Adam Tooze’s book Crashed seems popular. The book and two reviews have some good appreciation of Wynne Godley’s work used in the book to explain why the crisis happened. The two reviews, both published in New Left Review:

- In The Crisis Cockpit, by Cédric Durand,

- Situationism À L’envers? by Perry Anderson.

In the acknowledgments section of his book Adam Tooze writes:

Wynne Godley was a mentor and teacher of a very different kind. Spontaneously warm and generous in spirit, he took me under his cape in my first year at King’s and introduced me, and a group of my contemporaries, to what was, at the time, a highly idiosyncratic brand of economics. In so doing he provided a model of intellectual warmth and vitality. He also confirmed doubts that had been gestating in me about the IS-LM model that was my first great love in economics. Wynne introduced me to the importance of looking “beyond the flows” and insisting on stock-flow consistency in macro models. I don’t think this book, written almost thirty years later would have been the same without his early influence.

Cédric Durand says:

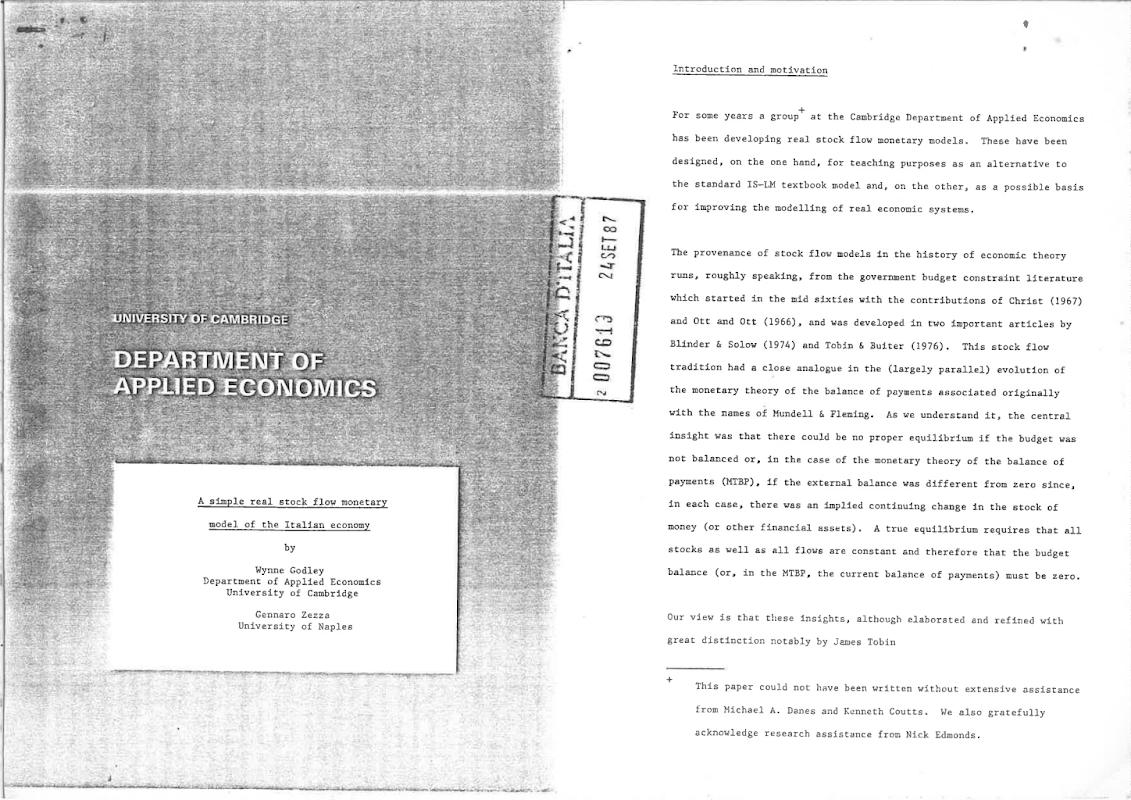

What, then, are the conceptual underpinnings of Tooze’s work? In Crashed, none are made explicit. Nevertheless, in his emphasis on balancesheet vulnerabilities he implicitly follows the lead of post-Keynesian research, one of the more creative currents in contemporary economics, deriving from a synthesis of Keynes with a specific form of Marxian macroeconomics pioneered in the 1940s by Michał Kalecki. Tooze appears to draw in part upon the post-Keynesian ‘stock-flow consistency’ model, an approach that seeks to combine the ‘real’ and financial spheres of the economy. The term ‘stockflow’ implies attentiveness to the build-up of vulnerabilities in the ‘stock’ of financial assets and liabilities, beyond the financial ‘flows’ themselves: for example, when a sector’s prolonged deficit results in an unsustainable stock of debt. This approach has become increasingly popular since the crash, and was incorporated in the Bank of England’s policy-making toolkit in 2016. Initially developed by Nicholas Kaldor in the 1940s, the methodology was transformed in the 1960s and 70s by the work of James Tobin and Wynne Godley, Tooze’s teacher at Cambridge. Godley is credited by Tooze here with introducing him to ‘the importance of looking “beyond the flows” and insisting on stock-flow consistency’.

At the heart of this approach is the idea that macroeconomic dynamics hinge on a three-way interaction between the financial balances of public, private and foreign sectors. This ‘three balances’ perspective arguably supplies the unstated backbone of Tooze’s general argument. His achievement is to dress the dryness of this technical skeleton with the dense and complex sensitivity of historical flesh. If this framework were to be made explicit, it would suggest that the adventures of the private-sector balance drove a spectacular upward distribution of wealth that ultimately backfired in the political arena as resurgent nationalism and xenophobia. Public-sector balances were the scene of dramatic deliberations about crisis-containment strategy, with central bankers standing far above the other actors in the hierarchy of policy-making. Finally, the international balance-sheet perspective sheds light on a multipolar world where monetary policy, currency reserves and financial sanctions can be as effective as military force in deciding geopolitical outcomes and national fates.

