This is the fifth part of the series of posts on the description of the Eurosystem. In this post, I will discuss whatever I had kept postponing in previous posts – except central bank swaps, which I will postpone to Part 6.

[Links for previous parts: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4]

The Euro Area is comprised of 17 nations using the Euro as the legal tender and this is referred to as EA17. In addition, 10 more nations potentially can join the Euro, so they refer to “EU27”. In the recent “summit to end all summits”, European leaders believed in Merkels and worked toward changing the Treaty. UK’s Prime Minister David Cameron refused to sign the new European accord – a wonderful thing to do.

[The UK always had an opt-out option and this move effectively divorces the UK from EU. The other nation with an opt-out is Denmark. The remaining 8 are: Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania and Sweden. The Wikipedia entry Enlargement of the Euro Zone has good details.]

Before the summit of political leaders, the ECB, in its monthly monetary policy meeting, decided to take steps to improve banks’ conditions: It will now conduct two LTROs with a maturity of 36 months and reduced reserve requirements from 2% to 1%. Other than that, it allowed NCBs to accept bank loans satisfying certain criteria as collateral and reduced the ratings threshold on Asset-Backed Securities. Before this, the maximum maturity of LTRO till date was 1 year.

In the press conference that followed, Mario Draghi, the President of the ECB, dashed market hopes of a more aggressive intervention of the ECB in the markets. The press conference transcript is here. However, analysts saw this as a signal from the ECB to force Euro Area governments into agreeing into fiscal contraction ahead of the summit and still expect the ECB to intervene.

Securities Markets Programme

Back in May 2010, the ECB observed that yields of a few “peripheral” government bonds were rising and it looked as if it could become a “self-fulfilling prophecy” and decided to intervene in the markets. In the ECB’s words, the Governing Council decided to:

To conduct interventions in the euro area public and private debt securities markets (Securities Markets Programme) to ensure depth and liquidity in those market segments which are dysfunctional. The objective of this programme is to address the malfunctioning of securities markets and restore an appropriate monetary policy transmission mechanism. The scope of the interventions will be determined by the Governing Council. In making this decision we have taken note of the statement of the euro area governments that they “will take all measures needed to meet [their] fiscal targets this year and the years ahead in line with excessive deficit procedures” and of the precise additional commitments taken by some euro area governments to accelerate fiscal consolidation and ensure the sustainability of their public finances.

In order to sterilise the impact of the above interventions, specific operations will be conducted to re-absorb the liquidity injected through the Securities Markets Programme. This will ensure that the monetary policy stance will not be affected.

The outstanding amount held (settled, to be precise) by the Eurosystem as on Dec 2 was about €207bn, as per this link.

This has continued to rise in recent months because of rising yields of government bonds with markets suspecting that the public debts of Spain and Italy are on unsustainable territory. So the Eurosystem intervenes frequently and the market participants quickly figure this out.

Who Buys – NCBs or ECB?

Some people have asked me – who buys the bonds: NCBs or the ECB? The answer – I believe – is both. Someone asked me if there are traders in the ECB building at Frankfurt. I do not know – perhaps a few. Someone pointed out that the ECB may be buying using the NCB as its agent. Possible. There’s another question, which nobody has asked me – does an NCB of country A buy government bonds of country B? I think so. Who decides all this is not an easy question!

For example, according to the Banque de France Annual Report 2010, (page 118 of publication, 108 of pdf)

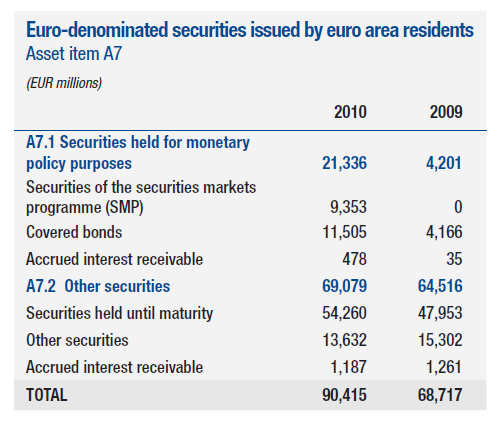

The total amount of securities held by NCBs of the Eurosystem under the SMP increased to EUR 60,873 million, of which EUR 9,353 million are held by the Banque de France and are shown under asset item A7.1 in its balance sheet. Pursuant to Article 32.4 of the ESCB statute, any risks from the holding of securities under the Securities Markets Programme, if they were to materialise, should eventually be shared in full by the NCBs of the Eurosystem in proportion to the prevailing ECB capital key shares.

