In the previous post Is Paul Krugman A Verticalist?, I discussed the confusions economists and market commentators have on open market operations. Even top economists such as Krugman suffer from confusions on central banking and monetary matters.

I also mentioned the work of Alfred Eichner on bringing out more clarity on the defensive nature of open market operations. Let’s look at these matters more closely.

Before this let’s look at what people in general think. Most people think of open market operations as some kind of extra activity on the part of the central bank in collaboration with the bureau of engraving and printing and think of it as operational implementation of Milton Friedman’s helicopter drops! So when a central bank such as the Federal Reserve changes its target on interest rates – such as lowering the “Fed Funds target rate”, people start commenting as if the Federal Reserve is undertaking a mystical operation.

This is Monetarist or Verticalist intuition. It is easy to show that open market operations have nothing to do with fiscal policy and as we saw in the previous blog – very little with monetary policy itself. The open market operation of the central bank is not an income/expenditure flow such as government expenditure flows or tax flows and the former does not affect the net worth of the change the net worth of either the domestic private or the foreign sector. Hence it is hardly fiscal. Yet commentators and economists keep arguing that the central bank is “injecting money” into the economy!

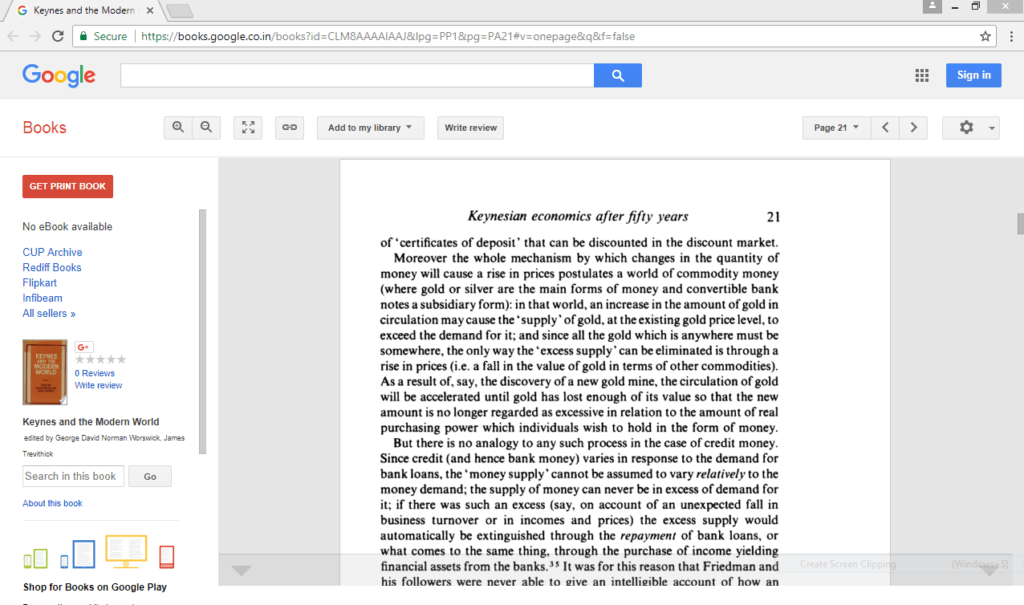

Even Paul Krugman erred on some of these matters and was shown how to do good economics by Scott Fullwiler in his post Krugman’s Flashing Neon Sign. Missing everything Fullwiler was saying, Krugman wrote another post A Teachable Money Moment which has the following diagram:

Below we will see how Krugman’s Neoclassical/New Keynesian (whichever) intuition is flawed.

Setting Interest Rates

These matters (the public understanding) have become worse ever since the Federal Reserve and other central banks around the world started purchasing government debt in the open markets on a large scale – in programs called Large Scale Asset Purchases (also called “QE”). In the following I will consider cases when there is no “asset purchase program” by the central bank and tackle this issue later in another post.

