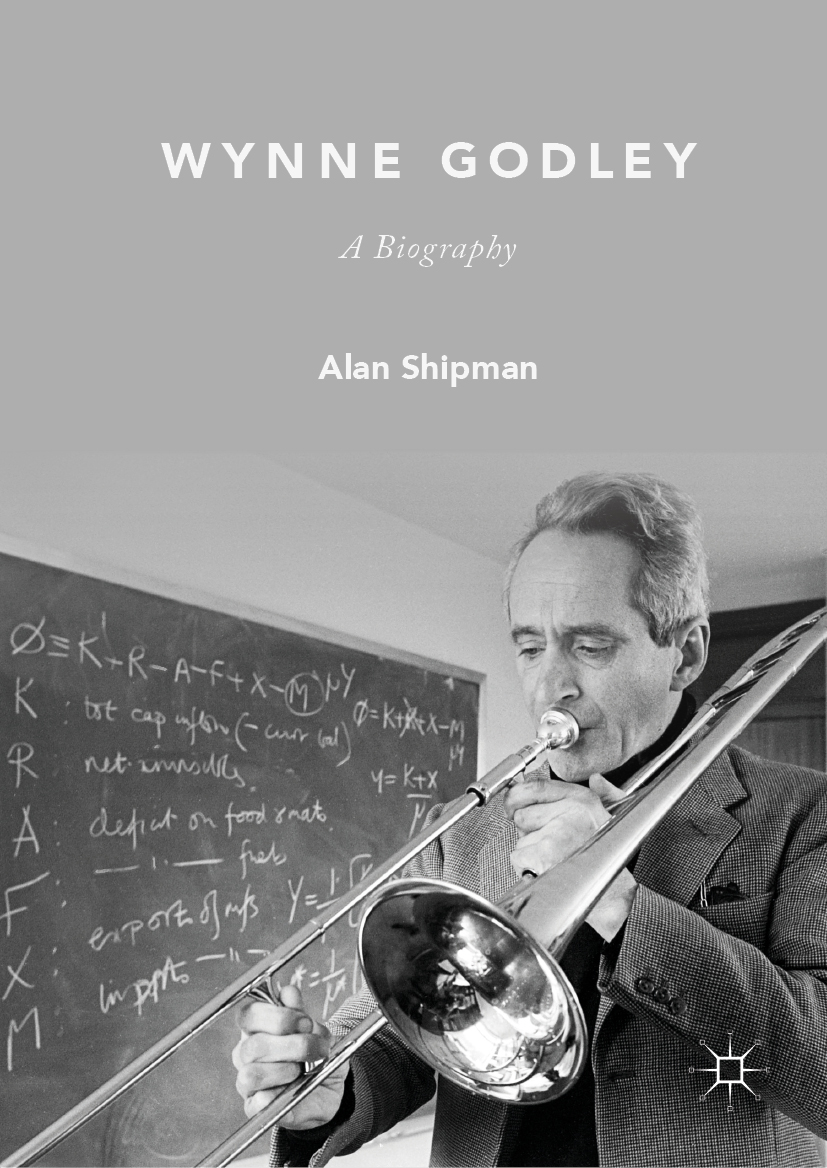

From Alan Shipman’s biography, Wynne Godley, A Biography, Chapter 9: Balance Of Payments, Deindustrialisation And Protection, page 151:

Of all Godley’s policy prescriptions, direct import controls were the one most roundly rejected by other economists, and least likely to be adopted by politicians with any chance of gaining power. The accusation of advocating a policy that was economically illogical, politically infeasible and inadmissible in international law hurt deeply, but never crushed his belief that import quotas should be seriously considered as an additional macroeconomic instrument. The depth of the wound emerged in an unusually personal statement to a 1978 conference on ‘Slow Growth in Britain’, convened by Oxford University’s Wilfred Beckerman in Bath. ‘I am disconcerted and distressed to find myself, together with the group of people with whom I work in Cambridge, in such an isolated position. For we seem to be the only group of professional economists who entertain the possibility that control of international trade may be the only way of recovering and maintaining the prosperity of this country; that free trade may be an enemy for the relatively weak’ (Godley 1979: 226).

