The financial and non-financial resources at the disposal of an institutional unit or sector shown in the balance sheet provide an indicator of economic status. These resources are summarized in the balancing item, net worth. Net worth is defined as the value of all the assets owned by an institutional unit or sector less the value of all its outstanding liabilities. For the economy as a whole, the balance sheet shows the sum of non-financial assets and net claims on the rest of the world. This sum is often referred to as national wealth.

– 13.4, System of National Accounts 2008 (pdf)

Recently, Paul De Grauwe joined the long debate on TARGET2 with a paper What Germany Should Fear Most Is Its Own Fear: An Analysis Of Target2 And Current Account Imbalances. He is supposed to be the top economist in both public and academic debates about the Euro Area but unfortunately, there are glaring errors in his paper.

This paper was aimed at Hans-Werner Sinn who started ringing alarm bells on the huge TARGET2 claims of the Deutsche Bundesbank. The claim of this post (and some more in the past in this blog) is that while Prof Sinn may be wrong on many issues in the debate, he is right about a few important issues. Needless to say, his prescriptions are not defended by me. I am a fan of Nicholas Kaldor’s ideas as quoted in my post Nicholas Kaldor On The Common Market.

De Grauwe’s argument is slightly more nuanced that others such as Karl Whelan. While Whelan dismisses any argument that a loss of creditor nations’ TARGET2 claims on the periphery Euro Area nations is a loss, De Grauwe modifies this to say that the repatriation of funds by Germans (individual investors and institutions) does not increase Germany’s risks.

So we have this claim in his paper:

Thus the increase in the Target2 claims of the Bundesbank should not be interpreted as an increase of foreign claims of Germany, and thus as an increase of risk from higher foreign exposure. Using the Target claims as a measure of risk incurred by the German population is therefore erroneous. As we have seen earlier, after 2010, the Target claims of Germany (and other Northern countries) increased dramatically and much more than the current account surpluses during this period. This increase in Target2 claims cannot be interpreted as an increase in the foreign exposure (net foreign claims) of Germany, except to the extent that they were the result of current account surpluses. What changed dramatically is the nature of these claims. Prior to 2010, these claims were mainly claims held by private German agents (mainly financial institutions). Similarly the liabilities of the peripheral countries were held by private agents (financial institutions). The eurozone crisis led to a dramatic shift. As a result of the breakdown of the interbank market, a large part of these private claims and liabilities were transformed into (public) Target claims and liabilities (Buiter et al., 2011), without however changing the total net foreign claims and liabilities of these countries. Thus, the explosion of the Target claims of Germany since 2010 cannot be interpreted as an explosion of the risk of foreign exposure for Germany.

Ignoring the fact that the repatriation of funds by German residents back to Germany puts the risks on the public sector’s books and awards the (ex-) German lender, there is some element of truth to the above claim. The repatriation of funds does not increase Germany’s gross international investment position (assets and liabilities) but just changes the composition. It however ignores the fact that nonresidents also reallocate their portfolios in German assets and this increases Germany’s gross foreign assets and liabilities and in case there is a default by the periphery on the TARGET2 liabilities (in case they leave the Euro Area), Germany suffers a loss. We will see this with an example below. Before that let me highlight one misleading claim in the paper:

The value of the money base is exclusively determined by its purchasing power in terms of goods and services. This value is independent of the value of the assets held by the central bank. In fact in the fiat money system we live in, the central bank could literally destroy the assets without any effect on the value of the money base. In order to stabilize the value of the money base, the central bank should keep the right supply of money base, i.e. a supply that will maintain price stability.

That is Monetarist handwaving. Won’t say anything further!

When the central bank acquires assets, mainly government bonds, it issues new liabilities. The latter take the place of the government bonds in the portfolios of private agents. It is as if the government debt has disappeared. It has been replaced by central bank debt. The central bank could literally put the government bonds in the shredding machine. This would not affect the value of the central bank debt as the central bank has made no promise to redeem its debt (money base) into government bonds. And as long as the central bank maintains price stability, agents will willingly hold the new debt (money base) issued by the central bank.

That is incorrect. The People’s Bank of China cannot shred US Treasuries into a dustbin and claim it does not matter to the Chinese people.

Now to the main point about this post: foreigners shifting funds into assets issued by German residents.

