This is the first part of a series of posts I intend to write on the “rest of the world” accounts in National Accounts. This blog is about looking at economies from the point of view of National Accounts, Cambridge Keynesianism and Horizontalism. While various descriptions of balance of payments exist, most of them simply end up making money exogeneity assumption somewhere in the description!

In my view a careful description of balance of payments offers great insights on how economies work and what money really is. It is impossible to understand the success and failures of nations without understanding the external sector.

A description in terms of stocks and flows is the most appropriate for macroeconomics. Fortunately, national accountants have a good systematic approach to this.

Consider the following transaction: a government (or a corporation) raises funds in the international markets. The buyers can be residents as well as non-residents. The currency of the new issuance can be domestic as well as foreign. Does this by itself increase the net indebtedness of the nation as a whole?

The answer is No, and can be a bit surprising to the reader because the answer is the same whether the currency is domestic or foreign. The trick in the question is that an issuance of debt increases the assets and liabilities of the issuer!

(Note: the question was about the transaction, not on what happens after this)

Gross assets and liabilities vis-à-vis the rest of the world can be a bit more complicated and we need a more systematic analysis.

Consider another transaction. A government is redeeming a 7% bond with a notional of 1bn with semi-annual coupons. How much does the net indebtedness of the country change? Assuming that all the lenders are in the rest of the world sector, the net indebtedness changes by 35m. Does not matter if the currency is domestic or not. Why 35m? Because the semi-annual coupon has to be paid on redemption and the coupons are interest payments and this is recorded in the current account and this increases the net indebtedness. The principal payment cancels out the earlier liability – the bonds.

So between the start and the end of the period, foreigners earned 35m and this increased the net indebtedness of the nation who paid the interest. Of course there are other transactions which can cancel this out.

In another scenario, if all the bond holders were residents, the net indebtedness does not change – whether the bonds were in domestic currency or not.

The above was about financing. What about imports and exports? Exports provide income to a nation or a region as a whole and imports are opposite. If a nation is a net importer (more appropriately running a current account deficit), this means its expenditure is higher than income. When expenditure is higher than income, this has to be financed and this is via net borrowing.

There is one important point worth stressing. Many people – including many economists (most?) – treat liabilities to foreigners in domestic currency as not really a liability at all – at least the government’s liabilities. The reason provided is that while usually the government is forbidden from making an overdraft at the central bank or have limited powers in using central bank credit, it can end up making a higher use of it than the limits allowed – in extreme conditions. This in my opinion, is a silly intuition.

While it is true that the governments of most nations (with exceptions such as the Euro Area governments) can make a draft at the central bank and this offers the government protection to tide over extreme emergencies, the government has to directly or indirectly finance the current account deficits and this can prove unsustainable. Despite this there is an advantage in having indebtedness to foreigners in the domestic currency because:

An indebtedness to foreigners in domestic currency prevents revaluation losses on the debt if foreigners continue holding the debt and if the currency depreciates against foreign currencies. If the debt is denominated in a foreign currency and if it depreciates, more income needs to be earned from abroad to service the principal and interest payments.

The discussion can be confusing because of the relative ease with which the United States has managed till now to finance its current account deficits because the US dollar is the reserve currency of the world and continues to do so and the holders are willing to accept liabilities of resident sectors of the United States, especially the government’s at low interest rates/yields.

James Tobin, who has provided the best description of the meaning of government deficits and debt said this in an article “Agenda For International Coordination Of Macroeconomic Policies” (Google Books link)

Nonzero current accounts must be financed by equivalent capital movements, in part induced by appropriate structure of interest rates.