…

References

…

Godley, W. (1979). Britain’s chronic recession—Can anything be done? In W. Beckerman (Ed.), Slow Growth in Britain. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Keynes said that:

A study of the history of opinion is a necessary preliminary to the emancipation of the mind.

Although in the poor countries, ones colonised and which suffered because of imposition of laissez-faire, there have been a lot of opposition to free trade—and those voices aren’t heard through silencing internationally—in the advanced countries, it has been almost non-existent except from Cambridge Keynesians and maybe a few others. In recent times, we see some opposition, but not remotely like this even 40 years ago. It is important to know the history of thought to understand how hegemonic the ruling ideology has been.

For Wynne Godley, dissenting against free trade was one of the most important reasons for his dissent against the profession. In his short autobiography written in 2001 for A Biographical Dictionary Of Dissenting Economists, Godley said:

There are two aspects (in particular) of the work of the CEPG [Cambridge Economic Policy Group] which put its members into a category which may he termed ‘dissenting’. The first – a matter mainly of concern to the modelling fraternity and academic econometricians – was the unconventional view we took about how to construct and use an econometric model.

…

The second, and more egregious, respect in which we became a ‘dissident’ group was that, as a result of trying to think through the possible ways in which Britain’s net export demand might be improved, we entertained the possibility that international trade should be, in some sense, ‘managed’. There might, we argued, be no way in which the adverse trends could be reversed other than some form of control of imports. Our argument (see for instance Cripps, 1978; Cripps and Godley, 1978) was never one in favour of protectionism as normally understood – that is, the selective and unilateral protection of relatively failing industries under conditions of general stagnation. On the contrary, we were most careful to lay down conditions under which the management of trade would benefit not only our own country (without making its industry less efficient) but would also increase the level of trade and output in the rest of the world. The two basic principles were, first, that trade management should reduce import propensities without ever reducing imports themselves (in total) below what they otherwise would have been; and, second, that ‘protection’ should be as minimally selective as possible (for example, through the use of market mechanisms such as auction quotas) so that industrial inefficiency would not be sponsored.

I was surprised by the hostility with which our ideas about trade were received. It seemed to me at the time, and still seems to me, that the arguments actually used against us (at their most coherent by Maurice Scott et al., 1980) did not, in practice, rest on a well-articulated theoretical position but on very special assumptions about behavioural relationships and international political responses. (I have, to the best of my ability, answered these particular points in Christodoulakis and Godley, 1987.)

…

The ‘dissident’ argument in favour of managed trade is well summarized in Kaldor (1980), where he points out that the modern theory of international trade is based on the assumption that all production takes place according to the conditions described by the neoclassical production function, with constant returns to scale. Kaldor postulated instead, and he was surely right to do so, that the principle of circular and cumulative causation leads (through dynamically increasing returns) to a process, not of convergence, but of polarization between successful and unsuccessful economies in which success in competitive performance feeds on itself and losers become immiserated by trade.

…

Godley’s Major Writings

…

(1978), ‘Control of Imports as a Means to Full Employment: The UK’s Case’ (with T.F.

Cripps), Cambridge Journal of Economics, 2, September.…

(1987), ‘A Dynamic Model for the Analysis of Trade Policy Options’ (with N. Christodoulakis), Journal of Policy Modelling, 9.

…

Other References

Cripps, T.F. (1978), ‘Causes of Growth and Recession in World Trade’, Cambridge Economic Policy Review, No. 4.

Kaldor, N. (1980), ‘The Foundations of Free Trade Theory and Recent Experiences’, in E. Malinvaud and Fitoussi, J.P. (eds), Unemployment in Western Countries, London: Macmillan.

…

Scott, M., Corden, W.M. and Little, I.M.D. (1980), The Case Against Import Controls (Thames Essay No. 24), London: Trade Policy Research Centre.

…