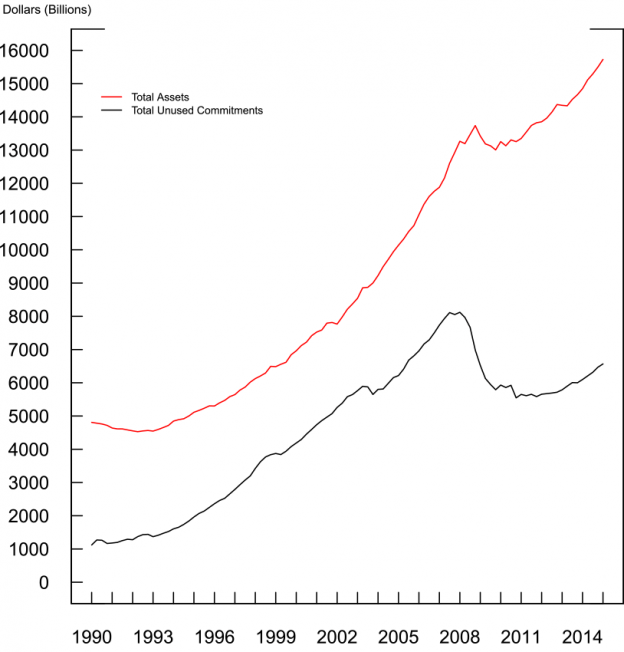

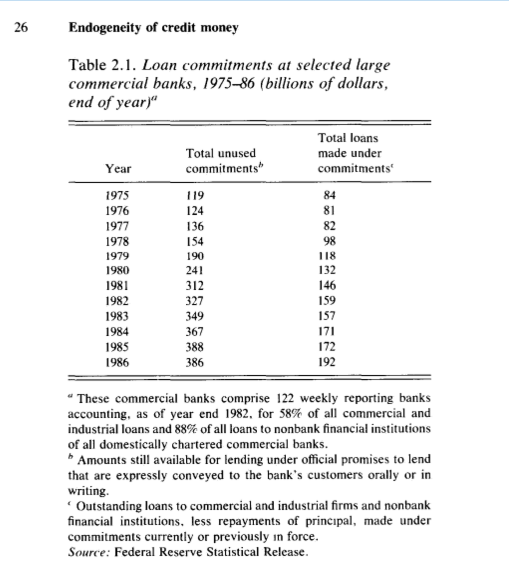

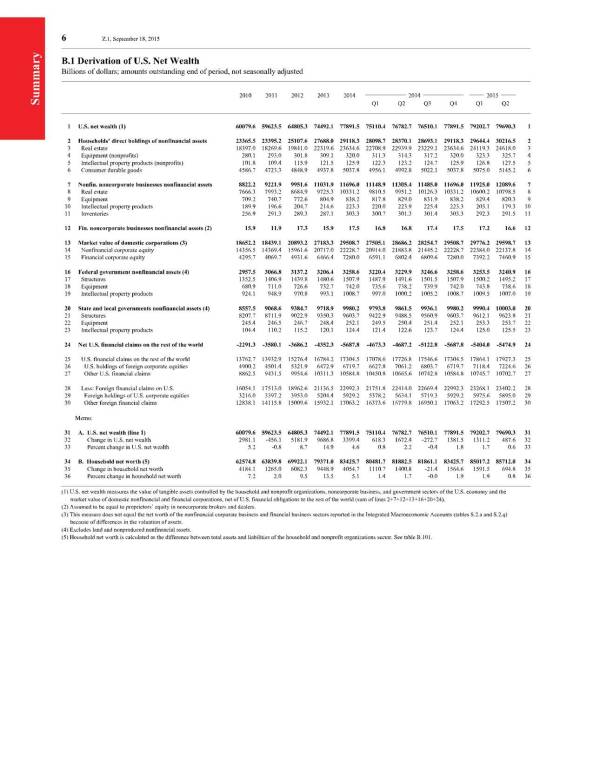

The latest release of the Federal Reserve Statistical Release Z.1, Financial Accounts of the United States – Flow of Funds, Balance Sheets and Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts or just “flow of funds” has a new table B.1: Derivation of U.S. Net Wealth.

