In an article (obituary), Nicholas Kaldor, 12 May 1908-30 September 1986, Geoff Harcourt said:

Nicholas Kaldor’ resembled Keynes more than any other twentieth-century economist because of the breadth of his interests, his wide-ranging contributions to theory, his insistence that theory must serve policy, his periods as an adviser to governments, his fellowship at King’s and, of course, his membership of the House of Lords.

I was reading this article (for the 3rd time!) Kaldor And The Kaldorians by John E. King. It appears as a chapter in the book Handbook Of Alternative Theories Of Economic Growth edited by Mark Setterfield.

I came across this strong Kaldorian view (which I share):

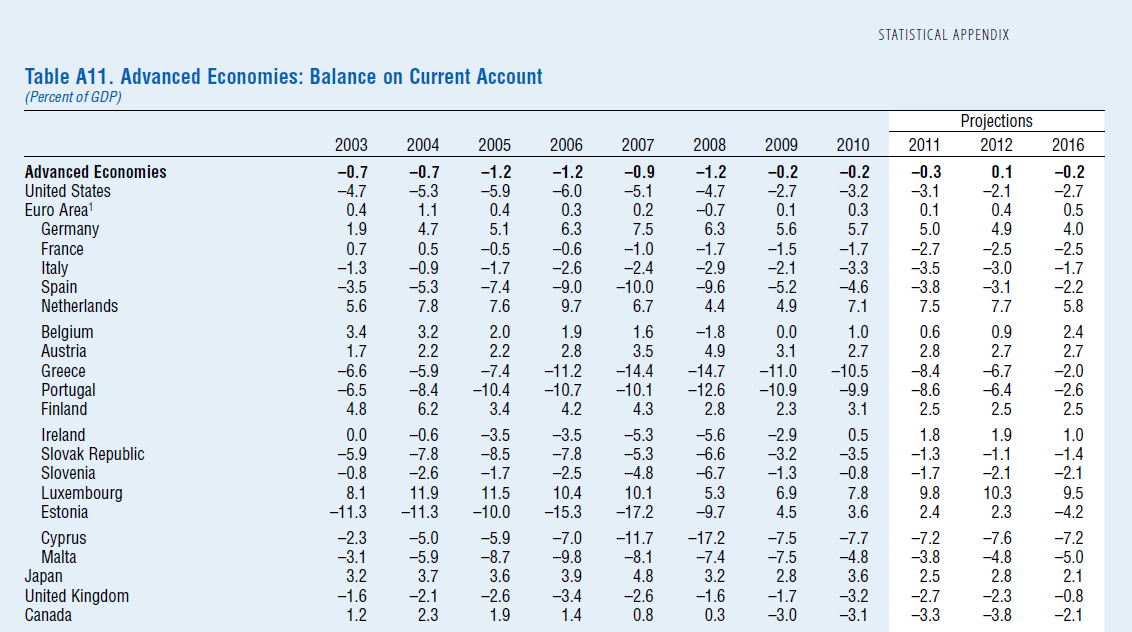

How, exactly, does the constraint [balance-of-payments constraint] operate? Three mechanisms can be distinguished. First, in extreme cases like Cuba in the 1990s and Zimbabwe in the 2000s, a shortage of foreign exchange makes it impossible fully to operate the existing capital stock (since spare parts can no longer be imported), and growth declines or becomes negative. Second, during the fixed exchange rate regime imposed by the Bretton Woods system (1945–73), governments were forced to implement deflationary monetary and fiscal policies to protect the currency in face of often quite small payments deficits. This generated the “stop–go” cycle that Kaldor regarded as the principal cause of Britain’s poor growth performance in this period. Third, in a floating exchange rate regime, the principal constraint on output growth is the rate of growth of export demand. Kaldor himself came to believe that exports were the only source of autonomous aggregate demand, since all other categories of expenditure were fully determined by income: consumption directly, investment indirectly through the accelerator coefficient, and government spending indirectly through taxation receipts, themselves a function of income. This is a characteristically extreme position, which is difficult to justify. But it is not necessary to deny the existence of some autonomous consumption, investment and government spending in order to recognise the importance of export demand as a factor in economic growth. For most small countries, and for all regions within countries, exports are indeed the most important factor.

I am not sure if King’s description of Kaldor and the Kaldorians is the best but a decent one. So, as King hints, Kaldor fully understood the injection to demand due to government expenditure and private sector borrowing. In fact, one whose views closely resembled that of Kaldor was Wynne Godley.

How are exports determined?