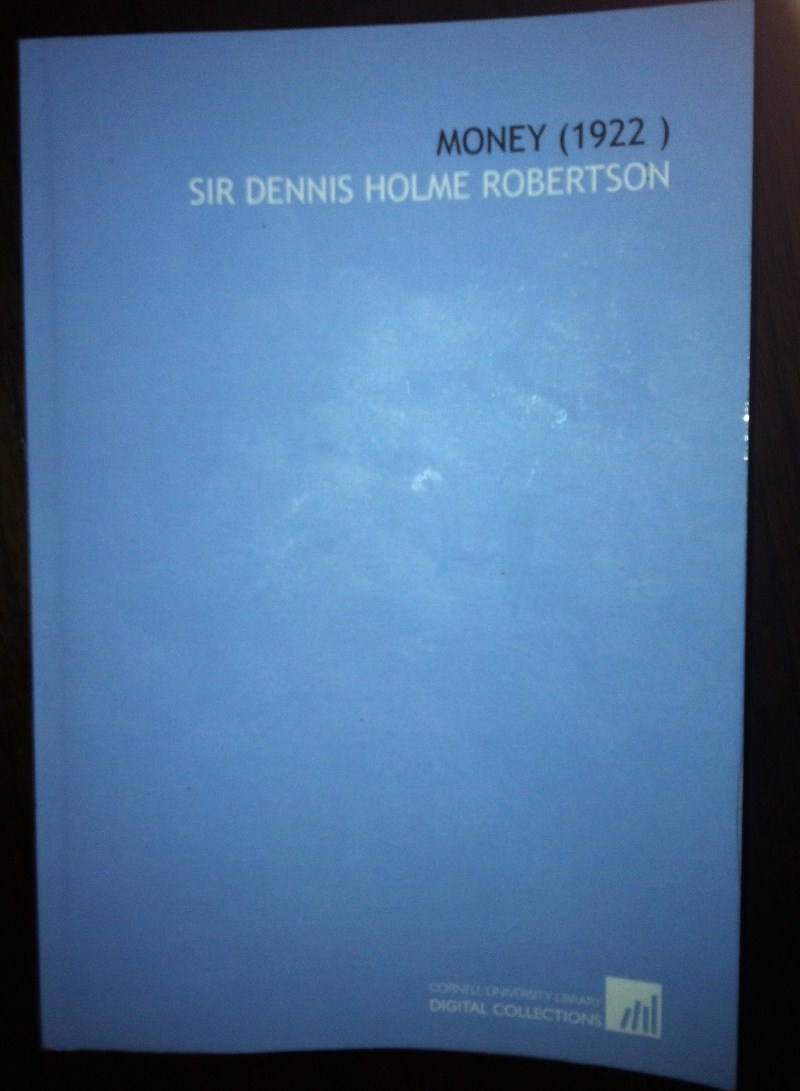

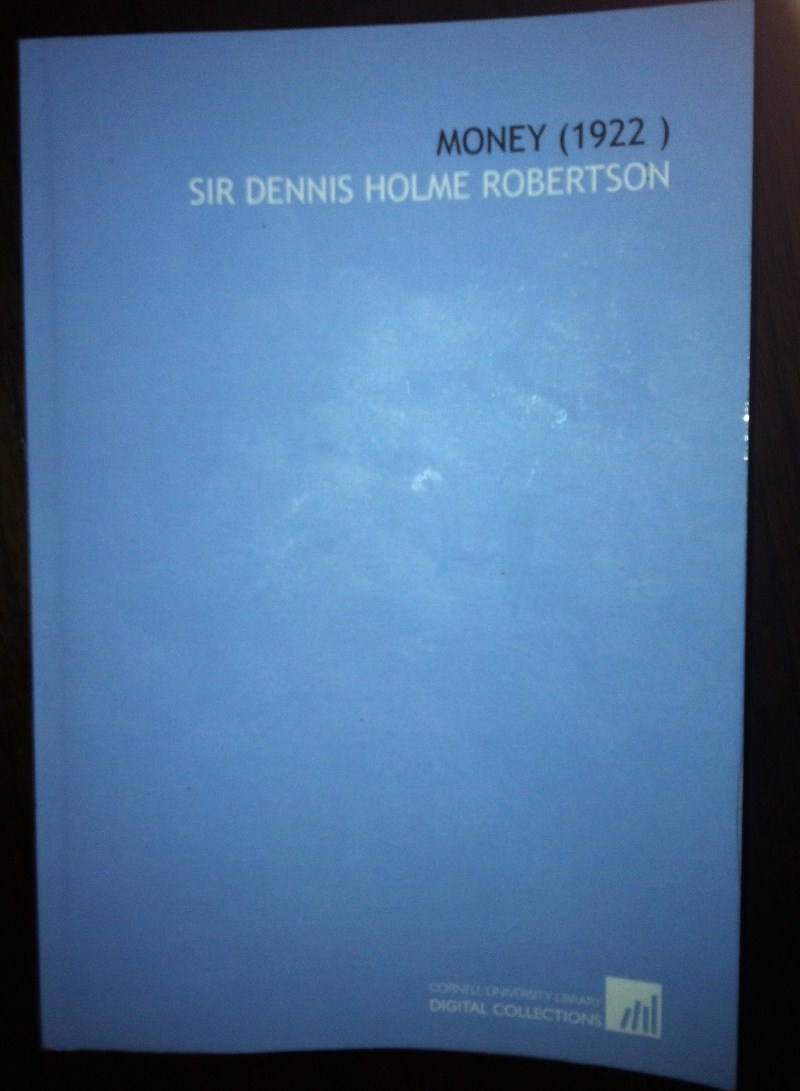

A simple case to highlight how a central bank defends an interest rate (as opposed to changing it) is considering the corridor system. There target for overnight rates is usually at the midpoint of this “corridor”. At the lower end of the corridor banks get paid interest on their settlement balances they keep at the central bank while at the upper end it is the rate at which the central bank lends.

Because banks settle among each other on the books of the central bank, this gives the latter to fix the short-term rates and indirectly influence long term rates.

Why do banks need to settle with each other?

One of the first economists to understand the endogenous nature of money was Sir Dennis Holme Roberston who used to work for the Bank of England. In 1922, he wrote a nice book simply titled Money.

From page 52:

. . . If A who banks at bank X pays a cheque for £10 to B who banks at bank Y, then Bank Y, when it gets the cheque from B, will present it for payment to Bank X: and bank X will meet its obligation by drawing a cheque for £10 on its chequery at the Bank of England. As a matter of fact, the stream of transactions of this nature between big banks is so large and steady in all directions that the banks are enabled to cancel most of them out by an institution called the clearing-house: but the existence of these chequeries at the Bank of England facilitates the payment of any balance which it may not be possible at the moment to deal with in this way …

Because banks finally settle at the central bank finally, central banks have learned since their creation that they can set interest rates. This is strongest at the short end of the “yield curve” but directly or indirectly central banks also influence long term rates.

At the end of each day, some banks will be left with excess of settlement balances (if they see more inflows than outflows) and some banks will face the opposite situation. Because they need to satisfy a reserve requirement at the central bank (which can be zero as well), some banks would need to borrow funds from others. Borrowing means paying back with interest and this is where the central bank’s ability to target rates comes enters the picture.

For suppose some bank X needs funds and other banks wish to lend bank X at a very high interest rate. In this scenario bank X can simply borrow from the central bank, while other banks who demanded higher interest will see themselves with excess settlement balances earning less than the target rate. So it would have been better for the latter to have lent than keep excess balances. (Of course the qualifier is that these things are valid under scenarios when there is less stress on the financial system). Also with the same logic, the rate at which banks lend each other will not fall below the corridor because it will be foolish of a bank to have lent settlement balances to another bank when it could have earned higher by just keeping excess settlement balances at the central bank.

Here is a diagram from the post Corridors And Floors In Monetary Policy from FRBNY’s blog which explains central bank’s operations:

The other system as per this post is the floor system – in which the central bank’s target is the interest paid on settlement balances itself, rather than the midpoint of any corridor. This is what has been followed by the US Federal Reserve in recent times.