According to the release:

A new table on the derivation of U.S. net wealth (table B.1) has been added to the summary section of the “Financial Accounts.” The calculation of U.S. net wealth includes the value of nonfinancial assets (real estate, equipment, intellectual property products, consumer durables, and inventories) held by households and nonprofit organizations and noncorporate businesses. For the federal government and state and local governments sectors, only structures, equipment, and intellectual property products are included; values for land and nonproduced nonfinancial assets are not available. The measure of U.S. net wealth also includes the market value of domestic nonfinancial and financial corporations, and is adjusted to reflect net U.S. financial claims on the rest of the world. This definition of U.S. net wealth differs from the sum of the net worth of sectors shown in the Integrated Macroeconomic Accounts (IMA). A forthcoming FEDS Note will provide additional information.

click to expand, and click again to zoom

According to it, the United States net wealth was $79.69 trillion.

It’s important to understand how this is reached. Normally we divide the world in various sectors: households, production firms, the financial sector, government and the rest of the world. In real life one adds more nuances to all this. So for example, in the table above, we have a sector “non-financial non-corporate businesses”.

Now, there are two types of assets: non-financial assets and financial assets. Non-financial assets are things such as houses, machines and so on. Financial assets are things such as currency notes, bonds, equity securities and so on.

In the system of national accounts (e.g., the 2008 SNA), all financial assets have a counterpart liability. So financial assets = liabilities for the world as a whole. It’s of course not true for a nation because assets and liabilities between residents and non-residents do not cancel out.

There is one complication, however: equity securities. The 2008 SNA treats equity securities as liabilities of corporations, just like debt securities. This is despite the fact that a company isn’t bound by law to pay dividends to holders of equity, unlike the case for debt securities or loans (for which interest is needed to be paid periodically and also the principal upon maturity).

All economic units have a net worth. This is the difference between assets and liabilities. So,

Assets = Liabilities + Net Worth.

Since equities are treated as liabilities in the 2008 SNA, the net worth of firms can in fact turn negative. This might happen if the price of equities is high.

So it is easy to derive the net worth of a nation. Resident economic units’ liabilities held by resident economic units cancel out and one is left with non-resident units’ liabilities to residents (i.e., resident units’ assets “held abroad”) and residents’ liabilities to non-residents. This is the net international investment position.

So, as per the 2008 SNA (and the Balance of Payments Manual, 6th Edition),

Net Worth of a nation = Non-financial assets held by residents + Net International Investment Position

The Federal Reserve however does not do the same for flow of funds. It does not treat equities as liabilities.

But one has to be careful about double counting. It’s easy to sum up non-financial assets of all economic units, such as as done by the SNA. But in the flow of funds, with the special treatment on equities, we shouldn’t use corporate businesses’ non-financial assets. If you read the explanation and see the table B.1 carefully, corporate businesses’ assets have not been added, only “non-corporate businesses'” non-financial assets have been added. Since equities are not treated as liabilities in the sense of debt securities, the market value of corporations is needed to be added. This is line 13 in Table B.1.

There is one complication however. Even though equities is not treated as liabilities, that held by foreigners is treated as liabilities. Otherwise, one can have a source of inconsistency. Suppose equities held by a non-resident economic units is not treated as liabilities. Suppose foreigners sell $1bn of equities and purchase T-bills with that. This will mean that the net wealth reduces. Which doesn’t make sense. Hence, one is forced to treat foreigners’ equity holdings as liabilities. So the foreign aspect of the whole calculation is the same as as done in the SNA and one needs to include the net international investment position of the United States which is line 24. (minus $5.47 trillion).

So that basically summarizes the calculation of the United States net wealth as per the Federal Reserve flow of funds report.

How does this compare with the SNA measurement? Some tables in the report are only updated to 2014. So let’s use those numbers.

Flow of funds’ net wealth for 2014 = $77.89 tn (Table B.1, line 1).

Now, go to Table S.2.a. These tables use SNA definitions. Add lines 76-81.

This gives us a value of $87.34 trillion.

However the Z.1 report has an error in the way SNA/IMA way of calculating net worth. Line 77 in Table S.2.a is incorrect. There’s double counting. It uses the SNA/IMA concept of net worth but instead calculates it using the FoF concept. One should subtract line 29 in table B.101 which is $10.04 trillion. Hence the US net worth in the SNA definition is $87.34 trillion minus $10.04 trillion which is $77.30 trillion.

So in short, the net worth of the United States as per the flow of funds definition at the end of 2014 was $77.89 trillion and according to the SNA/IMA it was $77.30 trillion.

What does all this mean? Hmm. Not to easy to answer, except saying that familiarity with the system of measurement helps in understanding how the economy works. Which measurement is better – the new table B.1 or S.2.a? Doesn’t matter.

I am thankful to commenters in this blog post by Steve Randy Waldman, especially JKH and Marko.

Part 2 here United States’ Net Wealth, Part 2