Yesterday, the Indian government announced a $32 billion plan to recapitalise some banks. These banks have large government ownership. Such issues remain controversial because the government is seen as allowing a lot of bank debtors get away with defaulting on their loans. At any rate, the topic for this post is whether the government plan leads to a rise in deficit or not.

The Chief Economic Advisor clarified on Twitter than according to international standards, it doesn’t lead to a rise in fiscal deficits over the periods during which recapitalisation happens. But people don’t seem to be convinced. So here’s an attempt.

In short, a recapitalisation of banks by the government by an amount of say $100 doesn’t lead to an increase of $100 in deficit. There are some complications, as highlighted below.

It shouldn’t matter but those arguing whether it leads to a rise in deficits are motivated to do so since acceptance by the government will lead to a fall in government expenditures since they are—incorrectly—committed to “fiscal responsibility”.

In the system of national accounts—the latest update of which is the 2008 SNA—there are three main types accounts in the transactions flow account:

- Current accounts

- Capital account

- Financial account

The current accounts record things such as production, generation and distribution of income and so on.

The capital account records transactions in non-financial assets. Para 10.1 of the 2008 SNA describes it:

The capital account is the first of four accounts dealing with changes in the values of assets held by institutional units. It records transactions in non-financial assets. The financial account records transactions in financial assets and liabilities. The other changes in the volume of assets account records changes in the value of both non-financial and financial assets that result from neither transactions nor price changes. The effects of price changes are recorded in the revaluation account. These four accounts enable the change in the net worth of an institutional unit or sector between the beginning and end of the accounting period to be decomposed into its constituent elements by recording all changes in the prices and volumes of assets, whether resulting from transactions or not. The impact of all four accounts is brought together in the balance sheets. The immediately following chapters describe the other accounts just mentioned.

[emphasis: mine]

The financial account is described in para 11.1:

The financial account is the final account in the full sequence of accounts that records transactions between institutional units. Net saving is the balancing item of the use of income accounts, and net saving plus net capital transfers receivable or payable can be used to accumulate non-financial assets. If they are not exhausted in this way, the resulting surplus is called net lending. Alternatively, if net saving and capital transfers are not sufficient to cover the net accumulation of non-financial assets, the resulting deficit is called net borrowing. This surplus or deficit, net lending or net borrowing, is the balancing item that is carried forward from the capital account into the financial account. The financial account does not have a balancing item that is carried forward to another account, as has been the case with all the accounts discussed in previous chapters. It simply explains how net lending or net borrowing is effected by means of changes in holdings of financial assets and liabilities. The sum of these changes is conceptually equal in magnitude, but on the opposite side of the account, to the balancing item of the capital account.

[emphasis: mine]

A recapitalisation of banks is an exchange for equities issued by the bank for funds. The government might raise funds via auctions. The Indian government is even planning to issue something called “recapitalisation bonds” which will be a direct exchange of those bonds with banks for equity. At any rate, these transactions for the government are likely to change the financial account and won’t enter the current accounts and the capital account. So these don’t change the deficit, with the exception below.

It could be the case that the purchase of equity by the government could be not at the market value. So there’s something called capital transfers.

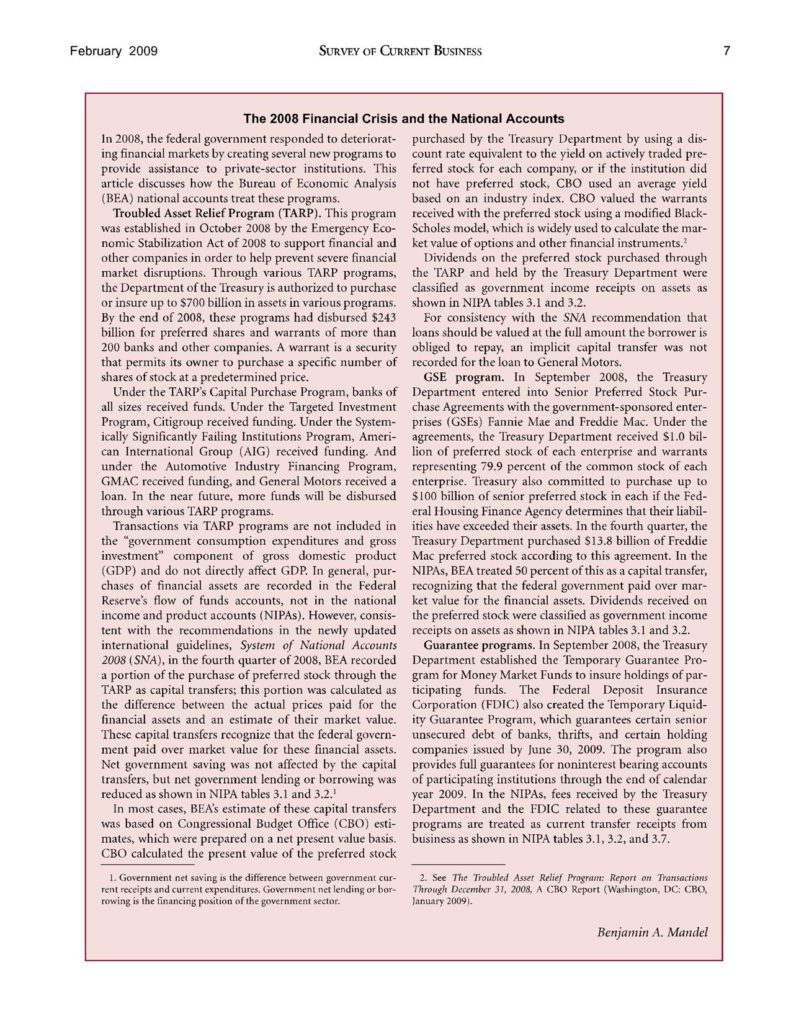

There was a good publication by the BEA which appeared in the Survey of Current Business, February 2009.

click for the pdf file

So the note says:

… consistent with the recommendations in the newly updated international guidelines, System of National Accounts 2008 (SNA), in the fourth quarter of 2008, BEA recorded a portion of the purchase of preferred stock through the TARP as capital transfers; this portion was calculated as the difference between the actual prices paid for the financial assets and an estimate of their market value. These capital transfers recognize that the federal government paid over market value for these financial assets. Net government saving was not affected by the capital transfers, but net government lending or borrowing was reduced as shown in NIPA tables 3.1 and 3.2.

So the full amount of the recapitalisation doesn’t affect the deficit.

In other words, government recapitalisation of banks for an amount $100 doesn’t increase the deficit by $100, but only by the amount mentioned above.

There’s a technicality. If a bank is fully government owned, then it’s the case that the full amount of recapitalisation is the capital transfer. Else it is not.

Also, once a bank is recapitalised, the government pays interest on the bonds and also receives dividends from the ownership. These affect the deficit, and the numbers are also different to the case when a bank isn’t recapitalised or recapitalised by the markets. But for the current purpose, it’s not that important.

It should be simple to understand. If you borrow to buy financial securities for $100, it doesn’t change your deficit or net borrowing (except for brokerage fees and transaction taxes). Your net lending is the difference between your disposable income and expenditure on goods and services. You have borrowed to buy some financial securities but you are also a lender.

Anyway, this simple point was missed even by the US Treasury!