Back to the corridor system, an important question arises. Hopefully the reader is convinced that the overnight rate at which banks lend each other is between the corridor. However it is still unclear how and why the central bank can keep it at the midpoint.

If the central bank and the bankers understand the system well, it is possible for the central bank to be quite perfect in this. This happens for example in the case of Canada, where the bank is quite accurate in its objective.

The reason is that the central bank can easily add and subtract settlement balances by various means.

Take an example. Suppose the interest on reserves is 2.25%, the target is 3.00% and the discount rate – the rate at which the central bank lends overnight – 3.75%. If the central bank observes that banks are lending each other at 3.25% – slightly away from the target of 3.00%, it can simply create excess balances. Among the many ways, there are two –

- purchase/sale of government securities and/or repurchase/reverse repurchase agreements.

- shifts of government deposits from the central bank account into the Treasury’s account at banks or the opposite.

So the central bank knows how the curve in the figure above looks like and adds/subtracts settlement balances by the above methods (mainly). So banks are lending each other at 3.25%, the central bank will add settlement balances; if they are lending each other at 2.75% – the central bank will drain settlement balances.

More generally the “threat” by the central bank is reasonably sufficient to make banks lend at the target!

Open Mouth Operations

Let us suppose the central bank had been targeting 3.00% for three months now and decides to decrease rates.

What does it do?

Almost nothing!

The announcement itself will make banks gravitate toward the new target!

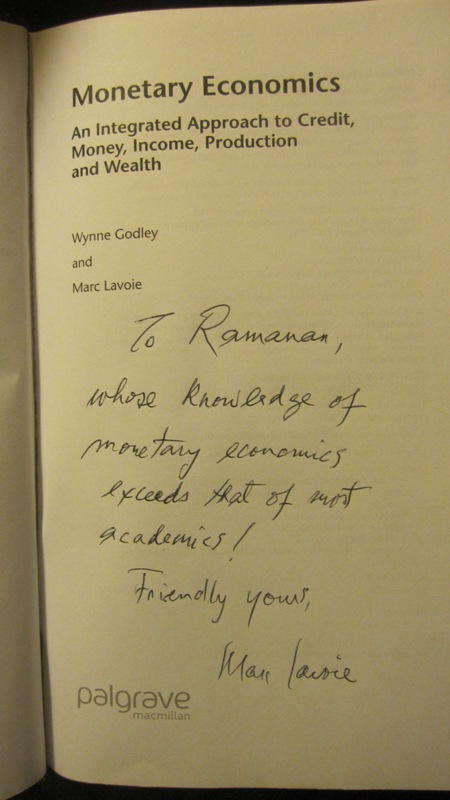

In his paper Monetary Base Endogeneity And The New Features Of The Asset-Based Canadian And American Monetary Systems, Marc Lavoie says:

When they [central banks] are not accommodating—that is, when they are pursuing “dynamic” operations as Victoria Chick (1977, p. 89) calls them—central banks will increase (or decrease) interest rates. As shown above, to do so, they now need to simply announce a new higher target overnight rate. The actual overnight rate will gravitate toward this new anchor within the day of the announcement. No open-market operation and no change whatsoever in the supply of high-powered money are required.

Hence the term “open mouth operations” which was coined by Julian Wright and Greame Guthrie in their paper Market-Implemented Monetary Policy with Open Mouth Operations.

Open Market Operations

The above paper by Marc Lavoie is an excellent source for open market operations and looking at central banking from an endogenous money viewpoint.

I mentioned in the previous post that the open market operations are defensive. In my analysis in this post till now, I ignored the factors which cause settlement balances of the banking sector as a whole to change. Let us bring in this complication.

Apart from banks, the Treasury – the domestic government’s fiscal arm – and other institutions such as foreign central banks, governments and international official institutions (such as the IMF) also keep an account at the (domestic) central bank. When these institutions transact, there is an addition/subtraction of banks’ settlement balances at the central banks.