…

Tooze’s mentor Wynne Godley observed in 1992 that the establishment of a single currency on the Maastricht model ‘would bring to an end the sovereignty of its component nations’, leaving them with the economic autonomy of ‘a local authority or colony’, while no central government could emerge with sufficient fiscal muscle to take decisive economic action. As a result, in the case of a major macroeconomic shock, the populations of countries deprived of the power to devalue, and not benefiting from a system of fiscal equalization, will see ‘emigration as the only alternative to poverty’. This sounds like an impressive, prescient account of the role of macro-institutional systems—and not just bad policy-making, as Tooze would have it—in the fates the Greek, Portuguese and Spanish people have had to suffer. Political, geopolitical and economic dimensions are structurally intertwined via institutions in the process of crisis making and management. While Tooze perfectly demonstrates the latter, in particular in his magnificent account of the balance-sheet intricacy at the heart of the 2008 crisis, he doesn’t account for the former.

Perry Anderson:

Durand observes, its narrative is no simple—or rather in this case, of course, highly complex and intricate—empirical tracking of the crisis and its outcomes. It possesses definite ‘conceptual underpinnings’, suggested by Tooze himself in acknowledging his debt to Wynne Godley’s use of ‘stock-flow consistency’ modelling of the financial interactions between public, private and foreign sectors. This in Durand’s view supplies ‘the unstated backbone’ of Tooze’s general argument.

Both judgements appear sound. But in Durand’s exposition a paradox attaches to each of them, since by the end of his review, somewhat different notes are struck. For Godley, one of the key advantages of the stock-flow consistency approach was that it integrated the financial with the real economy, as alternative models did not. Durand, however, remarks that Crashed ‘does not discuss the concrete intertwining of the financial and productive sectors in the global economy at all’, and so ‘fails to set the financial crisis in the context of the structural crisis tendencies within contemporary capitalist economies.’ This observation in turn generates another, which might seem to put in question Durand’s overall tribute to the book. For there he writes of ‘Tooze’s unwillingness to investigate the relations between the political and the economic’, a reluctance that ‘ultimately undermines his account of the crisis decade.’ Logically, the question then arises: do these two apparent contradictions lie in Tooze’s work, or in Durand’s review of it? Or can both be coherent in their own terms?

So Adam Tooze is appreciated in using the correct mathematical formulation but not paying much attention to political economy. Of course Wynne Godley’s work is based with a background in Kaldorian/Post-Keynesian economics, so the critique doesn’t apply to him. Tooze has a preface to his response to Anderson which will appear soon.