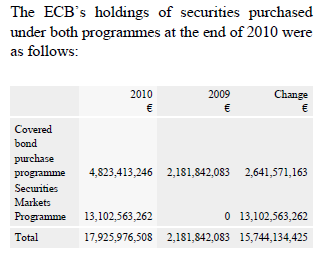

What about the ECB? Yes. According to the ECB Annual Report 2010, page 223 (page 224 of pdf):

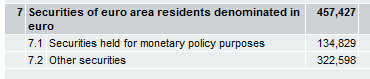

Compare that to the Eurosystem’s consolidated balance sheet item (7.1 below) which was large compared to €17.9bn above at the end of 2010:

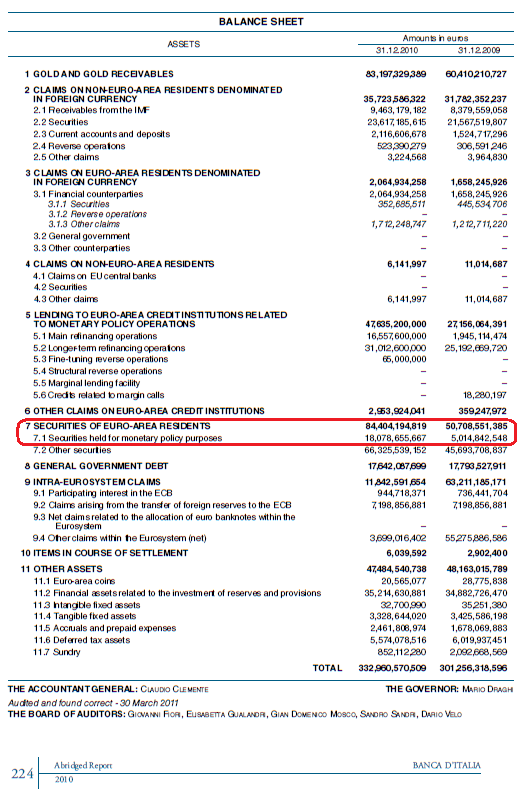

Also, according to Banca d’Italia’s Annual Report 2010 (page 224 of publication, 231 of pdf):

“Securities held for monetary policy purposes” was about €18bn at the end of 2010, of which about €8bn was in government bonds under SMP and the remaining covered bonds.

So to summarize, government debt is purchased by all NCBs and the ECB and the NCB purchase is not restricted to purchasing government bonds of the same nation the NCBs are located.

The same is true with the Covered Bonds Purchase Programme. The latter is somewhat equivalent to the Federal Reserve’s purchase of Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities in the United States. Covered Bonds are somewhat similar to Asset-Backed Securities such as MBS; the former are on balance sheet of the issuing bank, unlike the latter which are moved into Special Purpose Entities. The assets backing covered bonds are clearly identified in a “cover pool” and are “ring-fenced” which means that if the issuing bank closes down due to insolvency, the assets in the covered pool will be used to pay the covered bond holders, before they are available to unsecured creditors including depositors. The reason the ECB has chosen covered bonds instead of ABS is because of the strength of the covered bond lobby in Europe.

Emergency Loan Assistance

Imagine the following. A Euro Area country X’s government bond yields are at rising and the bond markets are highly suspicious of the government’s solvency. Banks are also in a bad situation and funds have made frequent flights out of the country. The banks have provided all collateral they had to their home NCB. (To be technically correct, foreign assets are pledged to the respective foreign NCB who acts as a custodian for the home NCB). The government has €8bn of payments to bond holders this week. The government has enough funds deposited at a local bank, so it can meet its obligations. However, most bond holders are foreigners. When the government pays the bond holders, the payment will go through via TARGET2 and commercial banks will run out of collateral to provide to their home NCB.

The above is one way in which banks can run out of collateral and there are other ways in which the government is not the direct reason for the outflow of funds, such as a simple capital flight. For this reason, some NCBs invented a programme called “Emergency Loan Assistance” which may not have been a terminology used in the Treaty. The relevant article which may provide an NCB with this power is the Article 14.4 of the Statute of the ESCB and of the ECB

14.4. National central banks may perform functions other than those specified in this Statute unless the Governing Council finds, by a majority of two thirds of the votes cast, that these interfere with the objectives and tasks of the ESCB. Such functions shall be performed on the responsibility and liability of national central banks and shall not be regarded as being part of the functions of the ESCB.

