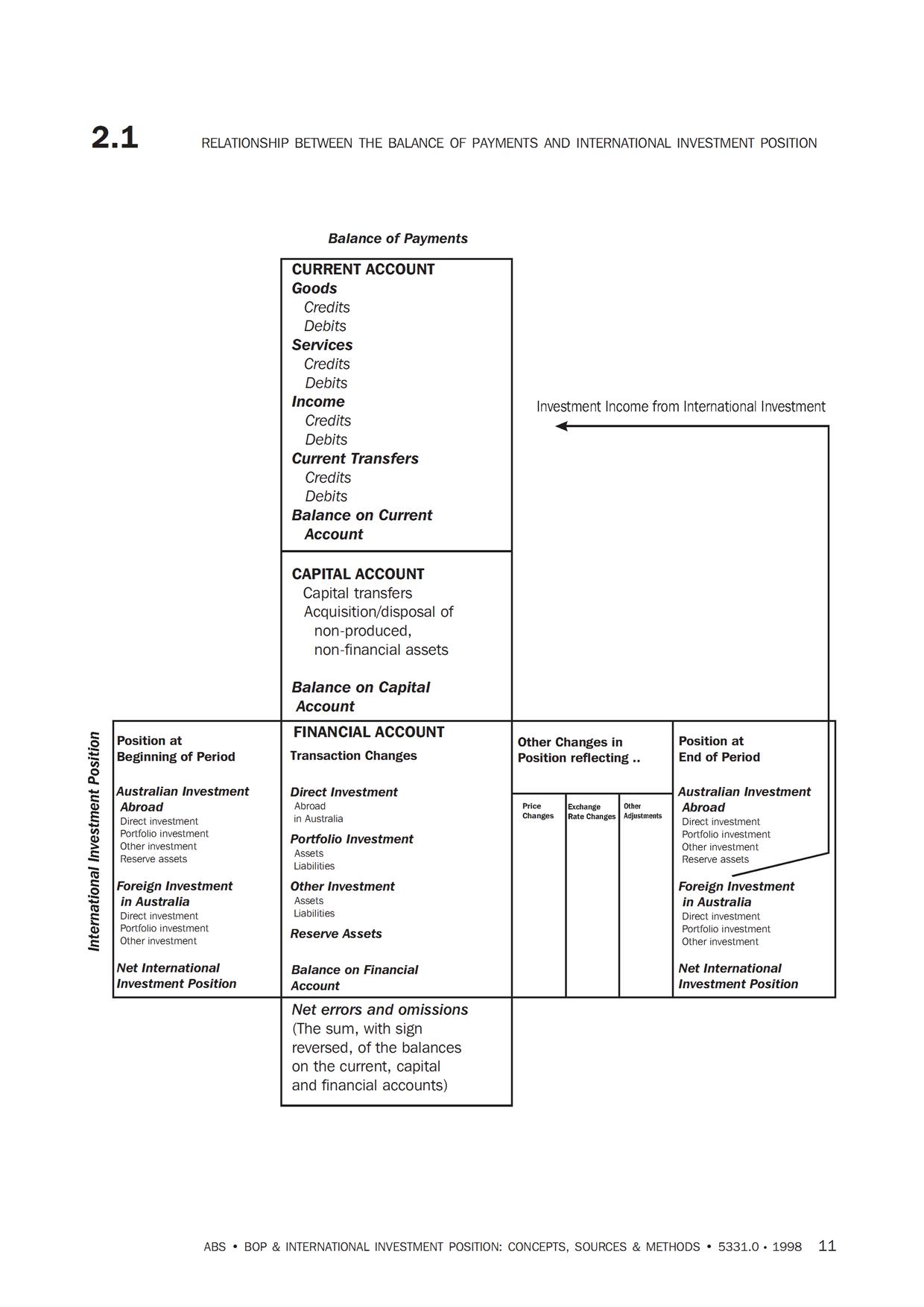

One should be highly careful about debt sustainability analysis. For the case of an open economy, while it is true that a debtor nation can be a debtor forever under some assumptions, achieving a faster growth in a world of free trade can lead to stock/flow ratios rising forever instead of converging. Which is to say that nations are balance-of-payments constrained.

References

- Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie, Fiscal Policy In A Stock-Flow Consistent Model, p 79, Journal of Post Keynesian Economics / Fall 2007, Vol. 30, No. 1. Draft version available at http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/?docid=911

- Wynne Godley and Bob Rowthorn, Appendix; The Dynamics Of Public Sector Deficit And Debt, in J. Michie and J. Grieve Smith (eds), Unemployment in Europe (London: Academic Press), pp. 199-206.

- Lance Taylor, A Foxy Hedgehog: Wynne Godley And Macroeconomic Modelling, Camb. J. Econ. (2008) 32 (4):639-663.