There’s a new book, The Elgar Companion To John Maynard Keynes, edited by Robert W. Dimand, Harald Hagemann. Chapter 76 titled Nicholas Kaldor is written by Anthony Thirlwall.

Thirlwall reminds us of Kaldor’s dislike to enter the common market in the 70s:

The Labour Party lost power in 1970 and Kaldor had more time to campaign on two main public issues which concerned him greatly. The first was the acceptance by economists and policy-makers of the doctrine of monetarism which had spread with the virulence of a plague from the University of Chicago under the influence of Milton Friedman to infect policy thinking at the highest level in the UK. The second concerned the UK’s entry into the Common Market (now the European Union). With regard to monetarism, Kaldor led the intellectual assault worldwide against the monetarist view that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon in a causal sense caused by excessive government expenditure financed by money creation. On the contrary, argued Kaldor, because money consists largely of credit, and credit only comes into existence if it is demanded, money is endogenous to an economy not causal in the determination of output and prices. The major cause of inflation, at least in mature industrial countries, is rising wages and other costs. Kaldor could find no evidence in the UK. or across countries, of any relationship between the size of countries’ budget deficits and measures of broad money (Kaldor 1980c). Kaldor lost the battle against monetarism in the UK, but won the war because the doctrine of monetarism is now dead.

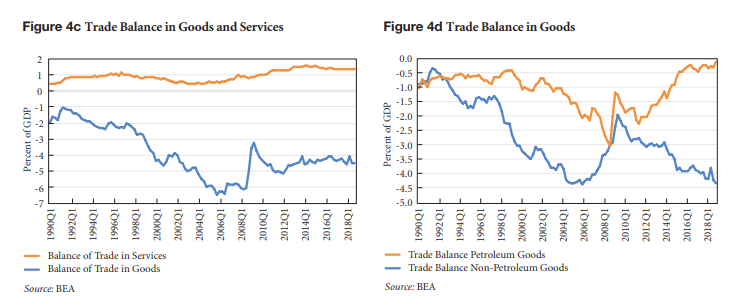

On the issue of the UK joining the Common Market. Kaldor was highly sceptical of the alleged dynamic benefits stemming from a larger market for the export of goods and services. He argued that because imports are likely to grow faster than exports, as trade barriers come down, the UK would need to deflate the economy to preserve balance of payments equilibrium, and this would slow growth. In addition to this, the budgetary contribution would be huge, the price of food would rise leading to wage increases and Britain would be letting down the Commonwealth countries which had a preferential access to the UK market. The vote in 1975 against joining the Common Market was lost, but Kaldor appears to have been correct in his predictions. The dynamic benefits of having become a member of the European Union are nowhere to be seen. If anything, productivity growth has been slower post-1975 than pre-1975 (although other factors have also been at work).

…

REFERENCES

…

Kaldor, N (1980c), Memorandum of Evidence on Monetary Policy submitted to the House of Commons Select Committee on the Treasury and the Civil Service, 17 July, London: HMSO.

…