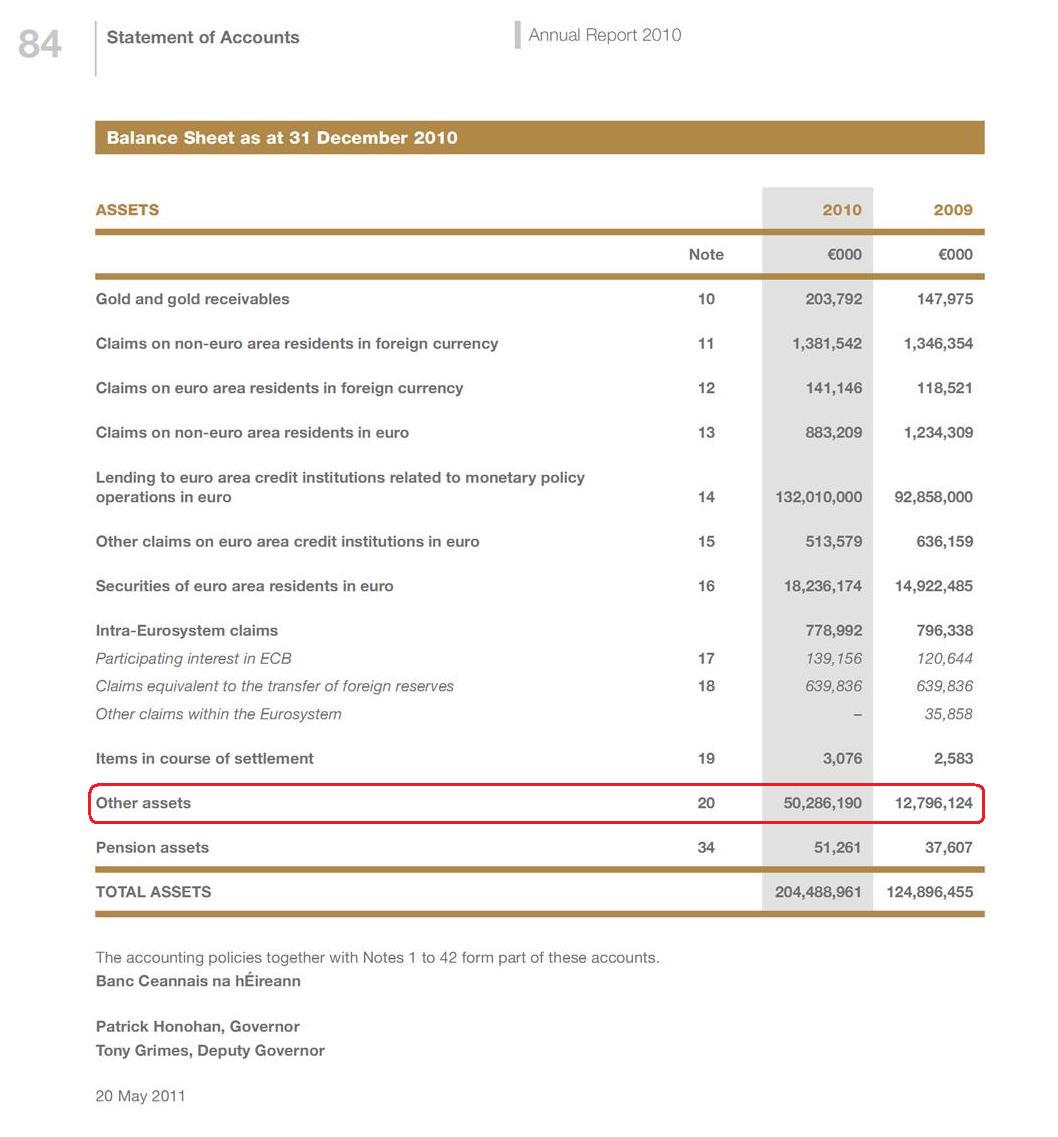

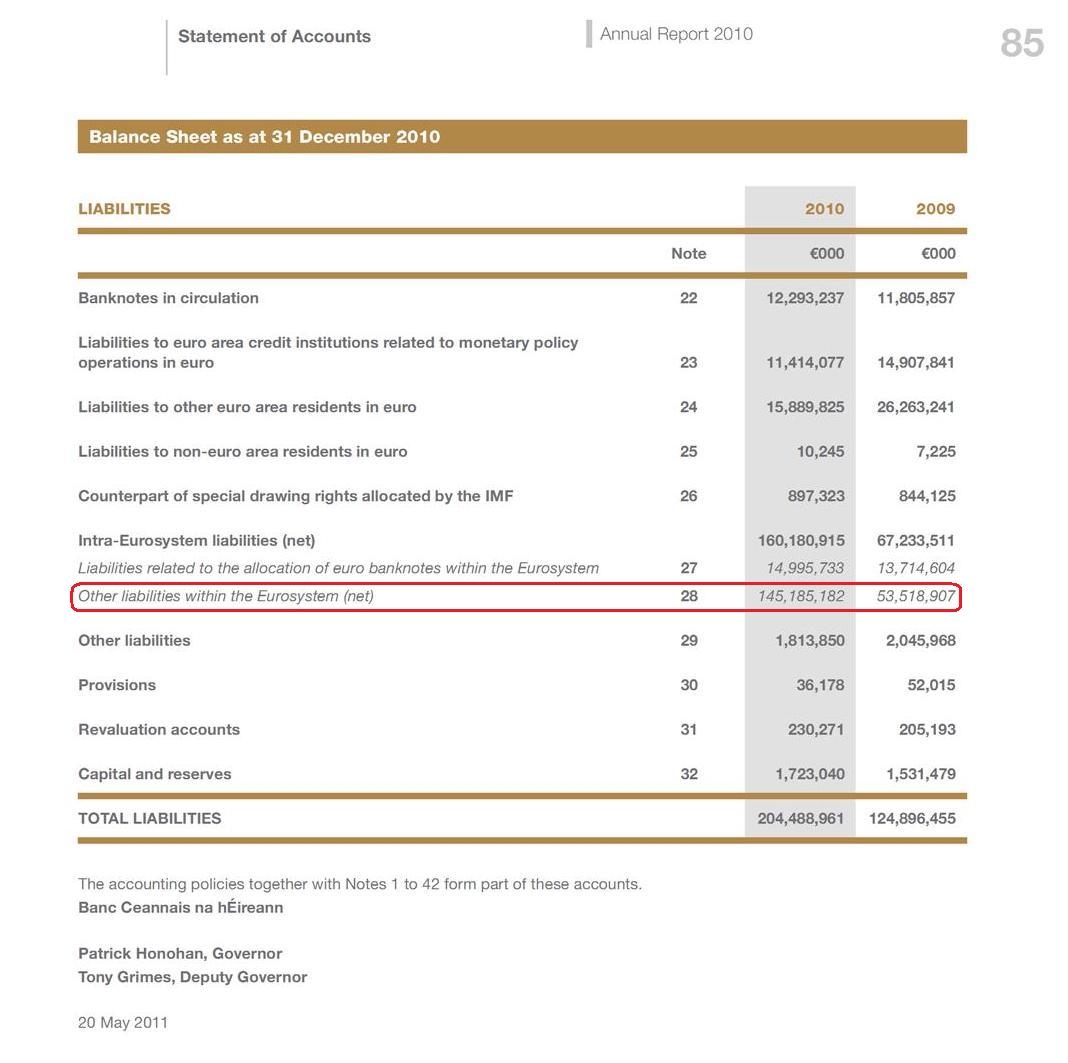

The situation highlighted above happened frequently with Greece during the past few months. The ELA, however was first used by Ireland in 2010. From the Central Bank of Ireland Annual Report 2010

The item highlighted “Other Assets” contains the balance sheet item for Emergency Loan Assistance. More below, but before this, it is instructive to look at Liabilities:

So, the Central Bank of Ireland’s Liabilities to the rest of the Eurosystem was around €145bn! – which is indicative of how much funds flew out of Ireland and the amount of stress the nation went through. (Ireland’s 2010 GDP was €154bn, btw). I described how funds flow within the Euro Area in Part 2 of this series.

Back to ELA. Page 104 of the publication (106 of the pdf) describes Other in Other Assets as:

This includes an amount of €49.5 billion (2009: €11.5 billion) in relation to ELA advanced outside of the Eurosystem’s monetary policy operations to domestic credit institutions covered by guarantee (Note 1(v)). These facilities are carried on the Balance Sheet at amortised cost using the effective interest rate method. All facilities are fully collateralised and include sovereign collateral as well as a broad range of security pledged by the counterparties involved.