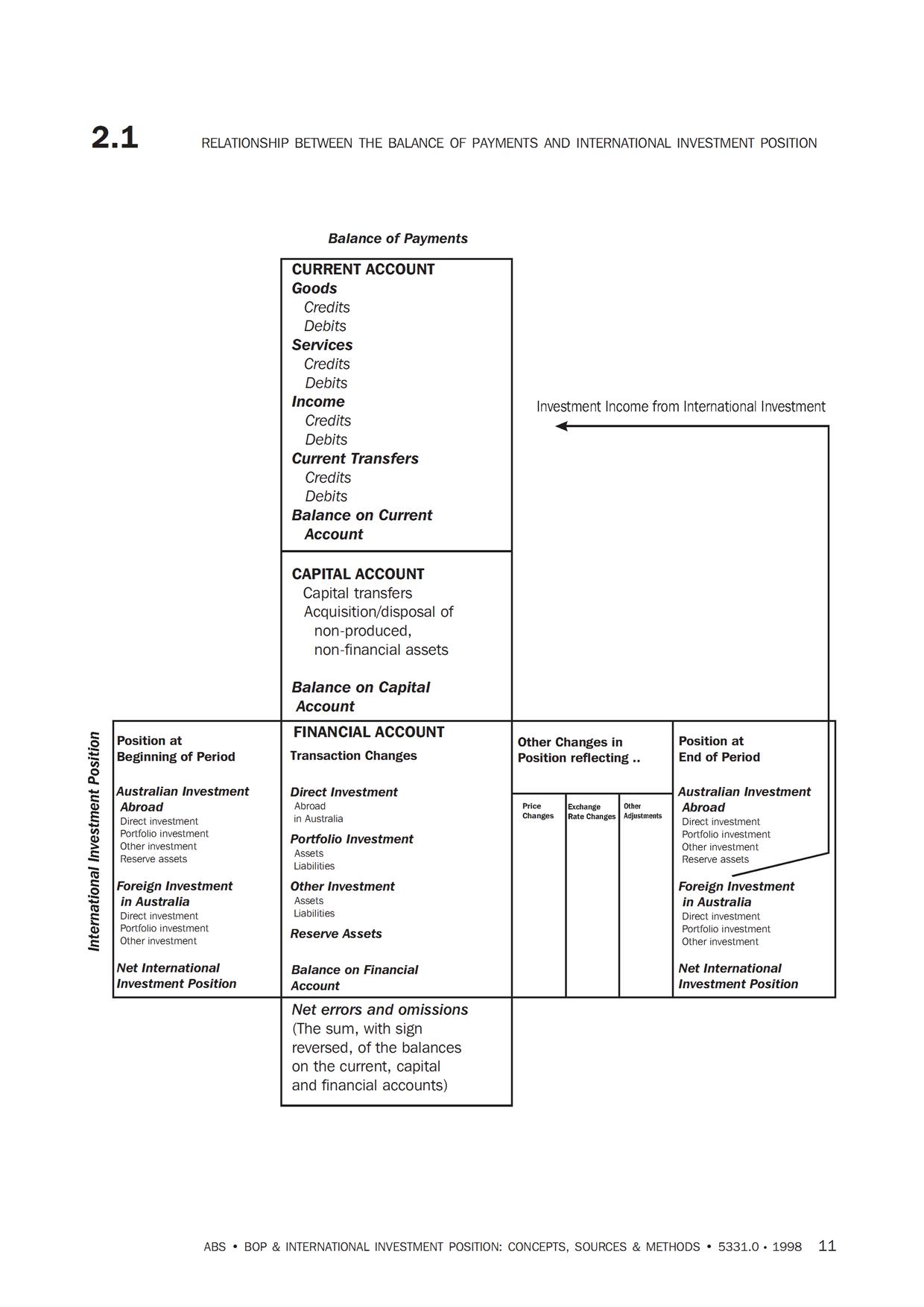

We will discuss this further in many posts and for now here’s a good illustration of how the balance of payments accounts are kept. This is from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ manual Balance of Payments and International Investment Position, Australia, Concepts, Sources and Methods, 1998

So, one starts out with the international investment position and records the transactions in the current account and the financial account. The difference is that the former records income/expenditure flows while the latter records financing flows. The current account includes items such as imports, exports, dividends, interest payments paid to/received from non-residents etc., while the capital account records transactions such as residents’ purchases of assets abroad, increase in liabilities to non-residents and so on. Since debits and credits equal, the balances in the two accounts cancel out. To calculate the international investment position, we add the financial account flows and calculate revaluations to reach the end of period international investment position.

The international investment position records assets and liabilities vis-à-vis the rest of the world. If the difference – the NIIP – is negative, it means the nation is a debtor nation. In the construction above, all transactions between residents and non-residents are recorded – whether in domestic or foreign currency. The numbers are then converted to the domestic currency according to the best rules prescribed by national accountants.

We will look into these in more detail – including all causalities of course – in later posts in this series. Till then, the summary is: imports are purchased on credit.