Here’s one example. Suppose the Treasury transfers funds of $1m to a contractor for settlement of a project done by the latter. When the funds are transferred, the contractor’s bank account increases by $1m and the bank in which he banks sees its deposits and settlement balances rise by $1m while the central bank will reduce the Treasury’s deposits by $1m.

This may lead to a deviation of banks’ lending rate to each other and the central bank needs to drain reserves. The central bank can achieve this by shifting government funds at a bank into the central bank account. If the central bank transfers $1m of funds, banks’ deposits and settlement balances reduce by $1m and the Treasury’s account at the central bank will increase by $1m.

This is not an “open market operation” but another way of adding/draining reserves. In general, depending on institutional setups, the central bank may also do purchase/sale of government securities and/or repurchase agreements.

But this has nothing to do with policy itself – rather it is to maintain status quo. (Of course “large scale asset purchases” is a slightly different matter – first one needs to understand the corridor system).

In other words, this is a defensive behaviour on part of the central bank.

Alfred Eichner

In the previous post and in Alfred Eichner And Federal Reserve Operating Procedures, I mentioned about the contribution of Eichner. In an essay in honour, Alfred Eichner, Post Keynesians, And Money’s Endogeneity – Filling In The Horizontalist Black Box, (from the book Money And Macrodynamics – Alfred Eichner And Post-Keynesian Economics) Louis-Philippe Rochon says:

For Eichner, the overall or “primary objective [of the central bank], in conducting its open market operations, is to ensure the liquidity of the banking system,” which applies to either the accommodating or defensive roles. In either case, Eichner argues that “the Fed’s open market operations are largely an endogenous response to . . . the need both to offset the flows into and out of the domestic monetary-financial system and to provide banks with the reserves they require”; that is, resulting from the demand for money and the demand for credit respectively (1987, 847, 851).

And while the accommodating argument has been debated at length by post-Keynesians, the defensive role has been virtually ignored and only recently rediscovered (see Rochon 1999). Yet it is certainly Eichner’s greatest contribution to the post-Keynesian theory of endogenous money. . .

. . . The “defensive” behavior is defined by Eichner as the “component of the Fed’s open market operations [consisting] of buying or selling government securities so that, on net balance, it offsets these flows into or out of the monetary-financial system,” leaving the overall amount of reserves unchanged. This is the result of changes in portfolio decisions and increases or decreases in bank (demand) deposits. As a result of an increase in the nonbank’s desire to hold currency, for instance, “in order to maintain bank reserves at the same level, the Fed will need to purchase in the open market government securities equal in value to whatever additional currency the nonbank public has decided to hold” (Eichner 1987, 847).

In making the distinction between temporary and permanent open market operations, Rochon also quotes Scott Fullwiler:

Outright or permanent open market operations are primarily undertaken to offset the drain to Fed balances due to currency withdrawals by bank depositors. . . . Temporary open market operations are aimed at keeping the federal funds rate at its target on average through temporary additions to or subtractions from the quantity of Fed balances. Temporary operations attempt to offset changes in Fed balances due to daily or otherwise temporary fluctuations in the Treasury’s account, float, currency, and other parts of the Fed’s balance sheet, in as much as is necessary to meet bank’s demand for Fed balances. (2003, 857)

Paul Krugman

All this is completely opposite of Paul Krugman’s position that

. . . And currency is in limited supply — with the limit set by Fed decisions.

And Krugman’s mistake is not minor – it seems he is completely unaware of the huge difference money endogeneity makes.

So what is the difference between Krugman’s diagram and the one from FRBNY blog – even though they look similar? The difference is that the latter is descriptive of behaviour when policy is unchanged and is useful for describing open market operations etc while Krugman uses the same to describe policy changes – which in reality happen via open mouth operations. Paul Krugman confuses open market operations and open mouth operations. So much for a “teachable money moment”.

Krugman also shows his Monetarist intuition by claiming:

And which point on that curve it chooses has large implications for the economy as a whole. In particular, the Fed can always choke off a private-sector credit boom by moving up and to the left.

implying that the central bank in reality controls the monetary base and thence the money stock.