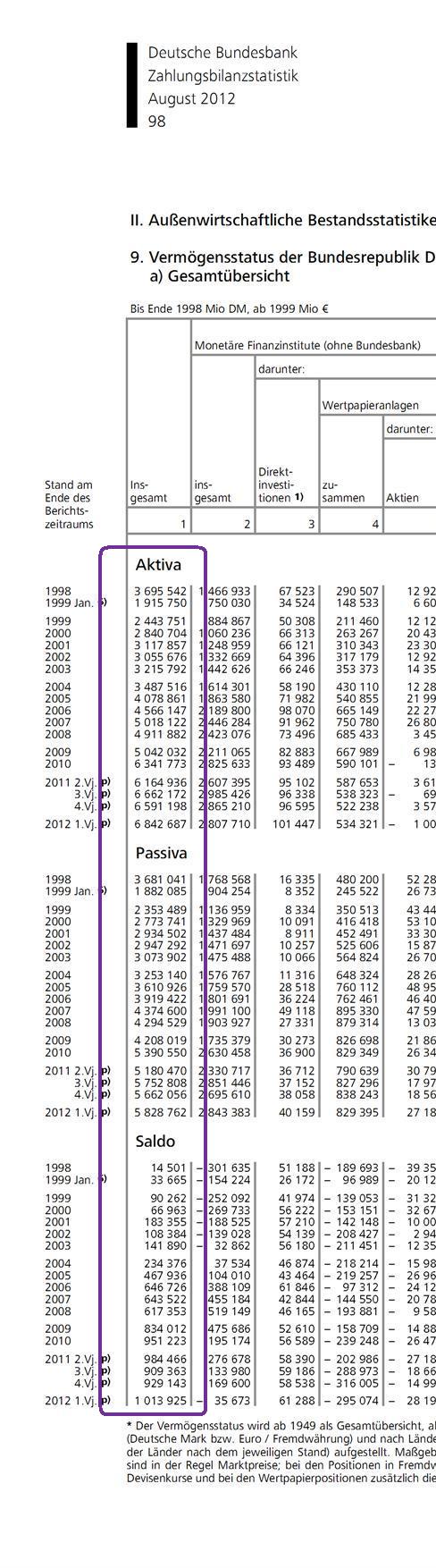

Here is from the Bundebank’s statistical supplement for Germany’s international investment position:

Aktiva is Assets, Passiva is Liabilities and Saldo is Net.

Germany’s assets and liabilities can increase as a result of a nonresident (such as from Spain) buying German Bunds (government bonds). If an institution in Spain liquidates its position in Spanish assets and transfers the funds to purchase Bunds, Bundebank’s TARGET2 claims will increase (in the current scenario).

Let us use these numbers to see how Germany’s IIP changes if there is a purchase of €100bn of German assets by German nonresidents (but residents in Euro Area for simplicity).

Initially,

Germany’s Assets = €6,843bn

(of which TARGET2 claims = €727bn)

Germany’s Liabilities = €5,829bn

NIIP = €1,014bn

Now assuming a nonresident purchases €100bn of German government bonds from a German resident,

Germany’s Assets = €6,943bn

(of which TARGET2 claims = €827bn)

Germany’s Liabilities = €5,929bn

NIIP = €1,014bn

So while Germany’s gross assets and liabilities have increased by €100bn, its net position is the same.

However this is not the end of the story. When nonresidents purchase €100bn worth of German securities, the TARGET2 claims of the Bundesbank (or more generally creditor nation’s TARGET2 claims) increases by €100bn. If there is breakup of the Euro Area position at this point in time, this will leave the creditor EA nations with an additional liability of €100bn (incurred just before the breakup) while at the same time losing the €100bn of assets (TARGET2) acquired (in addition to other assets) and hence an NIIP worse than the case if the transaction had not occurred.

This number can be much higher because when there are tensions building up in the financial markets, foreigners may shift funds into Germany and if a breakup really is forced upon the Euro Area, it will leave Germany with additional liabilities and a lower NIIP than before and a huge loss of wealth.

At any rate, a non-negligible part of the German international investment position can be due to foreigners already having shifted funds in German assets (as the gross assets and liabilities position indicates).

But De Grauwe claims (thanks to JKH for pointing):

It is surprising that these simple principles are not widely understood.

!

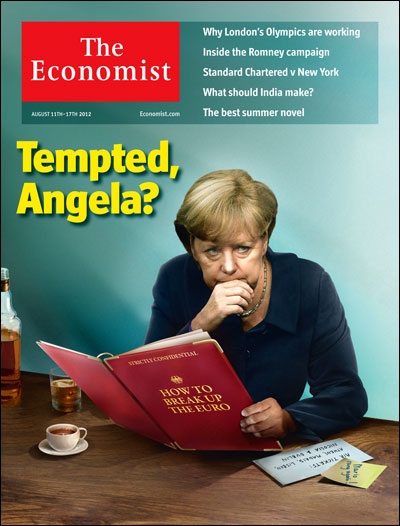

Recently, the ECB announced a plan which substantially reduces the risks of a breakup of the Euro Area. In the absence of a breakup, discussions such as these are purely academic. However, the story has new twists and turns, and one can never be sure what is going to happen. It is however counterproductive to claim there is no risk/loss (in select scenarios) when there is indeed one.

Needless to say this analysis is not a defense of the German position either. Free trade has helped them a lot and it is time they increase domestic demand and help reduce global imbalances.