The Bank has in place specific legal instruments in respect of each type of collateral accepted. These comprise: (i) Promissory Notes issued by the Minister for Finance to specific credit institutions and transferrable by deed, (ii) Master Loan Repurchase Deeds covering investment/development loans, (iii) Framework Agreements in respect of Mortgage-Backed Promissory Notes covering non-securitised pools of residential mortgages, (iv) Special Master Repurchase Agreements covering collateral no longer eligible for ECB-related operations and (v) Facility Deeds providing a Government Guarantee. In addition, the Bank received formal comfort from the Minister for Finance such that any shortfall on the liquidation of collateral is made good. Where appropriate, haircuts (ranging from 5.5 per cent to 80 per cent) have been applied to the collateral. Credit risk is mitigated by the level of the haircuts and the Government Guarantee. At the Balance Sheet date no provision for impairment was recognised.

You can find details of these in this blog post Irish Central Bank Comfort at the blog called Corner Turned, which is now inactive.

Oh yeah … How does the Irish NCB provide the loans? Hint: Loans make deposits.

FT Alphaville has two nice posts (among others) on ELA in Greece: Sundry secret Greek liquidity [updated], Hooray for, erm, Greek ELA?. The first one pokes on how the Bank of Greece – Greece’s NCB – hides the item under “Sundry” and the second one one how Greek banks’ net interest income were higher than expected – the reason being that expensive deposits were replaced by cheaper NCB funding!

This concludes this post. In Part 6 – the final one – I will discuss central bank liquidity swap lines with the Federal Reserve.