Nicholas Kaldor, Geneva, 1948

Picture source: Economica

Kaldor had the following to say:

The growth of a country’s exports should itself be considered as the outcome of the efforts of its producers to seek out potential markets and to adapt their product structure accordingly. Basically in a growing world economy the growth of exports is mainly to be explained by the income elasticity of foreign countries for a country’s products; but it is a matter of the innovative ability and adaptative capacity of its manufacturers whether this income elasticity will tend to be relatively large or small.

in “The role of Increasing Returns, Technical Progress and Cumulative Causation in the Theory of International Trade and Economic Growth”, Economie Appliquée, 1981

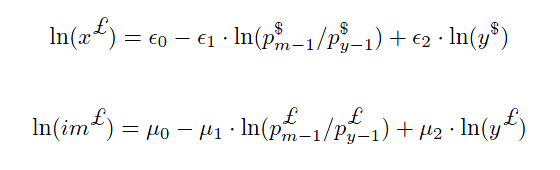

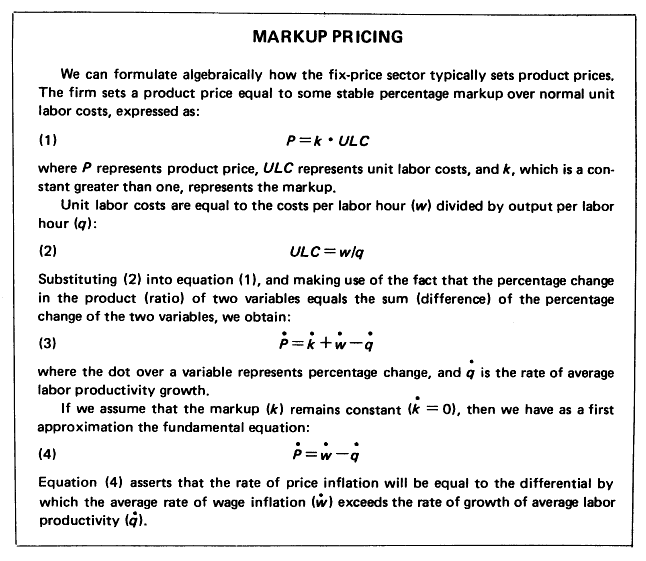

This is oft-quoted by economists who are inspired by Kaldor’s work. This may look straightforward but in my opinion, it is not so in practice. There are just too many different kinds of stories one hears about the external sector from economists. In stock-flow-consistent Post Keynesian macro modelling literature, one sees equations such as

The algebra is involved and there are many more equations than the above two. To get exports and imports, one has to multiply the x£ and im£ by prices. Refer Godley&Lavoie’s text Monetary Economics, oft referred in this blog.

The above equation assumes important causalities. Exports of a nation depends on prices of exported products relative to domestic prices of products in the foreign country, for example. In addition, exports also depend on demand and income in the foreign country(y$). The parameter ε2 (and μ2 from foreigners’ viewpoint) is what Kaldor is talking of in the quote above. The more competitive producers in the £-country are, the higher ε2 will be. Of course, this is not the only important thing, and prices are also important. (For example, if the GBP starts appreciating, UK exporters will face pressures in selling their products in the US).

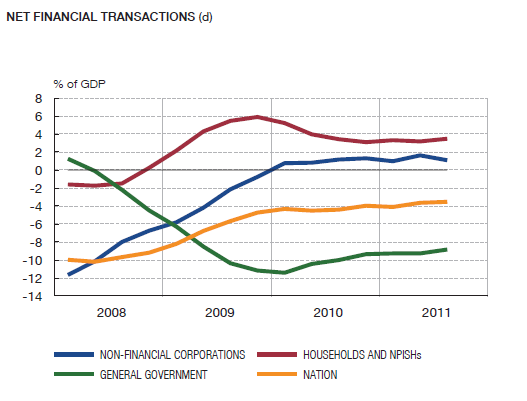

The above equation also shows that if there are injections to demand, such as from government expenditure or tax cuts or due to higher private expenditure (either by higher borrowing or an increased propensity to consume etc), imports will increase. Similarly, if there is a contraction, imports will decrease as was evident by the collapse of world trade due to recessions in many parts of the world during the “Great Recession”.

The purpose of my post was to highlight what importance economists give to price-elasticity and income-elasticity of exports/imports. Most economists worry too much about ε1 (and μ1) and Kaldorians pay much more attention to ε2 (and μ2) and what sorts of policies governments should follow based on this. For example, a nation’s government may be concentrating too much in promoting exports of goods and services where price-competitiveness plays a role. It may be beneficial if it switches to promoting exporting goods and services in which it has unique capabilities which if successful will greatly improve its external situation.

In fact, according to the work of Kaldorians such as Anthony Thirwall and John McCombie, growths of nations can be explained by the ratio of the rate of growth of exports to the income elasticity of its imports. In the stronger form, exports themselves depend on the income-elasticity of imports in the foreign nation – i.e., the “non-price competitiveness” of exporters.

The two authors wrote an excellent book in 1994: Economic Growth And The Balance-Of-Payments Constraint – considered one of the greatest books in Post-Keynesian Economics.