Before I begin, Brian Romanchuk has written a reply to my previous post. Highly likely you have seen it, but if you haven’t check it out. I will reply soon but for now I want to tackle neoclassicals economists’ dubious claims.

The background for readers not having seen recent debates is that Paul Krugman has launched a vicious attack claiming that it is not possible for the U.S. economy to grow at 5.3%. His analysis is just some random averaging of numbers more than anything else. In my argument, it doesn’t matter if it is Bernie Sanders or someone. The question is just about possibilities. The question is: is 5.3% possible in the next four US presidential years?

First, 5.3% over four years is about 23%.

The United States doesn’t have full employment. A lot of people are working part time and many others are discouraged from work. So cannot the U.S. government boost domestic demand and raise real GDP by 23% in four years?

Of course, it can do it.

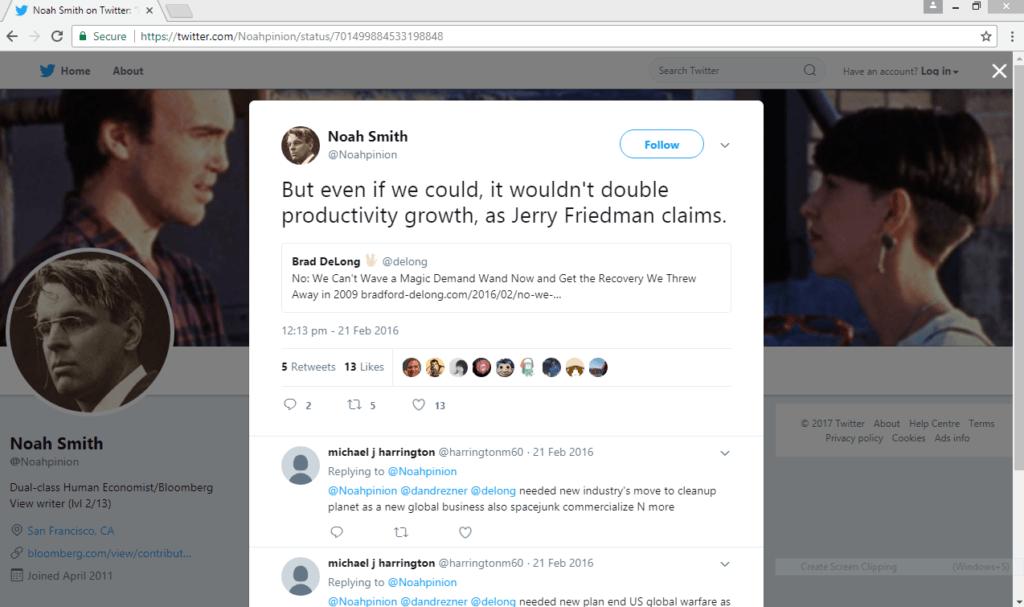

But the debate has been hijacked by debating purely about productivity. Here’s Noah Smith for example:

click to view the tweet on Twitter

So neoclassical economists are making it look as if it is only a matter of rise in productivity.

(Update: Smith has written an article for Bloomberg here)

I am going to argue that productivity is really a sideshow.

Why does productivity matter? If there is full employment and no additions to the labour force, production can only rise if productivity rise. This is purely a matter of definitions and not a causal statement. In fact, the causality is from production to productivity and not the other way round. But if there isn’t full employment, production can rise even if there is no rise in productivity. It’s just about more people who were not employed before, producing more stuff. In addition a lot are also joining the labour force for the first time. So production can rise without productivity rising.

Now with high unemployment and people working part time and people discouraged from looking for work, it is entirely possible that almost the whole of 23% is purely attributed to this.

Think Okun’s Law.

So productivity rises is really a sideshow here. But it’s good if it rises. But it’s sad that the debate is centred around productivity rises.

In summary 23% can be reached by

- Rise in production attributable to no rise in productivity

- Rise in productivity. (Caused by the rise in production itself).

The debate is centred around the point 2. This is not surprising. Neoclassical models are built assuming full employment, so an economist is simply trained to think of point 2 and not think about point 1 at all. As Joan Robinson would say:

Before ever he [a student] does ask, he has become a professor, and so sloppy habits of thought are handed on from one generation to the next.