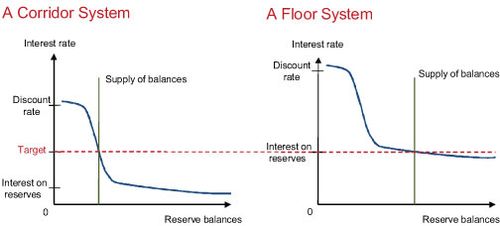

Some Post Keynesians argued since long ago that the central bank cannot control the money stock:

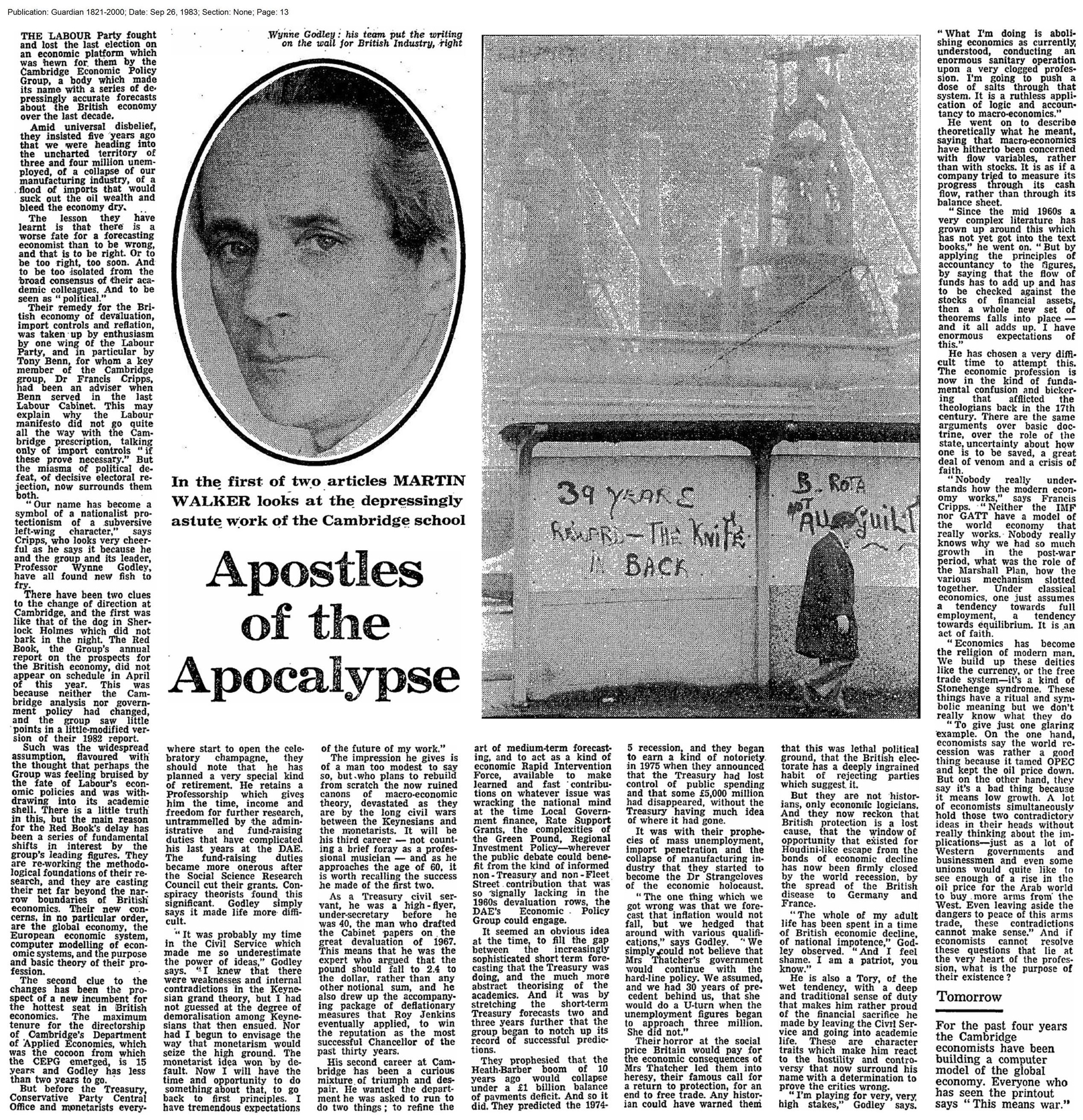

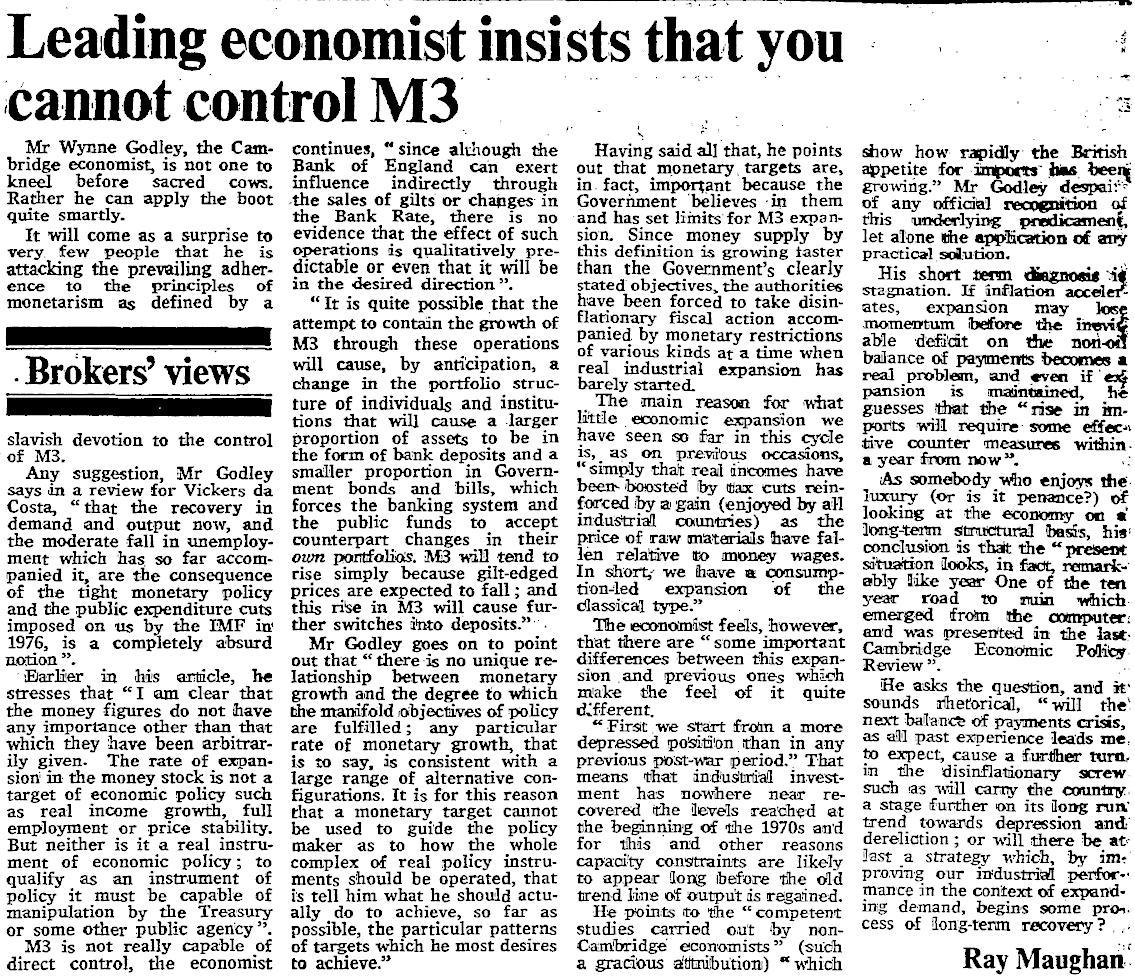

Here’s on Wynne Godley from from The Times, 16 June 1978:

(click to enlarge)