A lot has been written on helicopter money recently. Most of them bad with a few exceptions such as one by JKH.

In my opinion, the main reason economists come up with stories such as “helicopter money” etc. is that it is difficult in standard economic theory to introduce money.

Few quotes from Mervyn King’s book The End of Alchemy: Money, Banking, and the Future of the Global Economy:

But my experience at the Bank also revealed the inadequacies of the ‘models’ – whether verbal descriptions or mathematical equations – used by economists to explain swings in total spending and production. In particular such models say nothing about the importance of money and banks and the panoply of financial markets that feature prominently in newspapers and on our television screens. Is there a fundamental weakness in the intellectual economic framework underpinning contemporary thinking? [p 7]

For over two centuries, economists have struggled to provide a rigorous theoretical basis for the role of money, and have largely failed. It is a striking fact that as as economics has become more and more sophisticated, it has had less and less to say about money… As the emininent Cambridge economist, and late Professor Frank Hahn, wrote: ‘the most serious challenge that the existence of money poses to the theorist is this: the best developed model of the economy cannot find room for it’.

Why is modern economics unable to explain why money exists? It is the result of a particular view of competitive markets. Adam Smith’s ‘invisible hand’ …

… Money has no place in an economy with the grand auction. [pp 78-80]

But the ex-Bank of England governor perhaps never worked with stock flow consistent models. The advantage of these models is that what money is and how it is created is central to the question of how economies work. The framework used in stock flow consistent models is not new exactly. What’s new in stock-flow consistent models is the behavioural analysis on top of the existing framework the system of national accounts and flow of funds. As Morris Copeland, who formulated the flow of funds accounts of the U.S. economy said:

The subject of money, credit and moneyflows is a highly technical one, but it is also one that has a wide popular appeal. For centuries it has attracted quacks as well as serious students, and there has too often been difficulty in distinguishing a widely held popular belief from a completely formulated and tested scientific hypothesis.

I have said that the subject of money and moneyflows lends itself to a social accounting approach. Let me go one step farther. I am convinced that only with such an approach will economists be able to rid this subject of the quackery and misconceptions that have hitherto been prevalent in it.

– Morris Copeland, Social Accounting For Moneyflows in Flow-of-Funds Analysis: A Handbook for Practitioners (1996) [article originally published in 1949]

So what do we mean by helicopter money and it is really needed or useful? For that we need to go into a bit into some behavioural equations in stock-flow consistent models. One way is to use a somewhat simplified notation from Tobin’s nobel prize lecture Money and Finance in the Macroeconomic Process. In Tobin’s analysis, the government’s fiscal deficit is financed by high-powered money and government bonds:

G – T = ΔH + ΔB

ΔH = γH·(G – T)

ΔB = γB·(G – T)

γH + γB = 1

0 ≤ γH, γB ≤ 1

So the deficit is financed by “high-powered money” (H) and government bonds (B) in proportion γH and γB

Now it is important to go into a bit of technicalities. Prior to 2008, central banks implemented monetary policy by a corridor system. After 2008, when the financial system needed to be rescued and later when central banks started the large scale asset purchase program (“QE”), central banks shifted to a floor system.

Although economics textbooks keep claiming that the central bank “controls the money supply”, in reality they are just setting interest rates.

In the corridor system, there are three important rates:

- The deposit rate: The rate at which central banks pay interest on banks’ deposits (reserves) with them,

- The target rate: The rate which the central bank is targeting, and is typically the rate at which banks borrow from each other, overnight, at the end of the day.

- The lending rate: The rate at which the central bank will lend to banks overnight.

There are many complications but the above is for simplicity. Typically the target rate is mid-way between the lower (deposit rate) and the higher (lending rate).

In the floor system, the government and the central bank cannot set the overnight at the target rate if the central bank doesn’t supply as much reserves as demanded by banks. Else the interest rate will fall to the deposit rate or rise to the lending rate. In a system with a “reserve-requirement”, banks will need an amount of reserves deposited at the central bank equal to a fraction of deposits of non-banks at banks.

So,

H = ρ·M

where M is deposits of non-banks at banks and ρ is the reserve requirement. In stock-flow consistent models, M is endogenous and cannot be set by the central bank. Hence H is also endogenous.

In the floor system, the target rate is the rate at which the central bank pays interest on deposits. Hence the name “floor”. There are some additional complications for the Eurosystem, but let’s not go into that and work in this simplification.

In the floor system, the central bank and the government can decide the proportions in which deficit is financed between high powered money and government bonds. However since deposits are endogenous the relation between high powered money and deposits no longer holds.

In short,

In a corridor system, γH and γB are endogenous, M is endogenous and H = ρ·M. In a floor system, γH and γB can be made exogenous, M is endogenous and H ≠ ρ·M. M is not controlled by the central bank or the government in either cases and is determined by asset allocation decisions of the non-bank sector.

Of course, the government deficit G – T itself is endogenous and we should treat the government expenditure G and the tax-rates θ as exogenous not the deficit itself.

So we can give some meaning to “helicopter money”. It’s when the central bank is implementing monetary policy by a floor system and γH and γB are exogenous.

But this doesn’t end there. there are people such as Ben Bernanke who have even proposed that the central bank credit government’s account with some amount and let it spend. So this introduces a new variable and let’s call it Gcb.

So we have a corridor system with variables G and θ versus a floor system with variables G’, G’cb, θ, γ’H and γ’B

The question then is how is the latter more superior. Surely the output or GDP of an economy is different in the two cases. However people constantly arguing the case for “helicopter money” are in the illusion that the latter case is somewhat superior. Why for example isn’t the vanilla case of a corridor system with higher government expenditure worse than “helicopter money”.

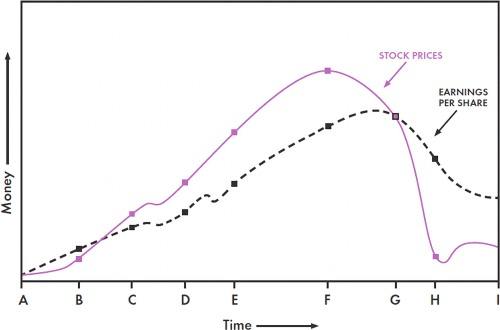

Also it effectively reduces to a fiscal expansion combined with a large scale asset purchase program of the central bank (“QE”). I described QE’s effect here. Roughly it works by a wealth effect on output with some effect on investment via asset allocation.

To summarize, the effect on output by these crazy ways can be achieved by a higher fiscal expansion. There’s hardly a need to bring in helicopters. Some defenders say that it is faster but that just sounds like an excuse to not educate policymakers.